Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 20

20 March, 2019

CASE II: MSU-SP18-1846 1 (JPC4117533).

Signalment: 15-year-old, intact female, miniature horse, Equus ferus caballus, equine

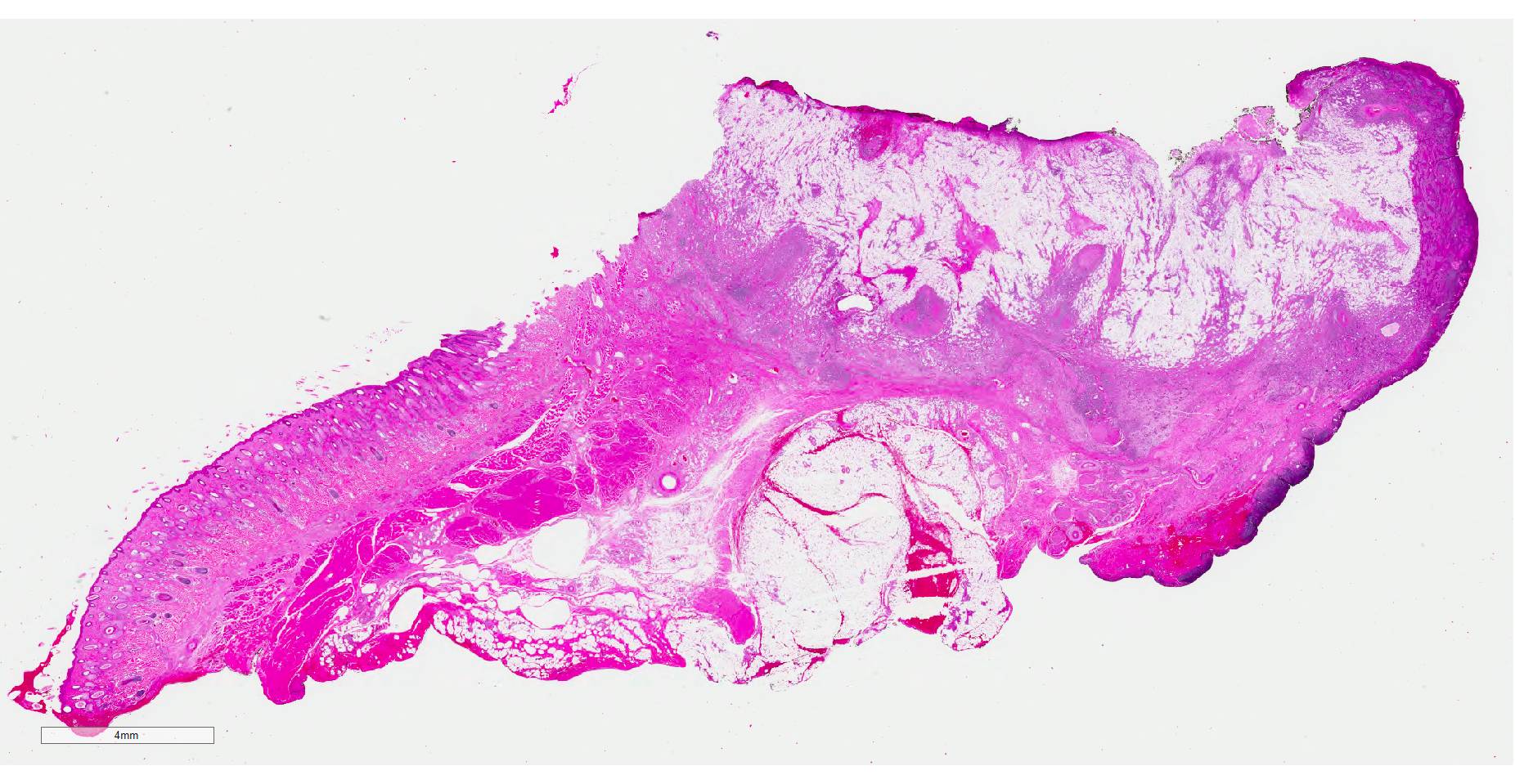

History: This animal had a six month history of irritation of the right eye associated with a non-healing wound on the right lower eyelid. Physical examination revealed a 3cm in diameter, ovoid, ulcerated mass on the right eye lower eyelid that exuded yellow discharge.

Gross Pathology: N/A

Laboratory results: N/A

Microscopic Description:

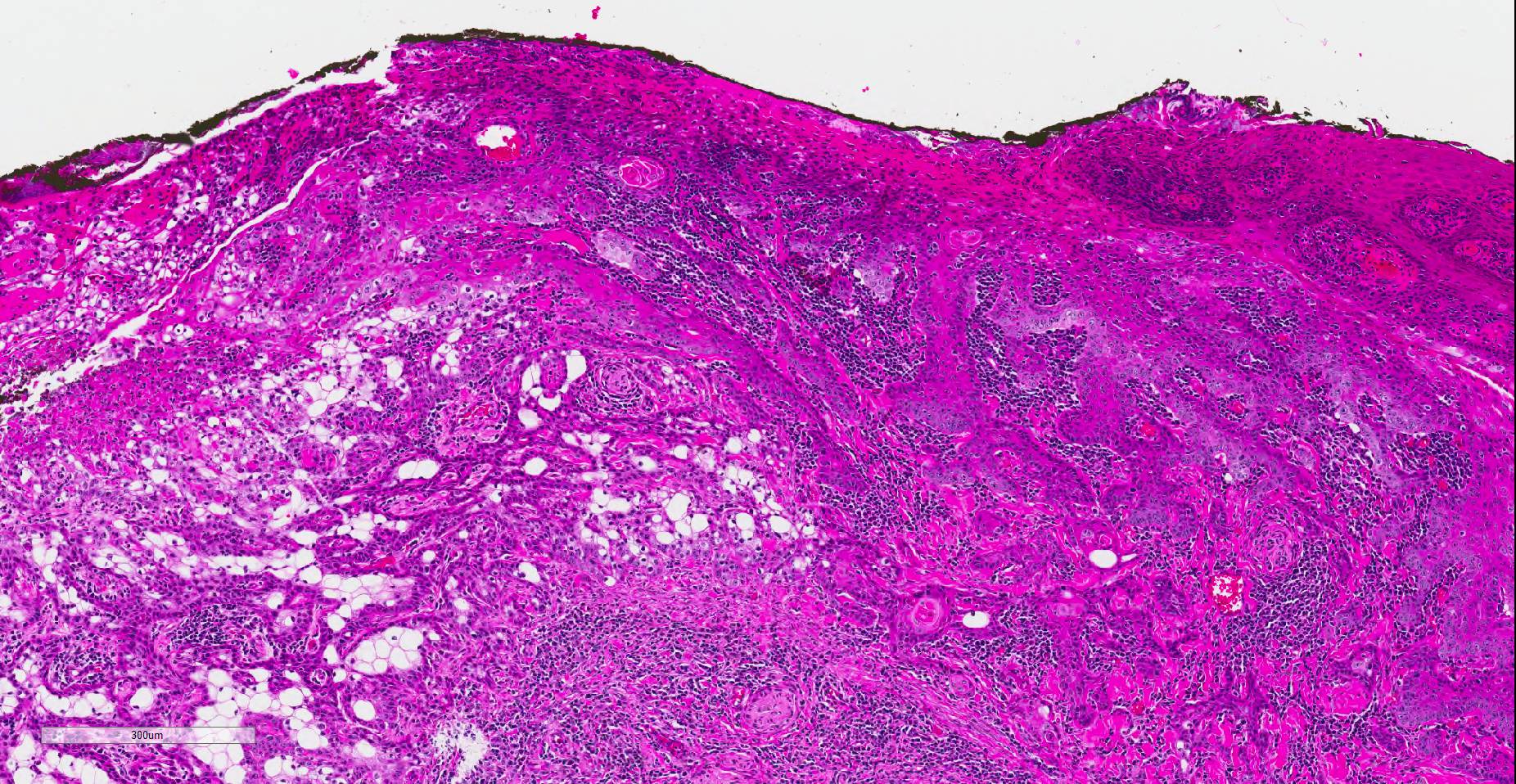

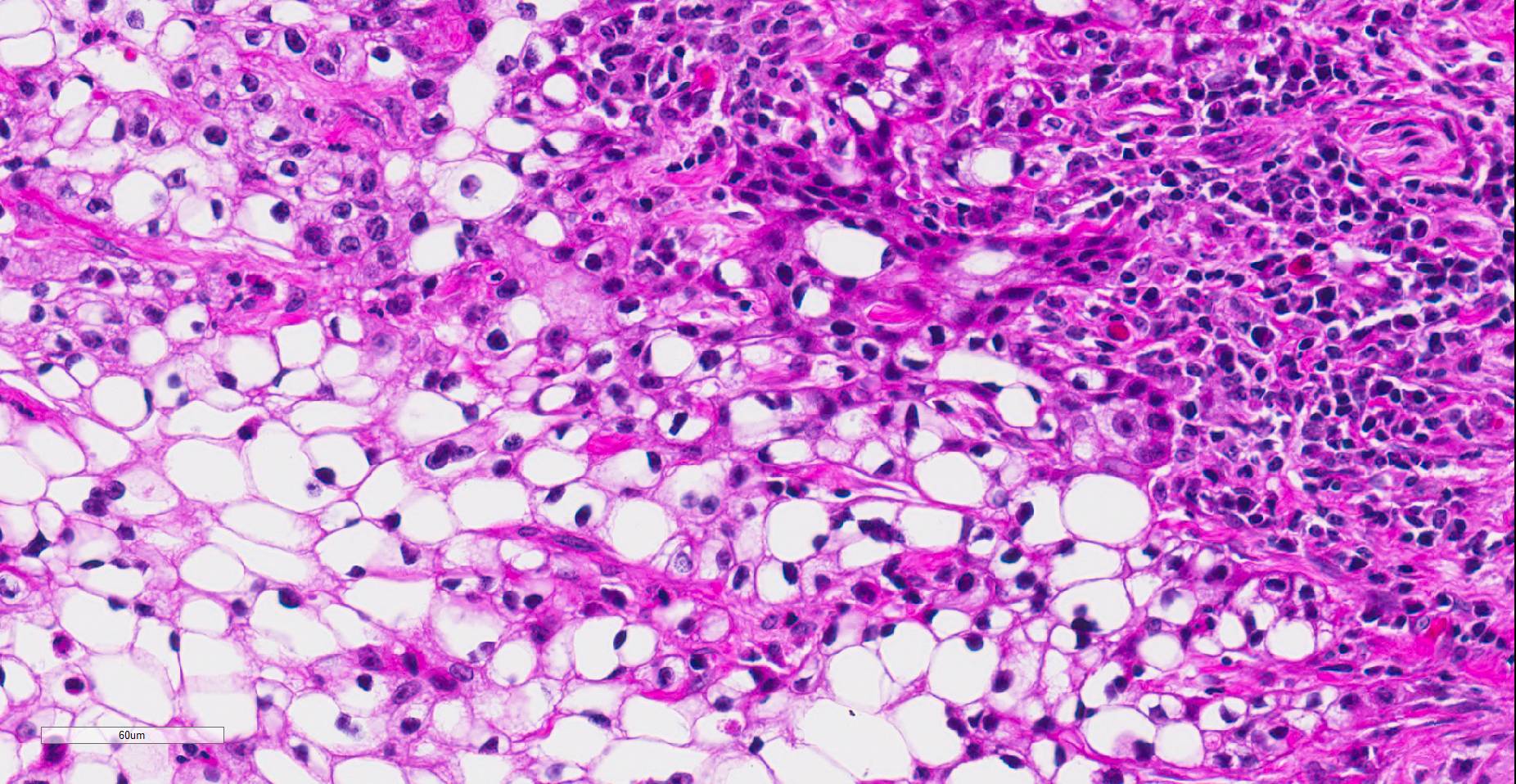

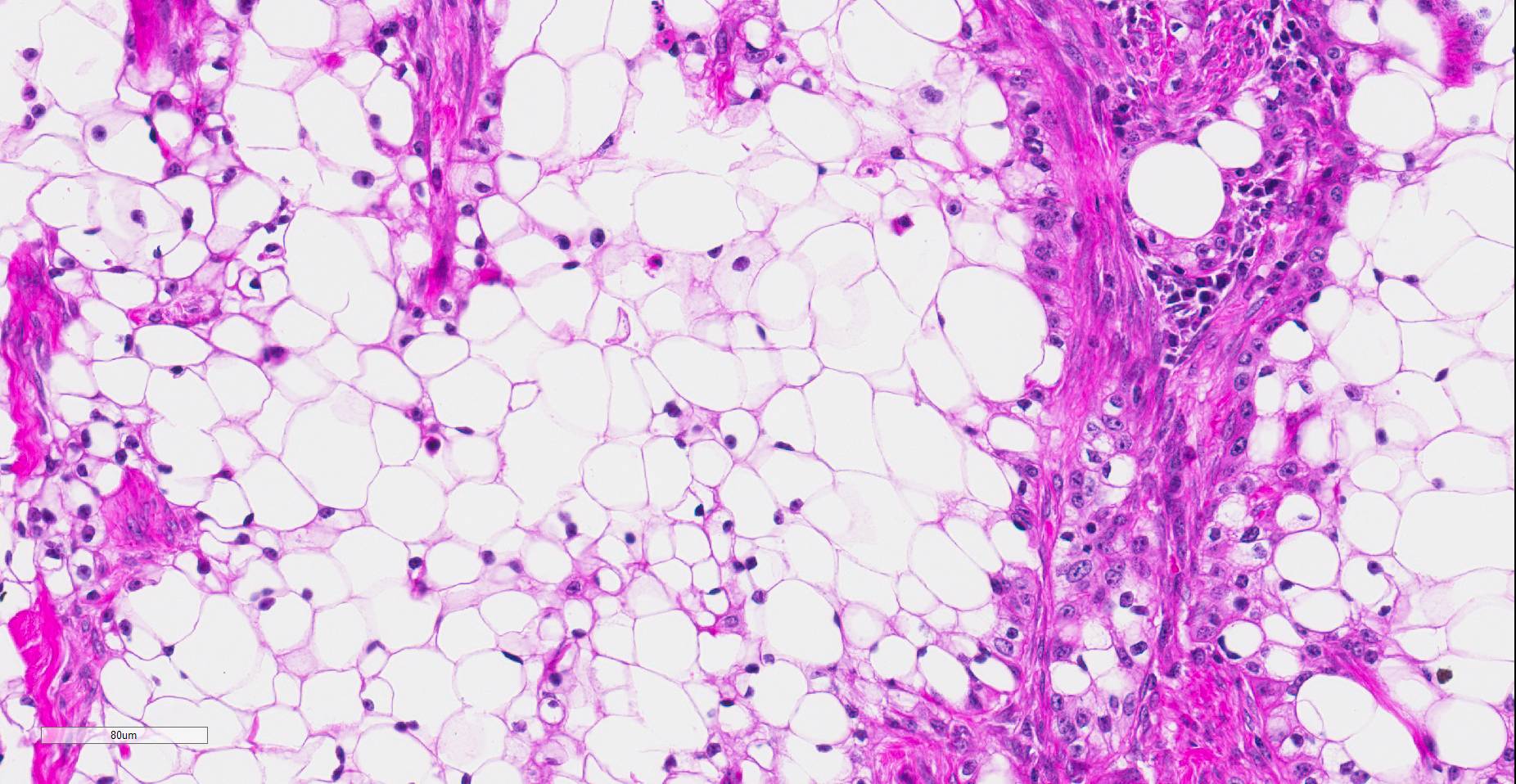

Histopathologic examination revealed a fairly well-demarcated, ulcerated dermal mass composed of neoplastic squamous epithelial cells arranged in anastomosing cords and nests that extended from the surface into the underlying dermis. Neoplastic cords near the surface and along the lateral margins of the mass had multifocal central keratinization. Neoplastic squamous epithelial cells merged with dense sheets of vacuolated polygonal cells towards the center of the mass. The center of the mass was also characterized by nests and cords of neoplastic cells composed of 1-3 outer layers of neoplastic squamous cells that were non-vacuolated and basaloid and rimmed central areas composed entirely of similar large vacuolated polygonal cells that formed sheets in the center of the mass. The non-vacuolated basaloid neoplastic squamous cells were round, contained a small to moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm, and had round to ovoid, finely stippled nuclei that generally contained a single, large, central nucleolus. Anisokaryosis was moderate to marked, depending on the area, and there were occasional binucleated cells. There were 0-2 mitoses per high powered field. The vacuolated polygonal cells often had larger finely stippled nuclei that were peripheralized. Multifocally, nests and cords of neoplastic squamous epithelial cells invaded the underlying dense collagenous connective tissue, focally extended into the underlying skeletal muscle, and often surrounded nerves. In addition, there were multifocal perivascular and perineural inflammatory infiltrates comprised of moderate to large numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells. In some regions, there was sebaceous gland hyperplasia along the surface of the haired skin. The dermis along the lateral margins of the neoplasm also had evidence of solar elastosis. Within the superficial dermis, there were foci of smudged degenerate collagen admixed with tangles of thickened, curled, lightly basophilic fibers that stained black with Verhoeff-van Gieson, consistent with elastin.

Immunohistochemistry for E-cadherin showed strong perimembranous labeling of neoplastic squamous, basaloid and vacuolated polygonal cells. Special staining with oil-red-O, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), and mucicarmine did not reveal positive material within the cytoplasm of vacuolated polygonal cells.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Clear cell squamous cell carcinoma

Contributor’s Comment: While this neoplasm was organized in varying patterns, including extensive sheets of vacuolated cells, there was overt squamous differentiation in several areas. These histologic findings, in conjunction with the immunohistochemical and histochemical staining results, were consistent with a clear cell squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). There was no true tubular or acinar formation and vacuolated polygonal cells lacked cytoplasmic lipid, glycogen, and mucus, further excluding neoplasms of sebaceous or adnexal origin.6-8,10,14,15

To our knowledge, clear cell SCC has not been reported in animals. Variants of squamous cell carcinoma with clear cells have been described in dogs, but have not met the criteria of clear cell squamous cell carcinoma. A signet-ring squamous cell carcinoma was described in the scrotum of one dog, but ultrastructurally clear cells contained intracytoplasmic lipid vacuoles and scattered glycogen.6 The uncommon canine clear cell adnexal carcinomas are also negative for oil red O, but in contrast to our case, positive for PAS.15 Other cutaneous neoplasms with clear cells that have been reported in dogs includes clear cell basal carcinoma, clear cell hidradenocarcinomas, sebaceous carcinomas, balloon cell melanomas, and liposarcomas.7-8,15 None of these entities is characterized by squamous differentiation, and the clear cells in adnexal neoplasms are PAS positive. In horses, clear cell differentiation has only been reported in cutaneous basal cell tumors; however, those tumors lacked the squamous differentiation observed in our case.14

In humans, clear cell SCC is a rare neoplastic entity in the skin also referred to as hydropic SCC. The clear cell appearance is caused by hydropic degeneration of neoplastic squamous cells causing accumulation of intracellular fluid and not glycogen, lipid, or mucin.9,13 Clear cell SCC is divided into three histologic types: keratinizing (type I), nonkeratinizing (type II), and pleomorphic (type III). The keratinizing, or type I, clear cell SCC, is defined by sheets or islands of clear neoplastic cells with peripherally displaced nuclei that are often indistinguishable from adipocytes, as well as some cells that have more vacuolated cytoplasm and resemble sebaceous cells.10 Additionally, there are foci of keratinization or keratin pearl formation. Type II is characterized by anastomosing cords of neoplastic squamous cells with dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates and no keratinization, while type III demonstrates marked pleomorphism, vascular and perineural invasion, foci of squamous differentiation, and microcysts with acantholytic neoplastic cells. In all three types, there is no glycogen or mucin accumulation within clear cells, thus, clear cells are negative for PAS, mucicarmine, and alcian blue stains. AE1/AE3 and cytokeratin 7 have been used to confirm epithelial origin of the neoplastic clear cells.9,11 The case presented here is most consistent with a type I clear cell squamous cell carcinoma.

Squamous cell carcinomas are the most common neoplasm of the equine eye and adnexa.5 SCC of the eyelid typically has an aggressive, locally invasive behavior, and carries a poor prognosis.16 Metastasis is uncommon but may occur late in the course of disease and most often to the regional lymph nodes. We speculate that clear cell SCC will exhibit similar behavior, although this cannot be confirmed due to lack of follow-up in our case. The prognosis of this entity in humans is also unclear due to the scarcity of case reports. Of seven cases of clear cell SCC reported in humans, all but one have occurred on the head or neck of elderly white males who worked outdoors. One case was reported in a dark-skinned adult male who also worked outdoors. Of these reported cases, one patient died of metastatic disease, one died post-operatively, and one had recurrence after 3 months.1,13

In both humans and animals, chronic ultraviolet (UV) light exposure plays an important etiologic role in the development of cutaneous SCC. 3-4,10-11,13 Solar elastosis is a non-neoplastic UV-induced lesion commonly observed in poorly-pigmented skin of horses and humans with or without SCC. It is defined as an accumulation of abnormal elastin in the dermis and is histologically characterized by aggregates of thick interwoven elastic fibers mixed with degenerate collagen within the superficial to mid dermis as observed in our case. The pathogenesis of elastin accumulation is unclear, but is often seen in poorly pigmented or non-pigmented skin with chronic UV exposure, or in conjunction with other solar induced changes such as solar (actinic) keratosis, epidermal plaques, and SCC. In horses, solar-associated SCC has been reported in the conjunctiva, eyelid, and vulvar epithelium, and is morphologically similar to solar-induced SCC in humans, often exhibiting solar elastosis within or adjacent to the neoplasm.3 Chronic UV-exposure evidenced by solar elastosis has been observed in human cases of clear cell SCC, and is hypothesized to play a role in the development of the disease.13 The solar elastosis observed in our case parallels that of human clear cell SCC, and suggests that chronic UV exposure may play an etiologic role in the development of clear cell SCC in horses as well.

Contributing Institution:

Michigan State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory and Department of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation, College of Veterinary Medicine, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA https://dcpah.msu.edu/

JPC Diagnosis: Haired skin, eyelid: Squamous cell carcinoma, clear cell variant.

JPC Comment: This is a unique neoplasm in the experience of the JPC Vet Path Service. Since the original submission of this case, it has been published as a case report in the Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation.17

This case was reviewed by human subspecialty pathologists at the JPC, who rendered the following consultation – “Interesting case. Based on morphology, we believe a lot of the clear cells are cytologically bland and there are areas of definite tubular differentiation, favoring a malignant clear cell hidradenoma. Additional myoepithelial stains would favor an adnexal origin rather than squamous cell carcinoma. Less likely would be a metastatic clear cell carcinoma such as metastatic renal cell carcinoma18. This is not favored based on morphology, but there seems to be co-expression of vimentin and cytokeratin in the section that we reviewed.”

Hidradenoma, a term far more commonly used in human rather than veterinary pathology, generally refers to neoplasms of eccrine sweat glands, which the moderator pointed out are not present in the horse (except in the portion of the hoof known as the frog). More recent investigations into the etiology of hidradenomas in humans have postulated potential origins from apocrine sweat glands as well.)

The consensus of the attendees is that while there is a focus of tubular differentiation of neoplastic cells at the deep margin, the predominant form of differentiation is toward a squamous cell morphology, and agree with the contributor’s diagnosis in this case. In addition, areas of solar elastosis were noted in the superficial dermis, lending credence to the contributor’s suggestion that is represents a neoplasm induced by chronic UV exposure.

References:

- Al-Arashi MY, Byers HR. Cutaneous clear cell carcinoma in situ: clinical, histological and immunohistochemical characterization. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:226-233.

- Berk DR, Lennerz JK, Bayliss SJ, Lind A, White FV, Kane AA. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma on the scalp of a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002; 24:452-453.

- Campbell GA, Gross TL, Adams R. Solar elastosis with squamous cell carcinoma in two horses. Vet Pathol.1987;24:463-464.

- Corbalán-Vélez R, Ruiz-Macia JA, Brufau C, López-Lozano JM, Martínez-Barba E, Carapeto FJ. Clear cells in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:307-316.

- Dugan SJ, Curtis CR, Roberts SM, Severin GA. Epidemiologic study of ocular/adnexal squamous cell carcinoma in horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991; 198:251–256.

- Espinosa de los Monteros A, Aguirre-Sanceledonio M, Ramírez GA, Castro P, Rodríguez F. Signet-ring squamous cell carcinoma in a dog. Vet Rec. 2003;153:90-92.

- Goldschmidt MH, Dunstan RW, Stannard AA. Histological classification of epithelial and melanocytic tumors of domestic animals. In: Schulman FY, ed. World Health Organization International Histological Classification of Tumors of Domestic Animals. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology 1998.

- Jabara AG, Finnie JW. Four cases of clear-cell hidradenocarcinomas in dogs. J Comp Pathol .1978;88:525-532.

- Kuo T. Clear cell carcinoma of the skin. A variant of the squamous cell carcinoma that simulates sebaceous carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1980;4:573–83.

- Lawal AO, Adisa AO, Olajide MA, Olusanya AA. Clear cell variant of squamous cell carcinoma of skin: A report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2013;17:110-112.

- Rashid A, Jakobiec FA, Mandeville JT. Squamous cell carcinoma with clear-cell features of the palpebral conjunctiva. JAMA Opthalmol. 2014;132:1019-1021.

- Montiani-Ferreira F, Kiupel M, Muzolon P, Truppel J. Corneal squamous cell carcinoma in a dog: a case report. Vet Ophthalmol. 2008;11:269-272.

- Rinker MH, Fenske NA, Scalf LA, Glass LF. Histologic variants of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer Control. 2001;8:354-363.

- Schuh JCL, Valentine BA. Equine basal cell tumors. Vet Pathol 1987;24:44-49.

- Schulman FY, Lipscomb TP, Atkin TJ. Canine cutaneous clear cell adnexal carcinoma: histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and biologic behavior of 26 cases. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2005;17:403-411.

- Schwink K. Factors influencing morbidity and outcome of equine ocular squamous cell carcinoma. Equine Vet J. 1987;19:198–200.

- Stein L, Sledge D, Smedley R, Kiupel M, Thaiwong T. Squamous cell carcinoma with clear cell differentiation in an equine eyelid. J. Vet Diagn Invest. 2019; 259-262.

- Williams JC, Heaney JA. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma presenting as a skin nodule: case report and review of the literature. J Urol. 1994;152:2094–2095.