CASE 2: S19-3401-3 (4153161-00)

Signalment:

6-year-old, mare, Hackney, Equus ferus caballus

History:

The provided sample was from a subcutaneous mass on the neck. The horse has no

travel history outside the state of Florida, USA.

Gross Pathology:

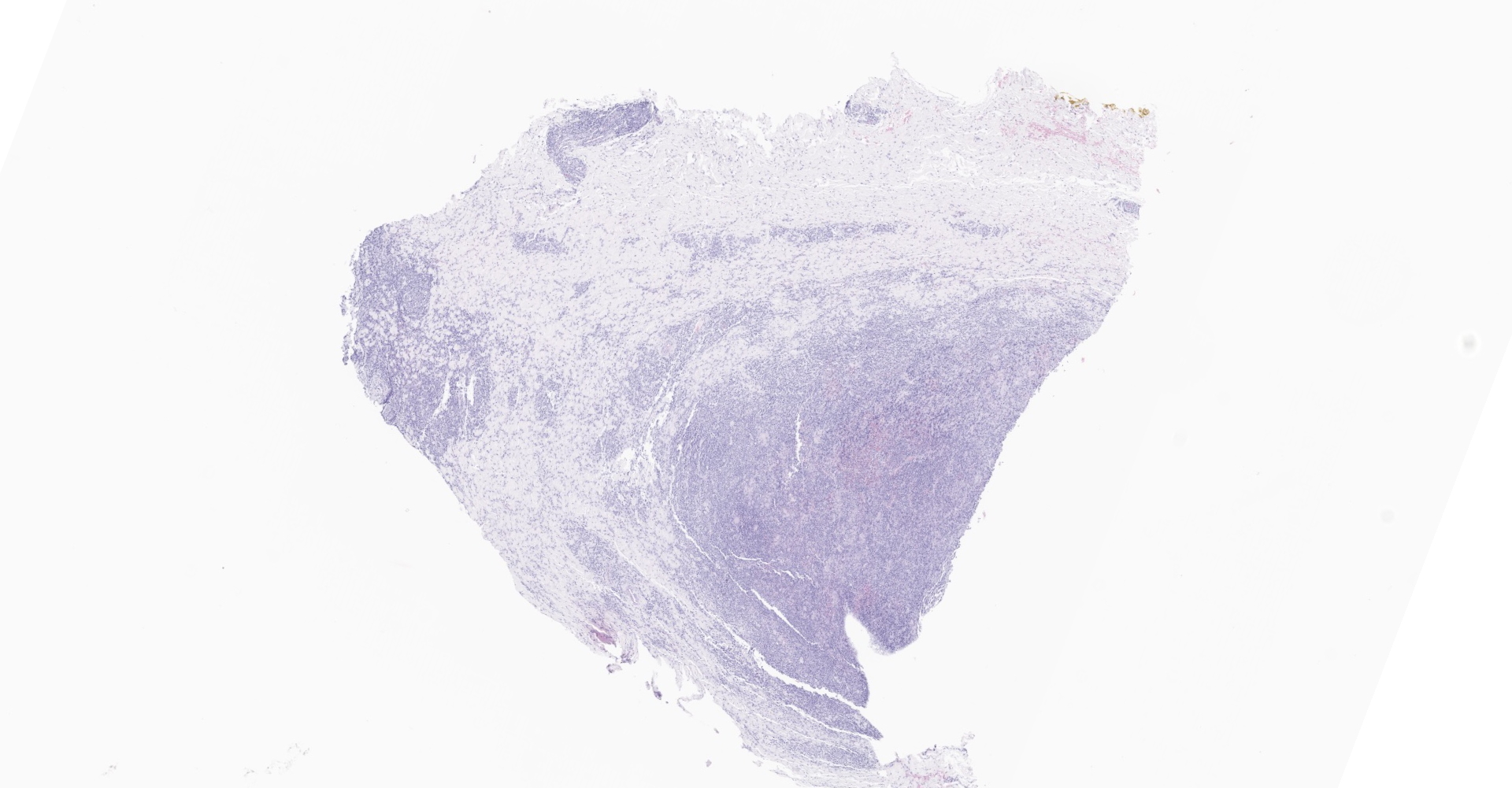

Received is a roughly elliptical 1.7 x 1.2 x 0.6 cm, light tan to brown firm tissue.

Laboratory results:

Immunohistochemistry for Leishmania spp. is immunoreactive. PCR is negative.

Microscopic description:

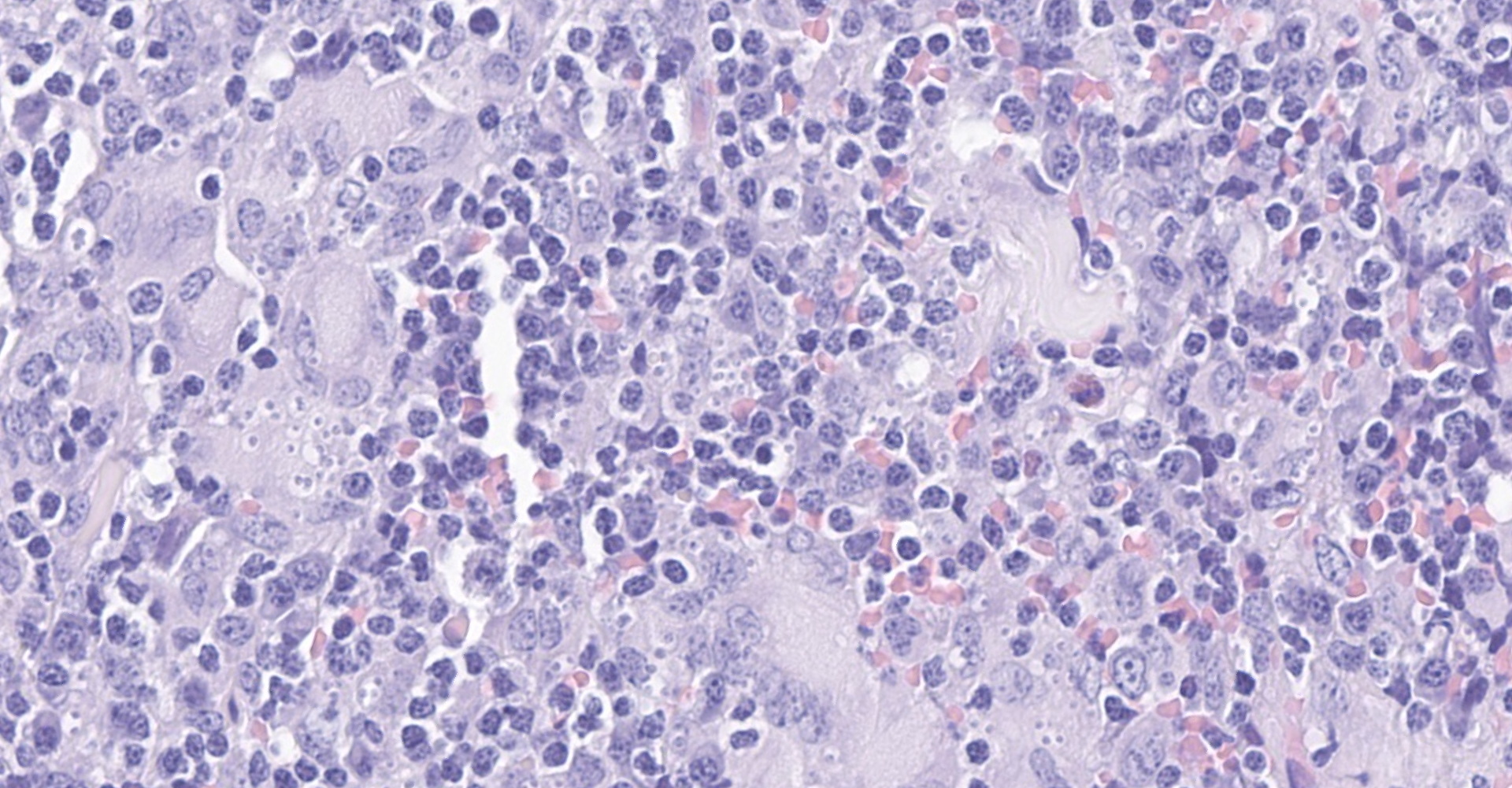

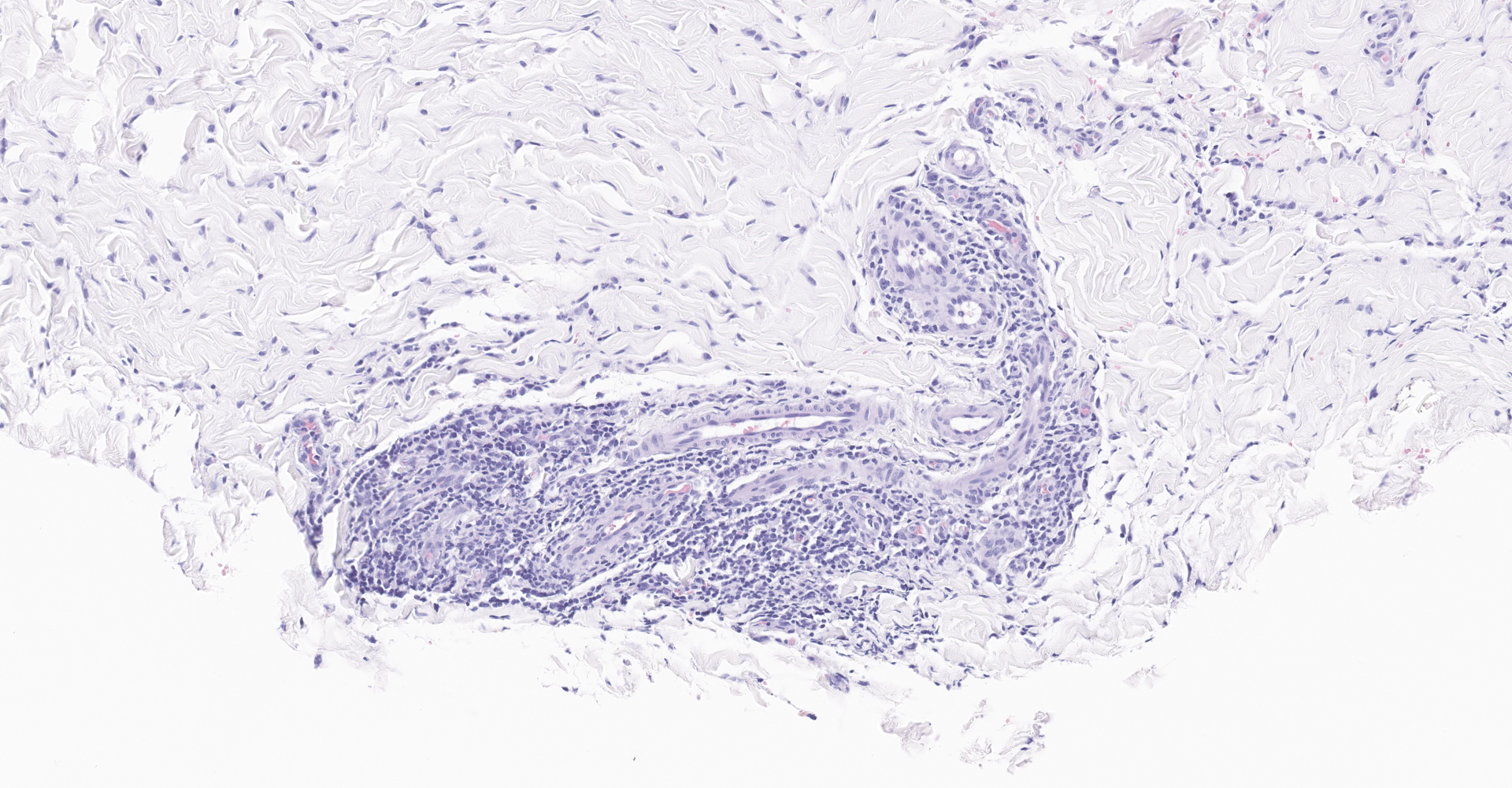

The fibrous connective tissue is moderately expanded by large numbers of macrophages and epithelioid macrophages admixed with moderate number of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and low to moderate numbers of multinucleated giant cells. Numerous macrophages contain one to eight pale eosinophilic, round, protozoal organisms (amastigotes) that are 2-3 ?m in diameter, stain with a Giemsa histochemical stain, have an oval nucleus and a kinetoplast that is orientated perpendicular to the nucleus. Intrahistiocytic amastigotes are frequently surrounded by a thin optically clear halo (parasitophorous vacuole).

There are multifocal areas within the larger nodule of inflammation of hypereosinophilic and degenerate collagen.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Dermatitis and panniculitis, granulomatous, lymphoplasmacytic, chronic, multifocal to coalescing, marked, with myriads of intrahistiocytic amastigotes and fewer extracellular amastigotes, subcutaneous mass from neck.

Contributor's comment:

Leishmaniasis is a zoonotic disease caused by Leishmania spp., an obligate intracellular

protozoa. Leishmania spp. are found on every continent except Australia and Antarctica. Leishmaniasis has three types of disease presentations: cutaneous, visceral, and mucocutaneous. The disease presentation depends on the species of Leishmania and the host immune responses.10 Most of the Leishmania species (>85%) only cause cutaneous lesions. Therefore, cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common presentation in humans. However, the prevalence of cutaneous leishmaniasis in domestic animals is largely unknown9 and likely underdiagnosed as it is suspected the majority of infections have mild clinical disease and undergo spontaneous regression.7 To date, only two Leishmania species, L. donovani and L. infantum (also known as L. chagasi), are known to cause visceral leishmaniasis in mammals. In cases of visceral leishmaniasis, there is often concurrent cutaneous involvement. The spectrum of the severity of the cutaneous lesions in leishmaniasis reflects the dynamics of host immune responses. In general, a balanced Th1 response with proper IFN-? dominant delayed type hypersensitivity promotes parasite killing and resolution of disease. However, an overly strong Th1 response could cause tissue damage and leads to severe, immune-mediated mucocutaneous manifestation. On the other end of the spectrum, an antibody dominant, or a Th2-skewed response that lacks IFN-?, is associated with a high parasite load and diffuse, severe cutaneous disease.14

The sandfly is the known vector for Leishmania spp. The sandflies acquire cell-associated amastigotes from the blood meal of an infected host. The amastigotes transform to the promastigote stage in the gut and migrate to the proboscis. The promastigotes are then regurgitated into the skin when the sandfly bites a new host. Once in the skin, the promastigotes are quickly phagocytosed by macrophages. Within the phagolysosome the promastigotes are protected from degradation from the macrophages, mature into amastigotes, and start to multiply inside the macrophages. Eventually the macrophages burst from the amastigote burden releasing amastigotes into the surrounding tissue to then be phagocytosed by other macrophages. Different species of sandflies are responsible for different species of Leishmania parasite. There are at least 40 species of Leishmania parasites listed in the taxonomy database in NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) website and more than 30 species of sandflies serve as vectors for

Leishmania parasite. And different species of Leishmania parasite seem to rely on different species of mammals as primary reservoirs to maintain its transmission cycle. For example, dogs serve as a natural reservoir for L. infantum. Sloths, hyraxes, opossums and rodents are other documented reservoirs for various species of Leishmania.3 In dogs, in addition to horizontal transmission by sandflies12, vertical transmission of L. infantum from naturally infected, pregnant bitch to puppies has been proven15 and is believed to contribute to the maintenance of the pathogen in endemic areas.

The histiocytic and lymphocytic dermatitis is a consistent feature for cutaneous leishmaniasis. However, the burden of the protozoa could be variable which reflects the dynamics of the interplay between the host and the pathogen. Furthermore, the incubation time of cutaneous leishmaniasis is highly variable from several month to seven years. Spontaneous regression and recurrence of cutaneous leishmaniasis have been reported in cats15 and horses.8

In the United States, while most cases reflect travel patterns, cutaneous leishmaniasis is considered endemic in Texas and Oklahoma and North Dakota, with identification of autochthonous cutaneous leishmaniasis human cases and detection of female Lutzomyia anthophora sand flies at the residences of the case-patients.5 In the similar geographical regions in Texas where human autochthonous cutaneous leishmaniasis were reported, feline autochthonous cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by the same Leishmania species (L. Mexicana) have also been reported sporadically.16 Despite Florida not currently considered endemic for leishmaniasis in people, there has be a reported case of equine autochthonous cutaneous leishmaniasis case in Florida caused by L. siamensis in 2011.11 L. siamensis is an emergent leishmania species that is not genetically close to the leishmania species in the New World and in the Old world. It was first reported in a visceral leishmaniasis patient with AIDS in Thailand and subsequently in at least four horses with cutaneous leishmaniasis in central Europe.8 In addition, an autochthonous bovine cutaneous leishmaniasis case caused by L. siamensis was reported in Switzerland in 2010.6 The presented case is the second recognized horse native to central Florida with no travel history outside Florida, suggesting Florida is endemic for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Leishmaniasis should be considered as an endemic disease in Florida and be included as a differential diagnosis of nodular skin disease in horses with no travel history.

Contributing Institution:

University

of Florida

College of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Comparative, Diagnostic, and Population Medicine

P.O.

Box 100123

Gainesville, FL 32610-0123

https://www.vetmed.ufl.edu/

JPC diagnosis:

Dermis: Dermatitis, granulomatous, focally extensive, severe, with numerous intrahistiocytic amastigotes.

JPC comment:

The contributor provides an excellent review of Leishmania spp. One hallmark feature of this protozoan is the presence of a kinetoplast. This structure is a complex organization of circular DNA in a large mitochondrion. The circles of DNA contain many copies of mitochondrial DNA, composed of minicircles and maxicircles. Maxicircles are similar to those of mitochondrial DNA is other eukaryotes, but minicircles are involved in RNA editing of maxicircle encoded transcripts. Leishmania tarentolae has been used as a research model successfully, and sequencing of L. infantum and L. baziliensis has shown remarkable conservation of minicircle DNA sequences across species. However, there exists a high degree of heterogeneity and diversity of maxicircle DNA, providing another way to identify and classify individual species within the clade of kinetoplastids.4

The parasitophorous vacuole is an important structure in this disease, with contributions from the host cell as well as the parasite. The molecular composition of the host contributed components have partially been identified, while the contributions from the parasite are largely elusive. Leishmania spp parasitophorus vacuoles have many shared characteristics with phagolysosomes, including the lysosome-associated proteins 1 and 2 (LAMP1, LAMP2) and ATPase. Also expressed and present are MHC class II, the glycoprotein gp91phox portion of NADPH oxidase complex, macrosialin, and cathepsin proteases B, D, H, and L. Additional molecules have been identified, and research as to their function remains to be conducted.17

In the recent past, multi-locus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) was the reference technique for identifying Leishmania species, which often resulted in classification into species complexes. However, more recent molecular techniques based on either single gene sequences or multi-locus sequences, categorize in a definitive manner that does not support species complexes. Within major groups, markers such as MLSA, microsatellites or genome-wide SNPs are most appropriate. By leveraging molecular techniques, it allows for research on genetic drift and evolution of Leishmania, and has resulted in a clonal evolution hypothesis, with rare sexual recombination events.13

There is some variability in participant slides for this case, with some containing adnexal structures which were helpful for tissue identification. The moderator discussed the potential differential diagnosis of cutaneous histoplasmosis in this horse. However, there is a paucity of Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum reported in horses in the literature, with horses more often affected by Histoplasma capsulatum var. farciminosum (equine Histoplasmosis). The latter disease is of a more nodular nature, and frequently results in ulceration, exudation, scarring, and spreads via lymphatics.

The lesion of leishmaniasis typically contains a significant plasmacytic component. In this case, while a few plasma cells were observed, many felt inclusion in the morphologic diagnosis was not warranted. Definitions of 'granulomatous' inflammation may include plasma cells as a component of chronic inflammatory cells,2 or it may specifically refer to macrophages, epithelioid macrophages, and multinucleated giant cells.1 In this case, we choose to include the small numbers of plasma cells in the term 'granulomatous.'

References:

1. Ackerman MR. Inflammation and Healing. In: Zachary JF ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, 6th Ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2017;108.

2. Albert D, Block AM, Bruce BB, et al. Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, 32 Ed. Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier. 2012:803.

3. Ashford RW. Leishmaniasis reservoirs and their significance in control. Clin Dermatol. 1996;14: 523-532.

4. Camacho E, Rastrojo A, Sanchiz A, et al. Leishmania mitochondrial genomes: Maxicircle structure and heterogeneity of minicircles. Genes. 2019;10(10):758.

5. Clarke CF, Bradley KK, Wright JH, Glowicz J. Case report: Emergence of autochthonous cutaneous leishmaniasis in northeastern Texas and southeastern Oklahoma. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88: 157-161.

6. Lobsiger L, Mu?ller N, Schweizer T, et al. An autochthonous case of cutaneous bovine leishmaniasis in Switzerland. Vet Parasitol. 2010;169: 408-414.

7. Mhadhbi M, Sassi A. Infection of the equine population by Leishmania parasites. Equine Vet J. 2020;52: 28-33.

8. Mu?ller N, Welle M, Lobsiger L, et al. Occurrence of Leishmania sp. in cutaneous lesions of horses in Central Europe. Vet Parasitol. 2009;166: 346-351.

9. Petersen CA. Leishmaniasis, an emerging disease found in companion animals in the United States. Top Companion Anim Med. 2009;24: 182-188.

10. Reithinger R, Dujardin JC, Louzir H, Pirmez C, Alexander B, Brooker S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7: 581-596.

11. Reuss SM, Dunbar MD, Calderwood Mays MB, et al. Autochthonous Leishmania siamensis in horse, Florida, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18: 1545-1547.

12. Schaut RG, Robles-Murguia M, Juelsgaard R, et al. Vectorborne Transmission of Leishmania infantum from Hounds, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21: 2209-2212.

13. Schonian G. Genetics and Evolution of Leishmania parasites. Infection, Genetics, and Evolution. 2017;50:93-94.

14. Scott P, Novais FO. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: immune responses in protection and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16: 581-592.

15. Toepp AJ, Bennett C, Scott B, Senesac R, Oleson JJ, Petersen CA. Maternal Leishmania infantum infection status has significant impact on leishmaniasis in offspring. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13: e0007058.

16. Trainor KE, Porter BF, Logan KS, Hoffman RJ, Snowden KF. Eight cases of feline cutaneous leishmaniasis in Texas. Vet Pathol. 2010;47: 1076-1081.

17. Young J, Kima PE. The Leishmania parasitophorous vacuole membrane at the parasite-host interface. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 2019;92:511-521.