Signalment:

Gross Description:

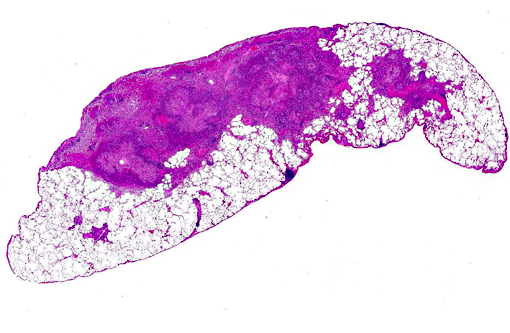

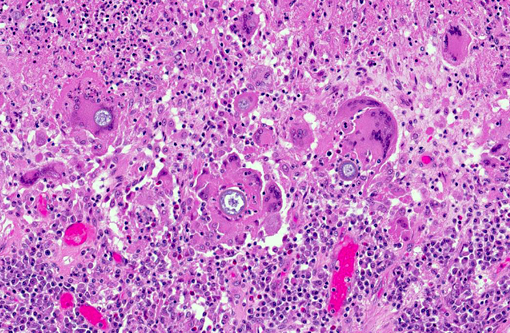

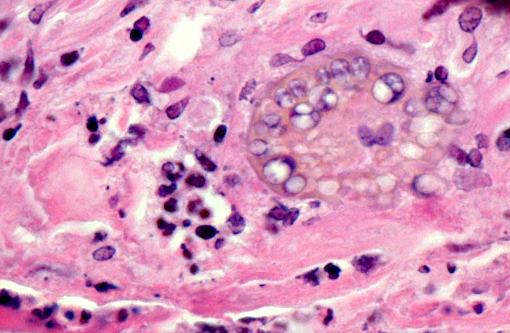

Histopathologic Description:

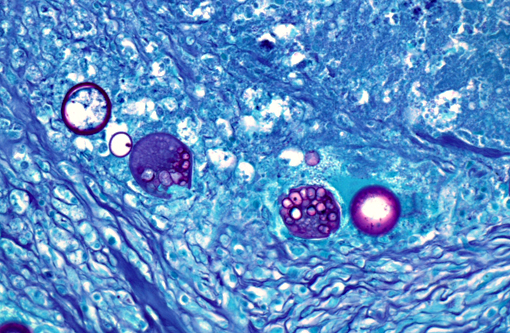

The periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reaction revealed that each of the spherules had a PAS positive wall.

Similar granulomatous inflammation and fungal spherules are present within the tracheobronchial and mediastinal lymph nodes (not submitted).Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

All tissues were evaluated with immunohistochemistry for orthropoxvirus antigen and all tissues were immunonegative suggesting either viral clearance (consistent with this animals survival) or that the amount of antigen is too low for detection by immunohistochemistry.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Coccidioidomycosis is a fungal disease found only in the Western Hemisphere in semi-arid regions known as the Lower Sonoran Life Zone. This zone within the United States encompasses the southern parts of Texas, Arizona, New Mexico and much of central and southern California.(12,15) Endemic regions outside of the United States include semiarid regions of Mexico, especially northern Mexico, as well as smaller endemic foci within Central and South America.(15) It is caused by a geophilic dimorphic fungus of which two nearly identical species are recognized, Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. C. posadasii was recently proposed as a new species based on genetic and phenotypic analysis,(12) and is generically known as the non-California species with a geographically unique distribution. C. immitis is restricted to the endemic areas of California while C. posadasii is found outside of California.(15) In this case, Coccidioides posadasii is the most likely etiologic agent based on the travel history of this primate.Â

Infection with Coccidioides sp. occurs primarily via inhalation of arthroconidia (also called arthrospores) that are aerosolized when the soil is disturbed by wind or human activities. After inhalation, the arthroconidia enlarge and become spherules that eventually undergo endosporulation. After endosporulation, the spherules rupture releasing hundreds of endospores into the surrounding tissue. These released endospores also mature into new spherules, and the cycle continues until host control is achieved.(14)

Coccidioides spp. appear capable of infecting all mammals and at least some reptiles, but it has not been reported in avian species. The disease has been reported in several species of primates including lemurs, chimpanzees, gorillas, macaques, and baboons,(1-4,16,19,21) and many of these reports describe disseminated disease. As a group, primates appear particularly susceptible.(21)

In dogs, the majority of infections are limited to the lungs and associated hilar lymph nodes. In 20% of recognized infections in dogs and 50% of infections in cats there is dissemination to other sites. In dogs, the most common sites of dissemination are the bones, joints, and lymph nodes, while in cats, the skin is the most common site of dissemination.(14) The sites of dissemination in non-human primates seems to follow a similar pattern as dogs and sites reported in the literature include the eye, bone, and esophagus.(2,4,5,16,18)

Pulmonary and disseminated histopathologic lesions consist of pyogranulomas or granulomas. There are frequently aggregates of intermixed neutrophils resulting from the initial reaction to the endospores released from matures spherules. The lesion forms a granuloma or pyogranuloma as it matures, and is composed of the common components of a granulomatous reaction including giant cells.(6)

In this case, there were no clinical signs that were attributed to coccidioidomycosis despite the extensive granulomatous inflammation in the examined sections. This finding of a subclinical infection is not surprising provided that serologic surveillance studies have shown that asymptomatic infections represent a high percentage of infections in humans and other animals. In a survey of dogs in Arizona, 70% of dogs with seropositivity were subclinically infected and exhibited no sign of disease.(20) Converse and Reed showed that 100% of naturally exposed monkeys developed subclinical infections after being contained in outdoor housing in a river basin for a year in an endemic region (Tucson, Arizona). None of these monkeys exhibited clinical signs of disease, but all were positive by a coccidiodin skin test and complement fixation test; while 40% of the exposed monkeys had histological lesions.(10) A survey of nonhuman primates housed outdoors at the California Primate Research Center in 1977-78 showed that four out of 119 (3%) primates were seropositive; the seropositive cases were attributed to a dust storm that affected the area because there were no positive cases when they were surveyed before the dust storm.(1) In humans, approximately 60 percent of infected persons are asymptomatic; the remainder can develop manifestations that range from mild to moderate influenza-like illness to pneumonia. Overall, less than 5 percent of infected persons have progressive pulmonary infection or extrapulmonary dissemination of the disease.(17)

Additionally in humans, coccidioidal pneumonia may be associated with erythema nodosum, especially in females.(17) Erythema nodosum is characterized by panniculitis of the lower extremities, especially over the shins, and is due to an immunologic response to a variety of causes. A similar condition has not been described in the reports of coccidioidomycosis in animals.Â

We can only speculate on the source of infection in this case, but this monkey most likely inhaled dust-borne arthrospores when it was in Texas; this would mean that the fungus is C. posadasii. Research by Converse and Reed showed that infection can be established after aerosol exposure of rhesus macaques to as few as 10 arthrospores.(10)

In the last decade, the number of reported cases in humans has increased, but the reason for this increase is uncertain. A multitude of contributing factors have been identified and include increased population in the endemic area, climactic change (drought and increasing temperatures in southwestern United States), dust storms, soil disturbance caused by increased construction activity, growing numbers of persons who are immunocompromised or have other risk factors for severe disease, and immigration of previously unexposed persons from areas where coccidioidomycosis is not endemic.(7,8)

Antemortem diagnosis of coccidiomycosis in animals is primarily done with serology and uses the same reagents and controls as for serodiagnosis of humans. There is overlap of seropositivity with clinical disease and subclinical disease in dogs, but seropositivity appears to correlate well with clinically important disease in cats.(14)

Morphology of the Coccidioides spherules in histological sections is fairly unique. Other fungal organisms with similar but distinguishable morphology include Emmonsia spp., Blastomyces dermatitidis, and Rhinosporidium seeberi. The major distinguishing factor of coccidial spherules is the formation of thick walled endospores within the coccidioidal spherule as it matures. Blastomyces dermatitidis does not form endospores but forms broad-based buds and is smaller than mature coccidial spherules. Rhinosporidium seeberi forms endospores that have thin walls. In addition, rhinosporidial sporangia are much larger than coccidioidal spherules. Emmonsia spp. have the closest morphology but do not form thick-walled endospores, but rather form fruiting bodies that line the interior of the wall and form a honeycomb pattern which are much less distinct than those of Coccidioides spp. Additionally, Emmonsia spp. adiaspore walls are thicker than Coccidioides sp.(6) Fungal culture, immunohistochemistry (IHC), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and in situ hybridization (ISH) are other methods to provide an unequivocal diagnosis. Fungal cultures must be treated with precaution because the infectious arthroconidia may develop after incubation at room temperature.(14) Research was conducted under an IACUC approved protocol in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act, PHS Policy, and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals. The facility where this research was conducted is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, International and adheres to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 2011.

The research described herein was sponsored by the Office of Biodefense Research Affairs (OBRA)/ National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) with interagency agreement (A120-B.11) between USAMRIID and NIAID.

Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

References:

2. Bellini S, Hubbard GB, Kaufman L. Spontaneous fatal coccidioidomycosis in a native-born hybrid baboon (Papio cynocephalus anubis/Papio cynocephalus cynocephalus). Lab Anim Sci. Oct 1991;41(5):509-511.

3. Breznock AW, Henrickson RV, Silverman S, Schwartz LW. Coccidioidomycosis in a rhesus monkey. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1975;167(7):657-661.

4. Burton M, Morton RJ, Ramsay E, Stair EL. Coccidioidomycosis in a ring-tailed lemur. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986;189(9):1209-1211.

5. Castleman WL, Anderson J, Holmberg CA. Posterior paralysis and spinal osteomyelitis in a rhesus monkey with coccidioidomycosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc.1980;177(9):933-934.

6. Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsievier; 2007:644-645.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increase in Coccidioidomycosis - California, 2000-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(5):105-109.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increase in reported coccidioidomycosis - United States, 1998-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:217-221.

9. Cheville NF. Ultrastructural Pathology: The Comparative Cellular Basis of Disease. 2nd ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009:720-722.

10. Converse JL, Reed RE. Experimental epidemiology of coccidioidomycosis. Bacteriol Rev.1966;30(3):678-695.

11. Dabbs DJ. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:227.

12. Fisher MC, Koenig GL, White TJ, Taylor JW. Molecular and phenotypic description of Coccidioides posadasii sp. nov., previously recognized as the non-California population of Coccidioides immitis. Mycologia. 2002;94(1):73-84.

13. Goff AJ, Chapman J, Foster C, et al. A novel respiratory model of infection with monkeypox virus in cynomolgus macaques. J Virol. 2011;85(10):4898-4909.

14. Graupmann-Kuzma A, Valentine BA, Shubitz LF, Dial SM, Watrous B, Tornquist SJ. Coccidioidomycosis in dogs and cats: a review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2008;44(5):226-235.

15. Hector RF, Laniado-Laborin R. Coccidioidomycosis--a fungal disease of the Americas. PLoS Med. 2005;2(1):e2.

16. Johnson JH, Wolf AM, Edwards JF, et al. Disseminated coccidioidomycosis in a mandrill baboon (Mandrillus sphinx): a case report. J Zoo Wildl Med.1998;29(2):208-213.

17. Kirkland TN, Fierer J. Coccidioidomycosis: a reemerging infectious disease. Emerg Infect Dis.1996;2(3):192-199.

18. Pappagianis D, Vanderlip J, May B. Coccidioidomycosis naturally acquired by a monkey, Cercocebus atys, in Davis, California. Sabouraudia.1973;11(1):52-55.

19. Rosenberg DP, Gleiser CA, Carey KD. Spinal coccidioidomycosis in a baboon. J Am Vet Med Assoc.1984;185(11):1379-1381.

20. Shubitz LE, Butkiewicz CD, Dial SM, Lindan CP. Incidence of coccidioides infection among dogs residing in a region in which the organism is endemic. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;226(11):1846-1850.

21. Shubitz LF. Comparative aspects of coccidioidomycosis in animals and humans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:395-403.