CASE 3: ND18-48 (4122555-00)

Signalment: 1-½ year old, Chat-Cre transgenic, female, Long Evans rat (Rattus norvegicus)

History: This was a rat used for training research staff on proper rat handling technique. The animal presented with ataxia, tachypnea, and a ruffled coat. There was no history of prior clinical abnormalities.

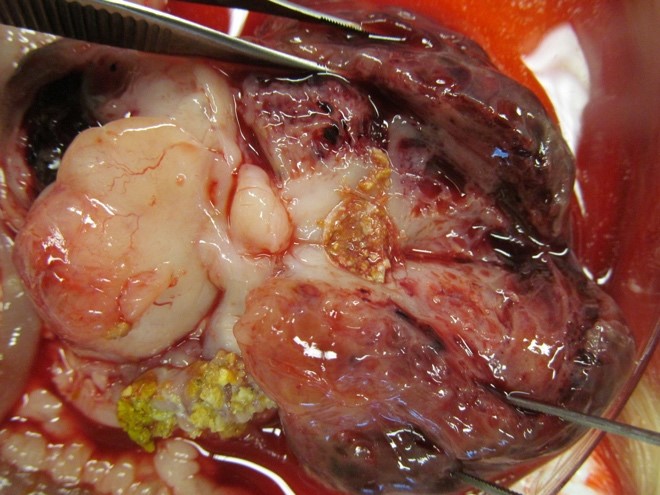

Gross Pathology:

On necropsy, the abdominal cavity was filled and expanded by 2 large coalescing adherent masses: The cranial mass was more solid, firm and tan measuring 4 cm x 2 cm x 2 cm while the second caudal mass measuring 4 cm x 5 cm x 2 cm was tan-white, moderate soft with multiple variable size cysts filled with brown fluid. The tan solid mass was found to be associated and firmly adherent to the lesser curvature of the stomach. There were small amounts of serosanguineous abdominal fluid. The masses compressed and displaced the diaphragm cranially. There was adhesion of the abdominal mass to the spleen.

Laboratory results:

Not pursued.

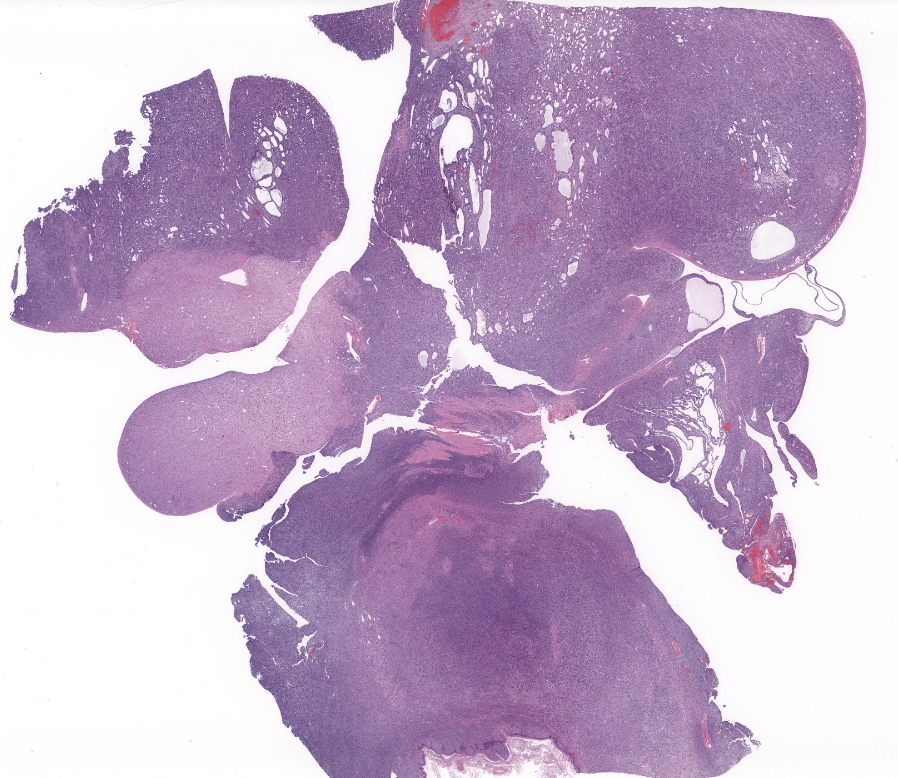

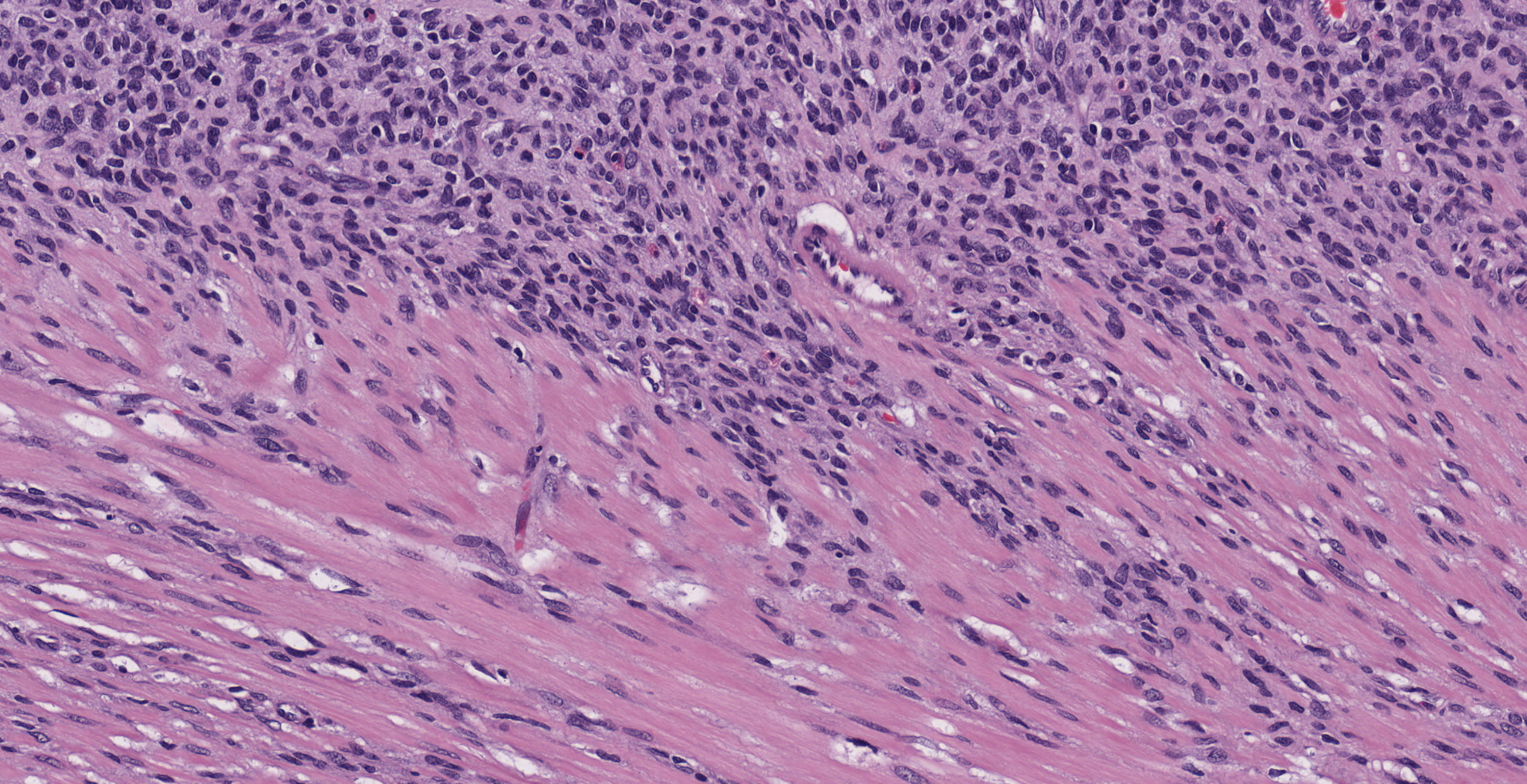

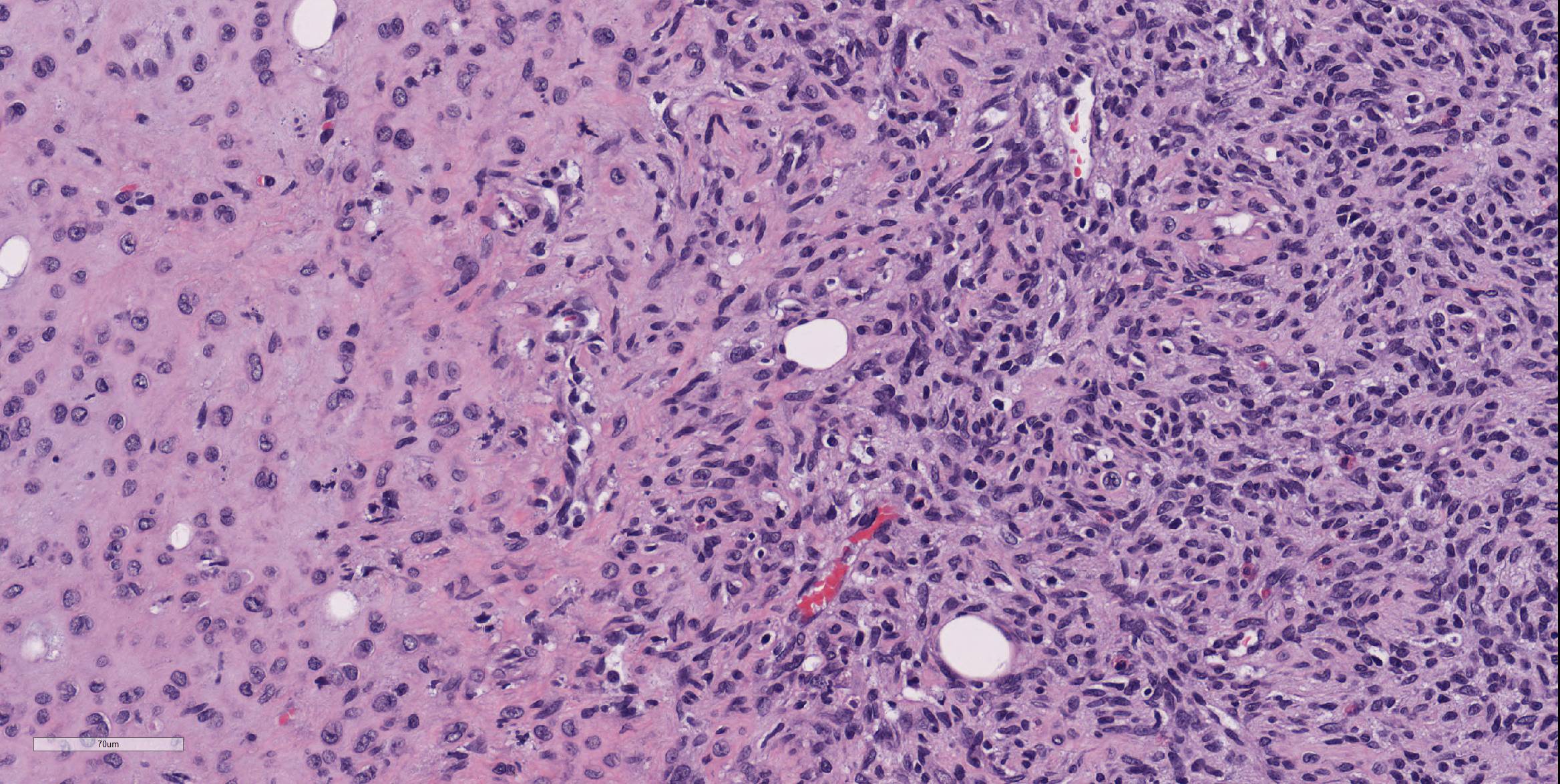

Microscopic description:

The submitted section consists of a large vaguely encapsulated, highly cellular and pleomorphic infiltrative neoplastic mesenteric mass that arises from the lamina propria of the squamous stomach with effacement of the submucosa and muscularis proper. The neoplasm has a pleomorphic appearance ranging from bland solid nodular more fibrous appearance to regions of high cellularity comprising of whorls or short intersecting fascicles of spindle to epithelioid cells in abundant hyalinized to vacuolated stroma. In general, the neoplastic cells don't have clearly discernible cell borders and contain variable amounts of eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm and or fibrous stroma. The nuclei were small to moderately sized, oval or indented with a finely granular to vesiculated chromatin infrequently with a prominent nucleolus. In large sections of the mass, there are numerous variably sized pseudocystic or variably sized spaces with degenerate cells or basophilic material admixed with distended vascular channels filled with blood. Mitotic figures are 3-4 per 10 40X objective field.

Immunohistochemistry:

The neoplasm was strongly positive for both c-KIT and Vimentin with sparse for S100 and was negative for pancytokeratin.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Stomach/Mesenteric masses: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

Contributor's comment:

The most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract in humans is gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), however, spontaneous GISTs are rare in rats and primates.2,3,9,11 In canines, these have been well characterized for their comparative morphology and biological behavior similar to humans.4 Historically, they were classified as smooth muscle tumors such as leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, but it is now thought that these tumors arise from the cells of Cajal.3,9 GISTs can occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract but are commonly found in the stomach. The appearance of these types of tumors can vary from soft, tan nodules to complex cystic masses depending on size and malignancy.3,4 GISTs can be divided into 4 types including smooth muscle, neural, combined smooth muscle-neural and uncommitted.3 For this case, due to the solid and cystic appearance and variable morphological pattern ranging from spindle to epithelioid, the differentials considered were GIST, adenocarcinoma, fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, mesothelioma, nerves sheath tumors and vascular origin tumors (lymphangiosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma). On the basis of its location (gastric location), histomorphologic features, and immunohistochemical expression pattern (diffuse strong c-KIT (CD117) and vimentin positivity, sparse S100 reactivity and lack of pancytokeratin expression), the abdominal masses were diagnosed as gastric origin- GIST. Smooth Muscle Actin (SMA), a marker of leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma and cluster of differentiation (CD) 34 which can label both GISTs and smooth muscle origin tumors were not performed in this case. A strong c-KIT positivity is usually considered as the gold standard in the diagnosis of which is the gold standard marker for GISTs.2,4,9 In this case, there was no distant metastasis other than mesenteric and splenic capsular involvement.

GISTs are positive for KIT tyrosine kinase receptor, which is also seen in the cells of Cajal, neural cells in the gastrointestinal tract that modulate gut motility. Around 70-80% of human GISTs are also positive for CD34, 30-40% of them are positive for ?-smooth muscle actin, <5% are positive for desmin and S100-protein.3,9 These tumors develop a gain of function mutation of the KIT gene commonly in exons 9, 11, 13, and 17. In humans, there are reports of familial GISTs due to mutations in the KIT and PDGFRA gene.9 GISTs have been experimentally induced in rats using a duodenal reflux model but spontaneous findings in chronic studies using rats are usually under reported.7,9 The prognosis of GISTs is based primarily upon the size and location of the tumor as well as its mitotic rate, distant metastasis and degree of necrosis.4,9

Contributing Institution:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Cambridge, MA 02139

JPC diagnosis:

Stomach, mesentery: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, malignant, Long Evans rat, rodent.

JPC comment:

While this case was in a rat, there are documented cases of GIST in many species, including dogs, cats10, horses, mice, and many others. Recent reports in horses have documented GISTs arising from the colon6, as well as a discrete intra-abdominal mass with vascular connections to the transverse colon, mesocolon, jejunal mesentery, and the omentum, but still arising from the colon. That particular neoplasm was unusual in that it was characterized by immunoreactivity for desmin, as well as having multinucleated cells, and a predominately neuroid morphology of neoplastic cells.8

Because the majority of spindle cell neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract in rats and mice used in research settings are diagnosed as smooth muscle tumors, and they cannot definitively be distinguished on H&E slides, immunohistochemistry is critical to determine the cell of origin. An examination of mouse and rat gastrointestinal spindle neoplasms in the National Toxicology Program found that there were few GISTs in rats, but that up to 60% of the previously classified smooth muscle tumors of mice demonstrated CKIT immunopositivity, and likely GISTs.5

While CD117 has been the gold standard to identify canine GIST, up to 5-10% of human GIST cases are negative for CD117. The immunohistochemical stain DOG1 (discovered on GIST protein 1) was shown to have a high sensitivity and specificity for human GISTs and was subsequently tested for canine GIST. Most canine GISTs had a similar IHC morphology for CD117 and DOG1, but some neoplasms were identified as GIST after negative CD117 and positive DOG1 results. Ultimately, DOG1 may have a higher sensitivity and specificity for canine GIST than CD117 but running both may provide the most information to the pathologist.1

References:

1. Dailey DD, Ehrhart EJ, Duval DL, Bass T, Powers BE. DOG1 is a sensitive and specific immunohistochemical marker for diagnosis of canine gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2015. 27(3):268-277.

2. Fujimoto H, Shibutani M, Kuroiwa K, Inoue K, Woo GH, Hirose M. A case report of a spontaneous gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) occurring in a F344 Rat. Toxicol. Pathol. 34, 164?167 (2006).

3. Hamilton, S. R. & Aaltonen, L. A. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. IARC Press (200AD). doi:10.1183/09031936.01.00275301.

4. Hayes S, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V, Gregory-Bryson E, Kiupel M. Classification of canine nonangiogenic, nonlymphogenic, gastrointestinal sarcomas based on microscopic, immunohistochemical, and molecular characteristics. Vet Pathol. 2013 Sep; 50(5):779-88.

5. Janardhan KS, Venkannagari P, Jensen H, et al. Do GISTs occur in rats and mice? Immunohistochemical characterization of gastrointestinal tumors diagnosed as smooth muscle tumors in the National Toxicology Program. Toxicologic Pathology. 2019. 47(5):577-584.

6. Malberg JA, Webb BT, Hackett ES. Colonic gastrointestinal stromal tumor resulting in recurrent colic and hematochezia in a warmblood gelding. Can Vet J. 2014. 55:471-474.

7. Mukaisho, K. I. et al. Induction of gastric GIST in rat and establishment of GIST cell line. Cancer Lett. 231, 295?303 (2006).

8. Muravnick KB, Parente EJ, Del Piero F. An atypical equine gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2009. 21:387-390.

9. Shinomura, Y, Kinoshita, K, Tsutsui, S, Hirota, S. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Gastroenterol. 40, 775?780 (2005).

10. Suwa A, Shimoda T. Intestinal gastrointestinal stromal tumor in a cat. J Vet Med Sci. 2017. 79(3):562-566.

11. Yugendar R. Bommineni, Edward J. Dick, Jr., Gene B. Hubbard. Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors in a Baboon, a Spider Monkey and a Chimpanzee and a Review of the Literature. J Med Primatol. 2009 Jun; 38(3): 199?203.