Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

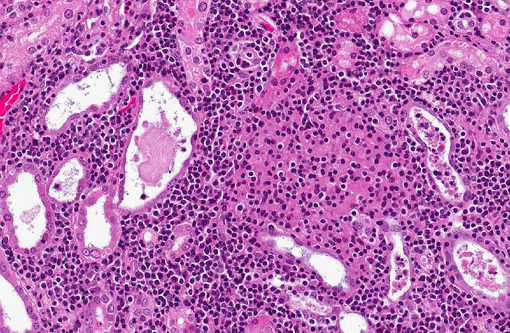

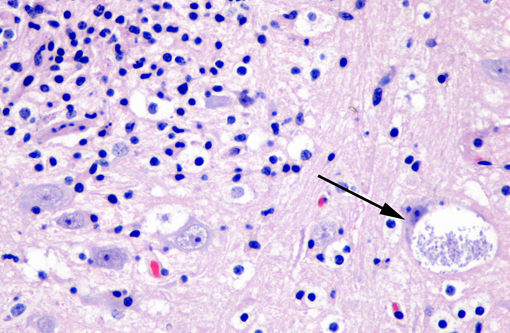

Affecting the gray and white matter of the cerebrum and the cerebellum (slide not provided), there are scattered, nodular infiltrates of moderate numbers of macrophages (which contain 1.5 x 3 μm refractile spores in their cytoplasm) and activated microglia, few lymphocytes and plasma cells, and rare neutrophils together with small amounts of necrotic debris. Rarely there are 10-100 μm in diameter cysts which contain numerous, 1.5 x 3 μm refractile spores; these cysts are present both in areas of inflammation and in areas free of inflammation. The leptomeninges in many areas are moderately expanded by a similar inflammatory infiltrate. Vessels are lined by reactive endothelium and there is a small amount of hemorrhage in the leptomeninges.

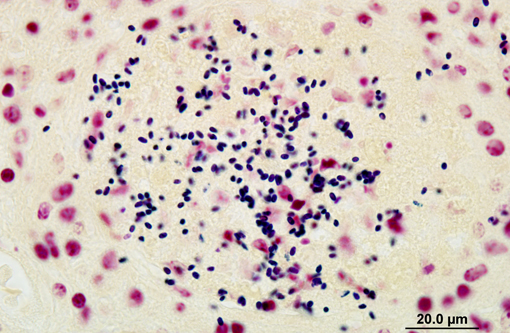

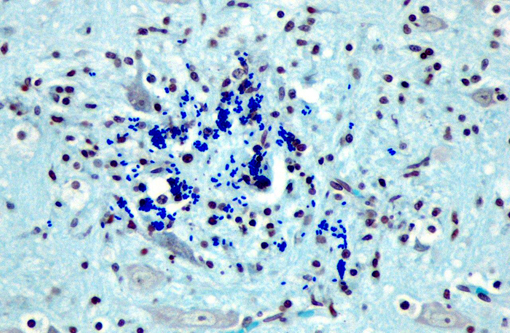

The spores in the kidney and the brain stained gram positive with the Brown and Brenn's gram stain and faintly acid-fast-positive with Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast stain.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

A sample of frozen kidney was positive by PCR testing for Encephalitozoon cuniculi.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Encephalitozoon cuniculi is a microscopic parasite that belongs to the phylum Microspora, which encompasses obligate intracellular, spore-forming, single-celled parasites with a direct life cycle.(5,9) Microsporidia are characterized by a severe reduction, or even absence, of cellular components typical of eukaryotes such as mitochondria, Golgi apparatus and flagella. This simplistic cellular organization has made it difficult to infer the evolutionary relationship of Microsporidia to other eukaryotes. It is now widely acknowledged that features of Microsporidia previously recognized as primitive are instead highly derived adaptations to their obligate parasitic lifestyle.2 Microsporidia were initially thought to be protozoa but subsequent molecular biological evidence suggests that they are more closely related to fungi than protozoa.(10) These findings include the presence of a particular mitochondrial heat shock protein more closely related to that of fungi, alpha- and beta-tubulins that are closely related in composition to those of fungi, and the presence of chitin and trehalose, which are typical components of fungi.(6,10)

Encephalitozoon cuniculi infections have been reported in many mammalian species, e.g. rabbits, SCID mice, guinea pigs, alpacas, neonatal foxes, neonatal dogs, and immune compromised people. Severe disease is rare except in immune compromised mammals.(5,7,10,11) Three strains have been identified: strain I was found in rabbits and humans, strain II in rodents and blue foxes, and strain III in dogs and humans. Identification of strains in humans and animals suggest possible zoonotic transmission. Although strain III of E. cuniculi is found in humans and dogs, no direct evidence suggests that dogs can transmit the disease to humans.(3)

Encephalitozoon cuniculi transmission occurs through ingestion, by inhalation of contaminated urine or feces shed by infected hosts, transplacentally, and rarely by penetration across injured epithelium.(8,10) Microsporidia extrude a polar tube and inject the infective sporoplasm into the host cell in response to the appropriate environmental stimuli from the host. Subsequently, development proceeds by two processes, i.e. merogony and sporogony. During merogony the sporoplasm divides and generates numerous proliferative forms called meronts. Sporogony produces intermediate stages known as sporonts, which produce sporoblasts that will mature into spores and eventually be released into extracellular space.(12)

In naturally infected rabbits, E. cuniculi infections are often subclinical. Occasionally infected rabbits will display neurologic signs of ataxia, opisthotonos, torticollis, hyperaesthesia, or paralysis.(4) This is especially true in young rabbits. Dwarf rabbits are also especially susceptible.(10) Focal, irregular, depressed areas in the renal cortex can be seen in chronically infected rabbits; however, gross lesions are usually absent in infected rabbits.(4) The parasite is able to infect a large variety of cell types, such as neurons, epithelial cells of ependyma and choroid plexus, renal tubular epithelium, endothelium and macrophages.(10) Characteristic foci of granulomatous inflammation and organisms are observed in brain, kidney, lung, adrenal gland, and liver.(5) Histologically, multifocal nonsuppurative meningoencephalitis with astrogliosis and perivascular lymphocytic infiltration and focal to segmental lymphocytic-plasmacytic interstitial nephritis with variable amounts of fibrosis are reported. Early lesions in the kidney display focal to segmental granulomatous interstitial nephritis with degenerated epithelial cells and mononuclear cell infiltration. Lesions minimally involve glomeruli. In the lung, focal to diffuse interstitial pneumonia with mononuclear cell infiltration may occur. Hepatic lesions are characterized by a focal granulomatous inflammatory response with periportal lymphocytic infiltration. Multifocal lymphocytic infiltrates may also occur in the myocardium. With the Gram stain parasites are seen as gram-positive, 1.3-1.5 μm, rod-shaped organisms in the intracellular parasitophorous vacuoles of cells. Encephalitozoonosis in rabbits should be differentiated from infection by Pasteurella multocida, Listeria monocytogenes, and Toxoplasma gondii.(8,10) Electron microscopy can reveal the organisms in parasitophorous vacuoles as well as the distinctive polar filaments.(3)

The incidence of encephalitozoonosis is on the decline in many areas, particularly in well-managed rabbitries. Regular serological testing will readily identify infected animals. Since seroconversion precedes renal shedding, infected animals can be identified before they are shedding organisms in the urine.(8)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

References:

2. Corradi N, Keeling PJ. Microsporidia: a journey through radical taxonomical revisions. Fungal Biology Reviews. 2009;23:1-8.

3. Didier PJ, Snowden K, Alvarez X, Didier ES. Microsporidiosis. In: Green CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2006:711-716.

4. Flatt RE, Jackson SJ. Renal nosematosis in young rabbits. Vet Pathol. 1970;7(6):492497.

5. Fuentealba IC, Mahoney NT, Shadduck JA, Harvill J, Wicher V, Wicher K. Hepatic lesions in rabbits infected with Encephalitozoon cuniculi administered per rectum. Vet Pathol. 1992;29(6):536-540.

6. Keeling PJ, McFadden GI. Origins of microsporidia. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6(1):1923.

7. Lallo MA, Calabria P, Milanelo L. Encephalitozoon and Enterocytozoon (Microsporidia) spores in stool from pigeons and exotic birds: microsporidia spores in birds. Vet Parasitol. 2012;190(3-4):418-22.

8. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Rabbit. In: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing; 2007:290-294.

9. Szabo JR, Shadduck JA. Experiemental encephalitozoonosis in neonatal dogs. Vet Pathol. 1987;24(2):99-108.

10. Wasson K, Peper RL. Mammalian microsporidiosis. Vet Pathol. 2000;37(2):13-28.

11. Webster JD, Miller MA, Vemulapalli R. Encephalitozoon cuniculi-associated placentitis and perinatal death in an alpaca (Lama pacos). Vet Pathol. 2008;45(2):255258.

12. Weidner E. Ultrastructural study of microsporidian invasion into cells. Z Parasitenkd. 1972;40(3):227242.