CASE 4: K18-1448 (4127786-00)

Signalment:

15.5 year old castrated domestic shorthair cat (Felis catus)

History:

An adult cat was treated medically after he was presented for loss of appetite and lethargy. Five days later the cat represented with no change in status. Following fluid therapy and another two days, the cat was examined by ultrasound. An intestinal foreign body was diagnosed and abdominal surgery performed. In addition to removing an unspecified foreign body from small intestine, the surgeon excised a discreet cystic mass on the liver. It was submitted for diagnosis. The cat made an uneventful recovery.

Gross Pathology:

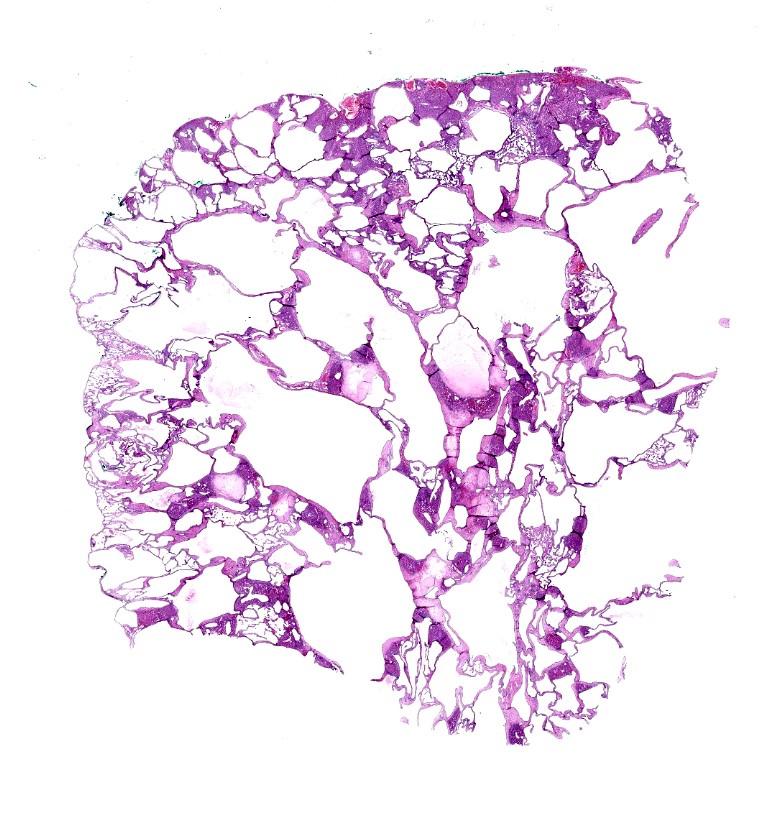

The submitted 54 x 40 x 25 mm multilocular cystic mass released clear water-like fluid when incised.

Laboratory results:

None.

Microscopic description:

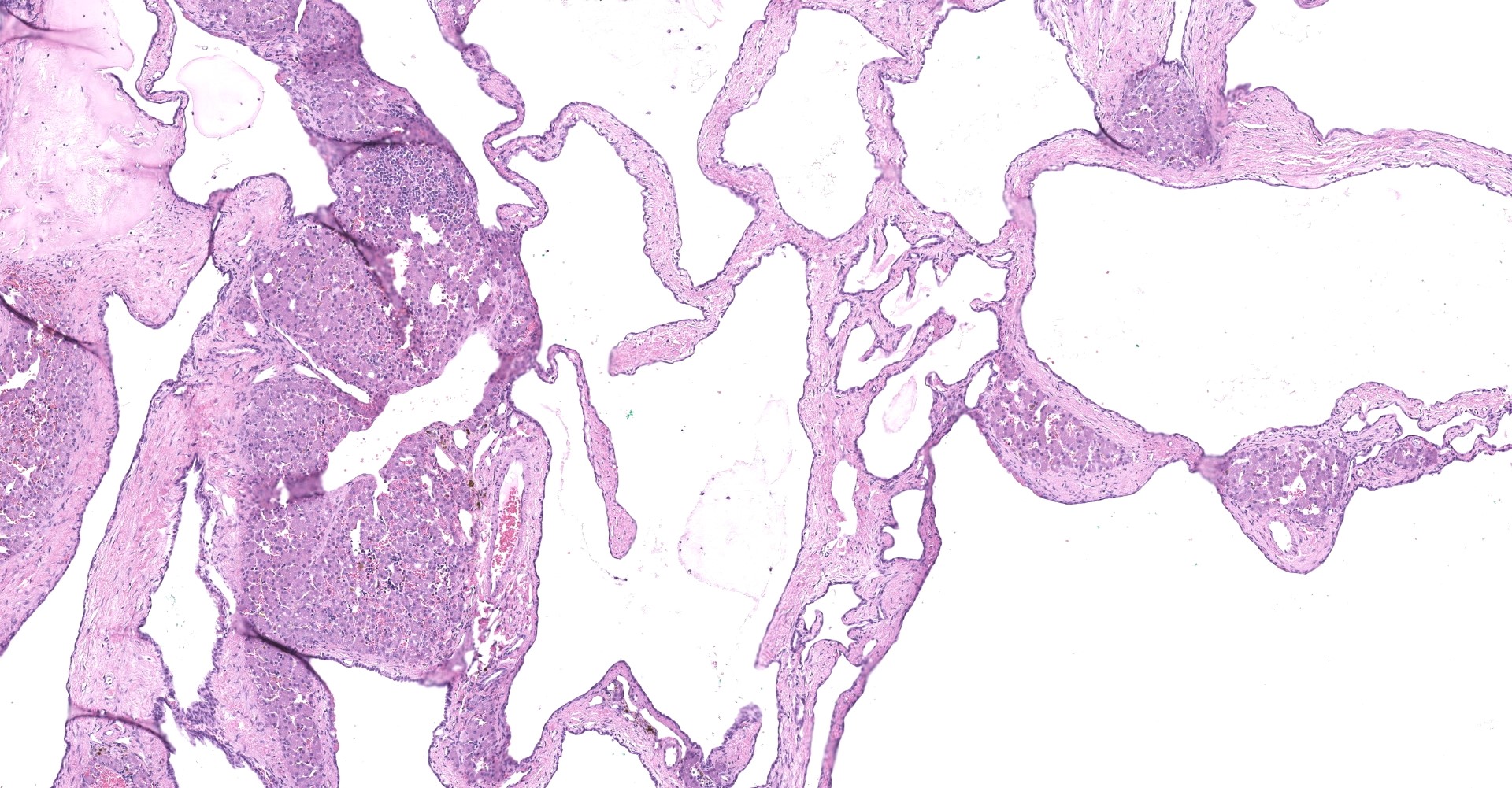

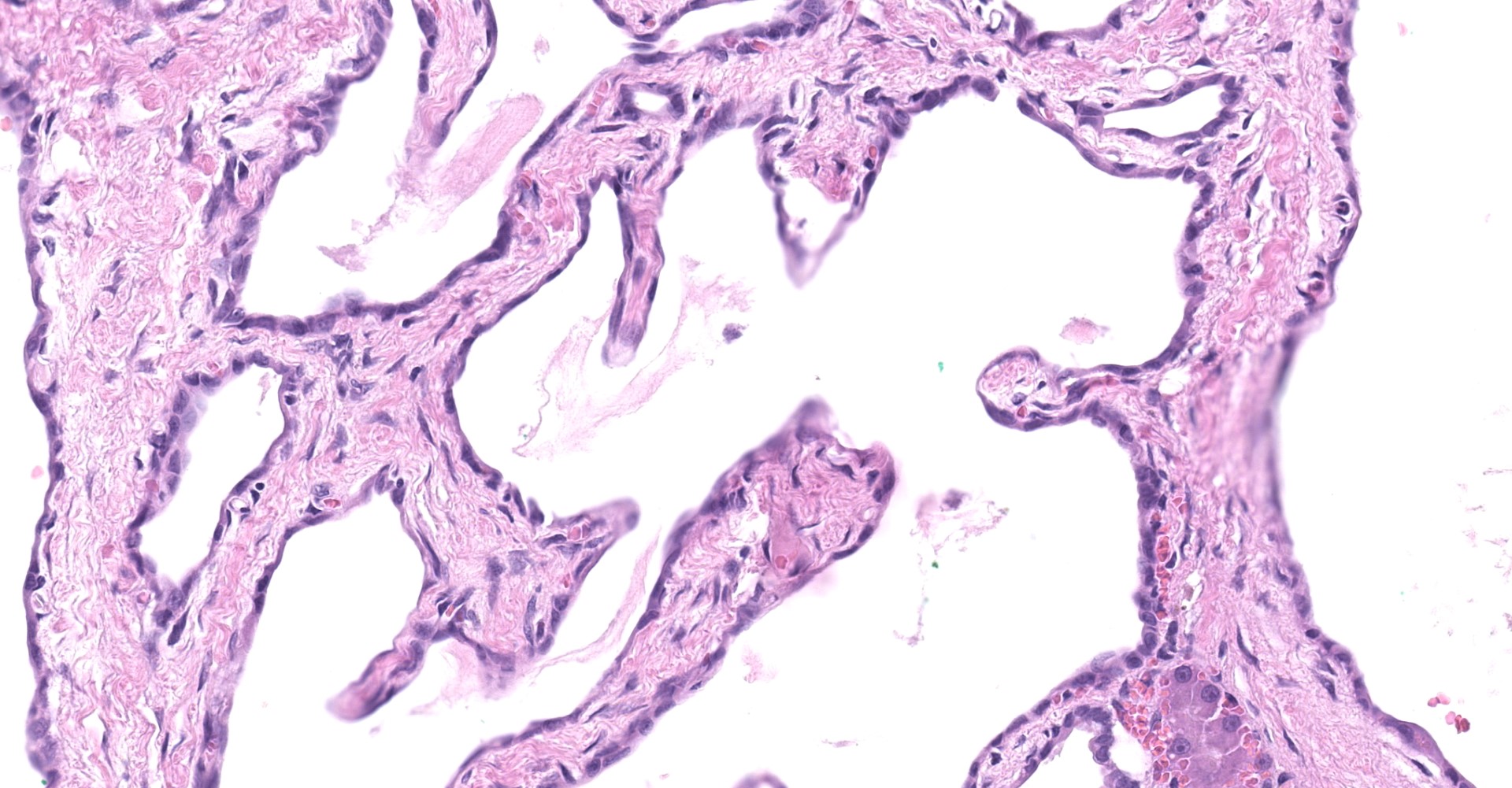

Liver: The submitted mass consists of cystic spaces separating small islands of hepatic parenchyma. Cystic spaces vary from 300 ? 3,500 µm. Short trabeculae projecting into some lumina. Cysts are lined by low simple cuboidal epithelium encompassed by a variable amount of fibrovascular tissue. Cysts contain amorphous lightly eosinophilic material and scant histiocytes-macrophages. Bile-like pigment is not identified. Epithelium that is indistinguishable from cyst lining interdigitates with islands of hepatic parenchyma, some in branching configurations. Persisting hepatic plates are orderly. Portal triads are present but sparse and mildly disordered. Hepatocytes contain a small amount of brown-yellow granular pigment. Small islands of hematopoietic cells are throughout. There is expansion of some fibrous septa by edema, fibrin effusion, and hemorrhage.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Liver: Bile duct hamartoma (ductal plate malformation; von Meyenburg complex).

Contributor's comment:

Biliary duct hamartomas (BDH) are well recognized in human medicine. They must be distinguished from neoplastic or parasitic masses and from granulomas when detected by noninvasive imaging or exploratory surgery. Most, in the form of von Meyenburg complexes, are biologically innocent. In one survey of liver lesions in 2,843 autopsies, von Meyenburg complexes were found in 5.6% of adults and in 0.9% of children.8 They occur as solitary or, more commonly, multiple masses. These malformations arise from the ductal plate which in normal development forms intrahepatic bile ducts.3 BDH are considered hamartomatous (from Greek: to err). In normal fetal ontogeny there is substantial pruning of the biliary tree as ducts and ductules develop. Typically what persist are redundant portions of the biliary tree.4 With the advent of noninvasive imaging such as ultrasound, CT and MRI they can be recognized throughout the liver.6 Failure to involute results in intrahepatic embryological remnants that persist into postnatal life. Some undergo cystic enlargement. A small proportion cause abdominal discomfort and may be mistaken for cholangitis.6 As with other developmental disorders of the biliary tree, a small fraction of BDH may be precancerous.8

Congenital cystic disorders of the liver remain a complex and difficult entity in veterinary pathology. A current classification for congenital cystic disease of the liver in animals proposes three entities: congenital dilation of large and segmental bile ducts (morphologically similar to Caroli's disease); juvenile polycystic disease/congenital hepatic fibrosis; and adult polycystic disease, including Von Meyenburg complexes.2

To this submitter's eye, the mass from this cat's liver most closely approximates a von Meyenburg complex as defined in human pathology.3,7,8 In people these complexes are generally clinically silent, as appeared to be the case here. Histological features are the presence of a variable number of dilated bile ducts embedded in fibrous stroma, which may be hyalinized.3 These are lined by simple cuboidal to low columnar epithelium encompassing ectactic ramifying lumina.7 They contain either eosinophilic proteinaceous material, as here, or bile-like pigment. This mass was >5 cm, which is large relative to most Meyenburg complexes found in human patients (1 ? 15 mm).4 Differential possibilities include biliary adenoma and a Caroli-like disease. Biliary adenoma is unlikely as these lack islands of hepatocytes interspersed between tubules.2 Caroli-like disease is associated with extensive liver involvement (typically the whole organ, resulting in hepatomegaly), large duct formation, and clinical signs due to secondary bacterial cholangitis. Such features were absent here.

There are few reports of ductal plate malformations in feline species. A Caroli-type ductal plate malformation was reported in a kitten that also had a portosystemic shunt.5 Biliary cysts tentatively diagnosed as Von Meyenburg complexes are reported in lions.1

Contributing Institution:

http://www.uwyo.edu/wyovet/

JPC diagnosis:

Liver: Ductal plate malformation, fibrocystic (von Meyenburg's complex / biliary hamartoma).

JPC comment: There was energetic debate amongst participants in regard to the nomenclature of the morphologic diagnosis due to overlapping features of congential hepatic fibrocystic diseases, which in veterinary medicine have been proposed to be classified as adult polycystic disease (including von Meyenburg complexes), juvenile polycystic disease/congenital hepatic fibrosis, and congenital dilation of the large and segmental bile ducts (resembling Caroli disease in humans).2

Prior knowledge of the embryologic steps involved in the development of the biliary tree is beneficial in regard to understanding the pathogenesis von Meyenburg's complex and other ductal plate malformations. The liver's characteristic hepatic cords arise as a result of the early precursor cells of the liver (hepatoblasts) interacting with the capillary plexus of the vitelline veins.3 Hepatoblasts in contact with mesenchyme surrounding large future portal vein branches become smaller, forming the primitive ductal plate.3 These cells duplicate, forming a second layer, resulting in one layer in contact with the peripheral hepatoblasts and the second in contact with the mesenchyme surrounding the portal vein.3 These epithelial cells become the lobular and portal layers of the ductal plate, respectively, and are separated by a slitlike lumen.2 Smaller branches of the portal vein are subsequently surrounded as the process repeats over the following weeks.3

The hepatic plate then undergoes remodeling, beginning with a dilation of short segments of the double-layered ductal plates, forming tubular dilations that later detach from the lobular layer of the ductal plate due to infiltrating mesenchyme, forming primitive bile ducts.3 Not all tubular dilations result in the formation of bile ducts, as excessive components gradually disappear, presumably by apoptosis, suggesting remodeling is a selective process.3

Ductal plate malformations arise due to disruption of the highly complex and epithelial-mesenchymal interactions involved in their development and subsequent remodeling.3 Hepatic fibrosis and cysts have been identified in a significant proportion of domestic felines with concurrent polycystic kidney disease, suggesting a similar pathogenesis of each lesion's development due to an inherited autosomal dominant mutation of the gene responsible for encoding polycystin 1 (PKD1) that closely resembles the adult form of polycystic kidney disease in humans.2 However, the association of these two lesions was not commonly observed in a study of 90 necropsied non-domestic felids.1 Lions were found to be six times more likely to have cystic biliary lesions than other nondomestic felids; however, none of the seven affected lions were found to have concurrent renal cysts.1 Of the 14 non-domestic felines necropsied, only one of had a concurrent renal cyst (a cougar).1

References:

1. Bernard JM, Newkirk KM, McRee AE, Whittemore JC, Ramsay EC. Hepatic lesions in 90 captive nondomestic felids presented for autopsy. Vet Pathol. 2015;52:369-376.

2. Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals, vol. 2, 6th ed. St. Louis, MO; Elsevier; 2016, p. 264-265, 348.

3. Desmet VJ. Ludwig symposium on biliary disorders--part I. Pathogenesis of ductal plate abnormalities. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:80-89.

4. Lev-Toaff AS, Bach AM, Wechsler RJ, et al. The radiologic and pathologic spectrum of biliary hamartomas. Am J Roentgenol 1995;165:309?313.

5. Roberts ML, Rine S, Lam A. Caroli's-type ductal plate malformation and a portosystemic shunt in a 4-month-old kitten. J Feline Med Surg. 2018;4(2):2055116918812329. Published 2018 Nov 20. doi:10.1177/2055116918812329

6. Sinakos E, Papalavrentios L, Chourmouzi,D et al. The clinical presentation of Von Meyenburg complexes. Hippokratia. 2011;15:170?173.

7. Thommesen N. Biliary hamartomas (von Meyenburg complexes) in liver needle biopsies. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1978;86:93-99..

8. Zimmermann A, Benign epithelial tumors and hamartomas of the biliary tract. Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions of the Hepatobiliary Tract. Springer International Publishing Switzerland. 259-266. 2017