WSC 22-23

Conference 2

CASE II: 17-15645 (JPC 4117035)

Signalment:

11-yr-old, F/S, Canine, Labrador cross

History:

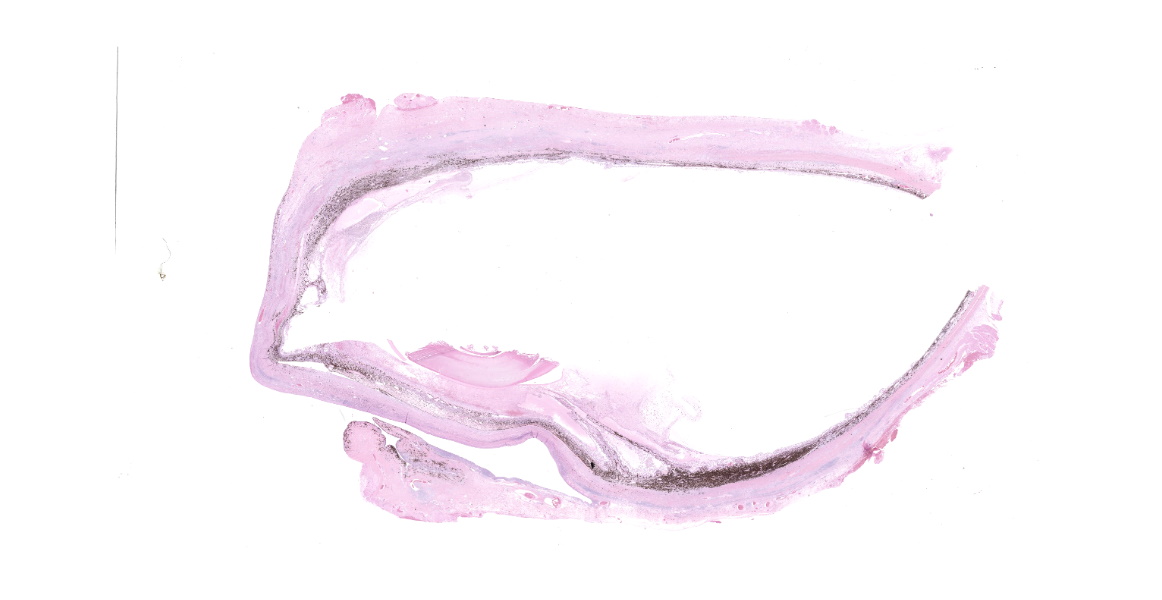

The dog was diagnosed with suspected immune-mediated keratitis 2 months prior. The dog did very well with treatment for 1.5 months but developed prominent thickening of the scleral wall and infiltrative keratitis laterally. A computed topography (CT) scan also showed severe thickening of the scleral wall without extraorbital irregularities. Due to pain, blindness and now a failure to respond to treatment, enucleation was performed.

Gross Pathology:

The right eye was submitted, and no obvious mass was observed in parasagittal bisections.

Laboratory Results:

No laboratory findings reported.

Microscopic Description:

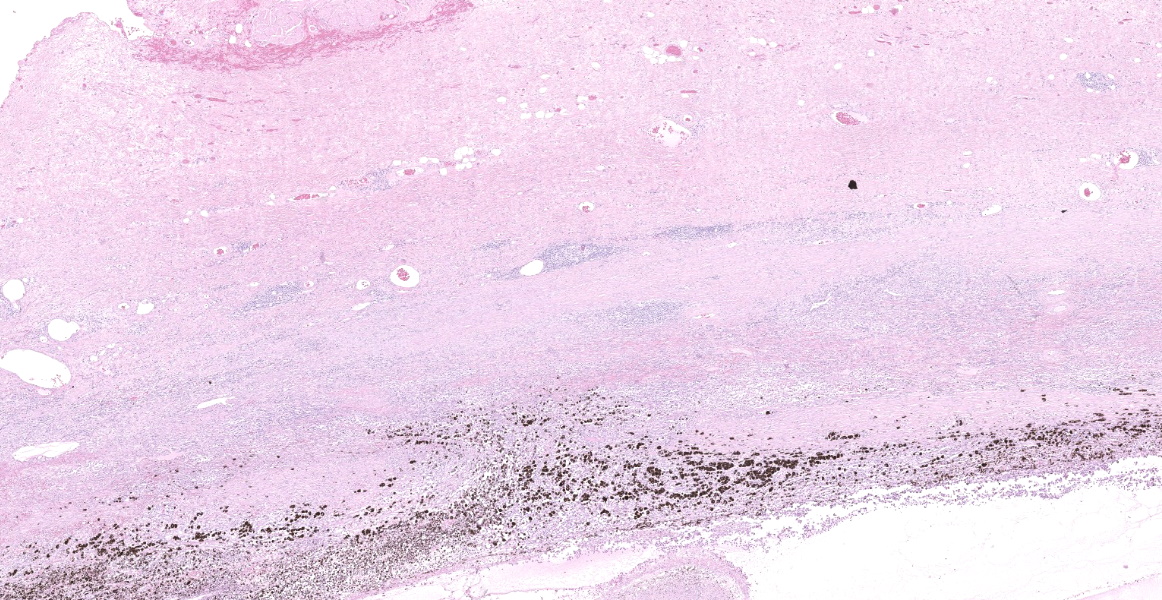

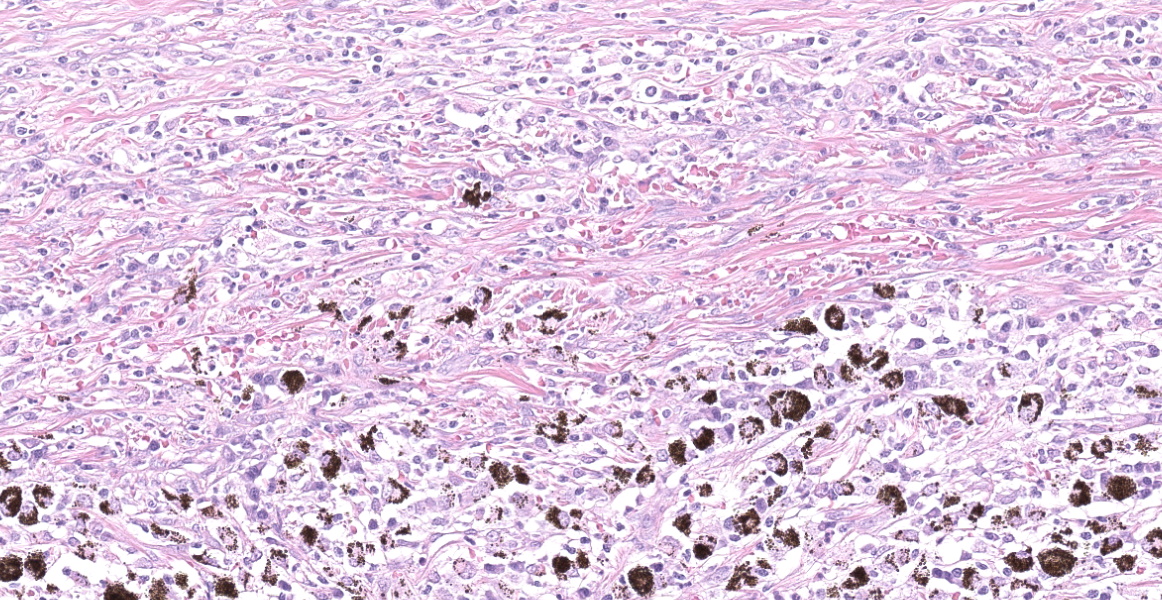

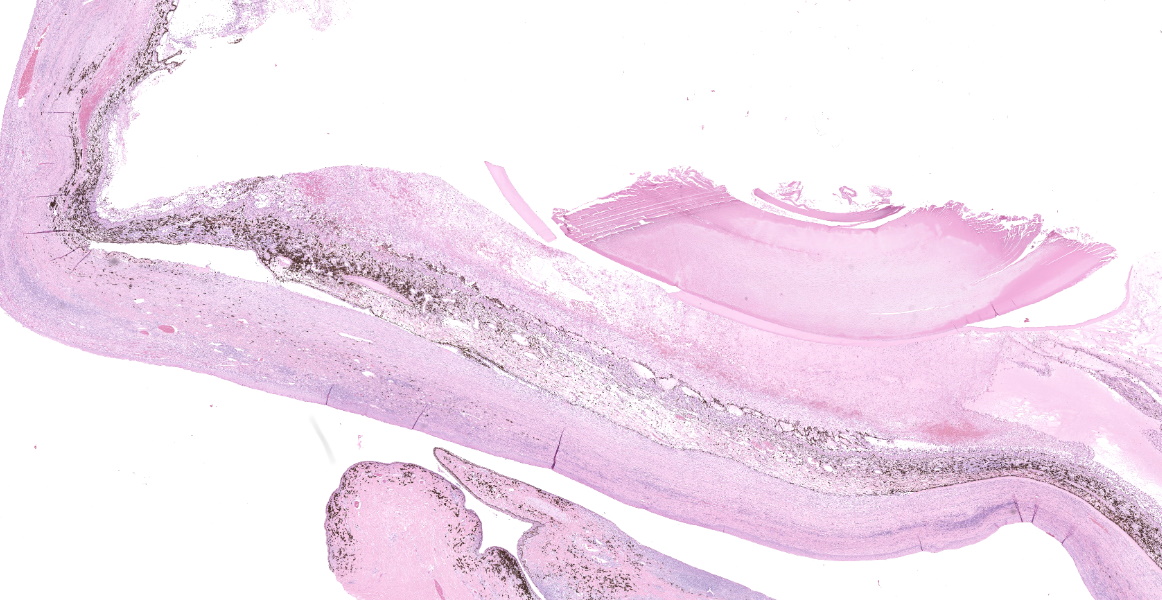

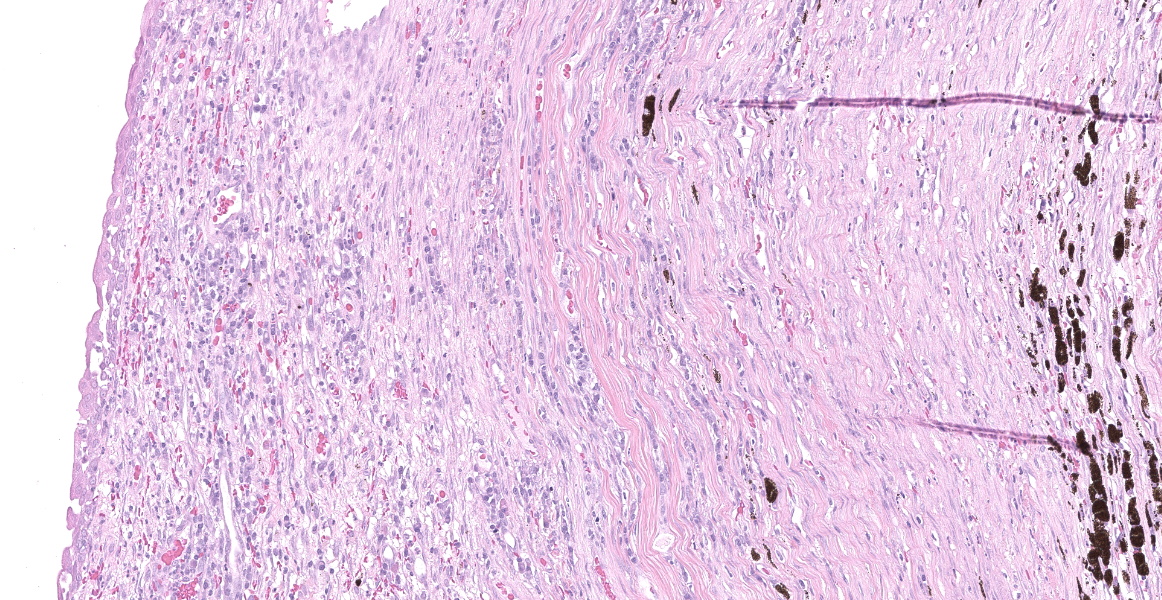

Right eye: The corneal stroma is infiltrated by large numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells with fewer neutrophils, small amounts of extracellular melanin pigment and scattered melanophages. The stroma has significant corneal neovascularization, and at the limbus, some corneal epithelial cells have intraepithelial melanin pigment. The remainder of the corneal epithelium is irregularly hyperplastic or eroded, and there are small numbers of interepithelial neutrophils and scattered apoptotic epithelial cells. The sclera is markedly thickened and broadly infiltrated by abundant macrophages, neutrophils, plasma cells, and lymphocytes accompanied by small amounts of necrotic cellular debris and many, large lymphoid aggregates. The scleral collagen is separated in areas (collagenolysis). The basement membrane separating the choroid and sclera is often obscured by inflammation, which extends into the choroid and vitreous chamber, and aggregates of melanocytes infiltrate the sclera. Multifocal scleral vessel walls are infiltrated by the inflammation (vasculitis), and one vessel is filled with organized fibrin (thrombus). The retina is detached, but obvious tomb-stoning of underlying pigmented epithelium is not apparent (possible artifactual retinal detachment). In addition to abundant large foamy macrophages and neutrophils within the vitreous chamber, there are also aggregates of erythrocytes, fibrin and flocculent eosinophilic material. The iris and ciliary body are expanded by similar inflammation and the anterior iris epithelium is covered by a 2-5 cell layer thick fibrovascular membrane (pre-iridal fibrovascular membrane), which is adhered to the cornea (anterior synechia) and spreads across the entirety of Decemet's membrane. Additionally, the posterior iris is adhered to the lens (posterior synechia; lens is not within provided sections). The iridocorneal filtration angle and uveal trabecular meshwork are unapparent due to the anterior synechiae, and infiltration by inflammatory cells. The conjunctival propria has multifocal to coalescing aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells, generally superficial and peri-adnexal.

Special stains: No organisms were detected in serial sections stained with Fite's acid fast or Grocott's methenamine silver stains.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

- Scleritis, histiocytic, neutrophilic, lymphoplasmacytic and necrotizing, chronic, severe, with vasculitis, choroiditis, endophthalmitis, anterior uveitis, anterior and posterior synechiae, and closure of the iridocorneal filtration angle

- Keratitis and conjunctivitis, lymphoplasmacytic, chronic, moderate, with corneal erosion and neovascularization

Contributor's Comment:

The histologic features are compatible with granulomatous/necrotizing scleritis. Not all submitted slides show all the histologic changes (e.g. retina and lens are absent in most slides), and the audience is urged to focus on the scleral, corneal and uveal changes.

Idiopathic necrotizing/ granulomatous scleritis is a condition manifested as a bilateral, progressive, inflammatory disease of the sclera and cornea that induces significant uveitis, most commonly in dogs, but has been diagnosed in a cat and 2 birds.4,5 Grossly, the affected area of sclera is usually thickened and solid white, representing the granulomatous infiltrate. The histologic lesions of granulomatous scleritis are characterized by vasculitis, collagen degeneration/collagenolysis, granulomatous inflammation (histiocytes/tissue macrophages) and perivascular lymphoplasmacytic aggregation.2,4,5 There may be a suppurative component, or in chronic scleritis, a lymphoplasmacytic component may predominate. Less commonly, the sclera may be thin and have dramatic staphylomas associated with a more lymphocyte-rich infiltrate. Retinal detachment is a possible sequela to granulomatous/necrotizing scleritis. A diagnosis of scleritis in one eye implies that the second eye is at risk of developing scleritis. Idiopathic canine necrotizing scleritis shares similar histopathologic features with non-necrotizing scleritis (trauma or foreign-body related) and episcleritis, but these diseases are generally unilateral.5

In humans, granulomatous scleritis has been associated with other autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener's granulomatosis, inflammatory bowel disease and Reiter's syndrome, but this has not been a consistent feature of reported canine cases.2,5,7,10-13 In humans, necrotizing scleritis is regarded as a type III hypersensitivity reaction (immune complexes), as well as combined with a type IV hypersensitivity.1,3,6 The condition in dogs is thought to be immune-mediated, and one study demonstrated IgG deposition within blood vessel walls in one dog, suggestive of

an immune-complex component (type III hypersensitivity).2 A primary type IV hypersensitivity was proposed, in addition to an underlying type III hypersensitivity, based on vascular/perivascular granulomatous to lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. This study described a prominent population of T lymphocytes, and proposed that CD4+ T lymphocytes are responsible for the tissue destruction in this disease. However, another study described a mixed population of lymphocytes (B lymphocytes predominated), which may also support the type III sensitivity involvement theory.4 Response to medical therapy with corticosteroids (topical, systemic) or other immunomodulators such as azathioprine have been reported and also supports an immune-mediated etiology, but relapses and complications resulting in blindness occur frequently. Since little is known about the pathogenesis of idiopathic necrotizing scleritis in dogs, and there are few, somewhat contrasting reports in the literature, comparing the disease to human scleritis may not be appropriate.

Contributing Institution:

Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic Lab

College of Veterinary Medicine, Washington State University

JPC Diagnosis:

- Eye: Scleritis, collagenolytic, lymphoplasmacytic, chronic, diffuse, severe, with keratitis, panuveitis, anterior synechia, fibrovascular membranes, and hyphema.

- Conjunctiva: Conjunctivitis and dacryoadenitis, lymphoplasmacytic, chronic, multifocal, moderate.

JPC Comment:

This case provides a classic example of the relatively rare condition necrotizing granulomatous scleritis, and the contributor succinctly describes this condition in veterinary species as well as similar diseases in humans. Two differential diagnoses that may be considered during clinical and histopathologic examination are episcleritis and non-necrotizing granulomatous scleritis. Additional differential diagnoses for granulomatous disease include bacterial, acid-fast, and fungal infections, which were not observed on special stains in this case.

Episcleritis can occur secondary to severe intraocular or systemic disease, or may be a primary condition, such as in nodular granulomatous episcleritis (NGE), an inflammatory disease affecting the episcleral and adjacent conjunctiva.6 NGE is more common and has a slower onset than necrotizing granulomatous scleritis. Single or multiple nonpainful elevated fleshy masses develop near the limbus or nictitating membrane and may extend into the adjacent cornea. A recent report described three cases of atypical NGE where the inflammatory infiltrate was limited to the corneal stroma and did not extend into the epsiclera or conjunctiva; the histologic appearance otherwise was consistent with NGE.9 Severe cases of NGE may cause exophthalmos.14 While both nodular granulomatous episcleritis and necrotizing granulomatous scleritis feature histiocytes admixed with lymphocytes and plasma cells, the episcleritis nodules are discrete (compared to the invasive nature of necrotizing scleritis) and lack collagenolysis.

Non-necrotizing granulomatous scleritis also lacks the collagenolysis and perivascular necrosis seen with the necrotizing version of the disease. Additionally, chronic cases may feature fibrosis or formation of cystic spaces, and in general, it is generally milder than its necrotizing counterpart.8,14 Otherwise, non-necrotizing granulomatous scleritis causes a similar spectrum of clinical signs, including ocular pain, and can infiltrate to other structures in the eye, causing keratitis, uveitis, and choroiditis, as seen in this case.

References:

- Akpek EK. Necrotizing Scleritis: Diagnosis and therapy. The Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation. 1994; I(3). Accessed May 25, 2018. https://uveitis.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/necrotizing_scleritis_diagnosis_therapy.pdf

- Day MJ, Mould JR, Carter WJ. An immunohistochemical investigation of canine idiopathic granulomatous scleritis. Vet Ophthalmol. 2008;11(1):11-7.

- De la Maza MS, Tauber J, Foster CS. Immunological considerations of the sclera. In: The sclera. New York, NY: Springer; 2012: 33-58.

- Denk N, Sandmeyer LS, Lim CC, Bauer BS, Grahn BH. A retrospective study of the clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical manifestations of 5 dogs originally diagnosed histologically as necrotizing scleritis. Vet Ophthalmol. 2012;15(2):102-9.

- Dubielzig RR, Ketring K, McLellan GJ, and Albert DM. Diseases of the Cornea and Sclera. In: Veterinary Ocular Pathology: a comparative review. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010: 201-243.

- Gan, YK, Ahmad SS, Alexander SM, Samsudin A. Acute anterior necrotizing scleritis: A case report. J Acute Dis. 2016:5(5): 439-41.

- Ghanchi FD, Rembacken BJ. Inflammatory bowel disease and the eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48(6):663-676.

- Grahn BH, Sandmeyer LS. Canine Episcleritis, Nodular Episclerokeratitis, Scleritis, and Necrotic Scleritis. Vet Clin Small Anim. 2008; 38:291-308.

- Hamzianpour N, Heinrich C, Gareth Jones R, et al. Clinical and pathological findings in three dogs with a corneocentric presentation of nodular granulomatous episcleritis. Vet Ophth. 2019: 1-9.

- Harper SL, Letko E, Samson CM, Zafirakis P, et al. Wegener's granulomatosis: the relationship between ocular and systemic disease. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(5):1025-32.

- Heiligenhaus A, Dutt JE, Foster CS. Histology and immunopathology of systemic lupus erythematosus affecting the conjunctiva. Eye (Lond).1996; 10(4):425-32.

- Kiss S, Letko E, Qamruddin S, Baltatzis S, Foster CS. Long-term progression, prognosis, and treatment of patients with recurrent ocular manifestations of Reiter's syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(9):1764-9.

- Reddy SC, Rao UR. Ocular complications of adult rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 1996;16(2):49-52.

- Whitley RD, Hamor RE. Diseases and Surgery of the Canine Cornea and Sclera. In: Gelatt KN, ed. Veterinary Ophthalmology. Vol 1. 6th Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell; 2021.1153-1155.

- Wilcock BP, Njaa BL. Special Senses. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016: 407-508.