Signalment:

Gross Description:

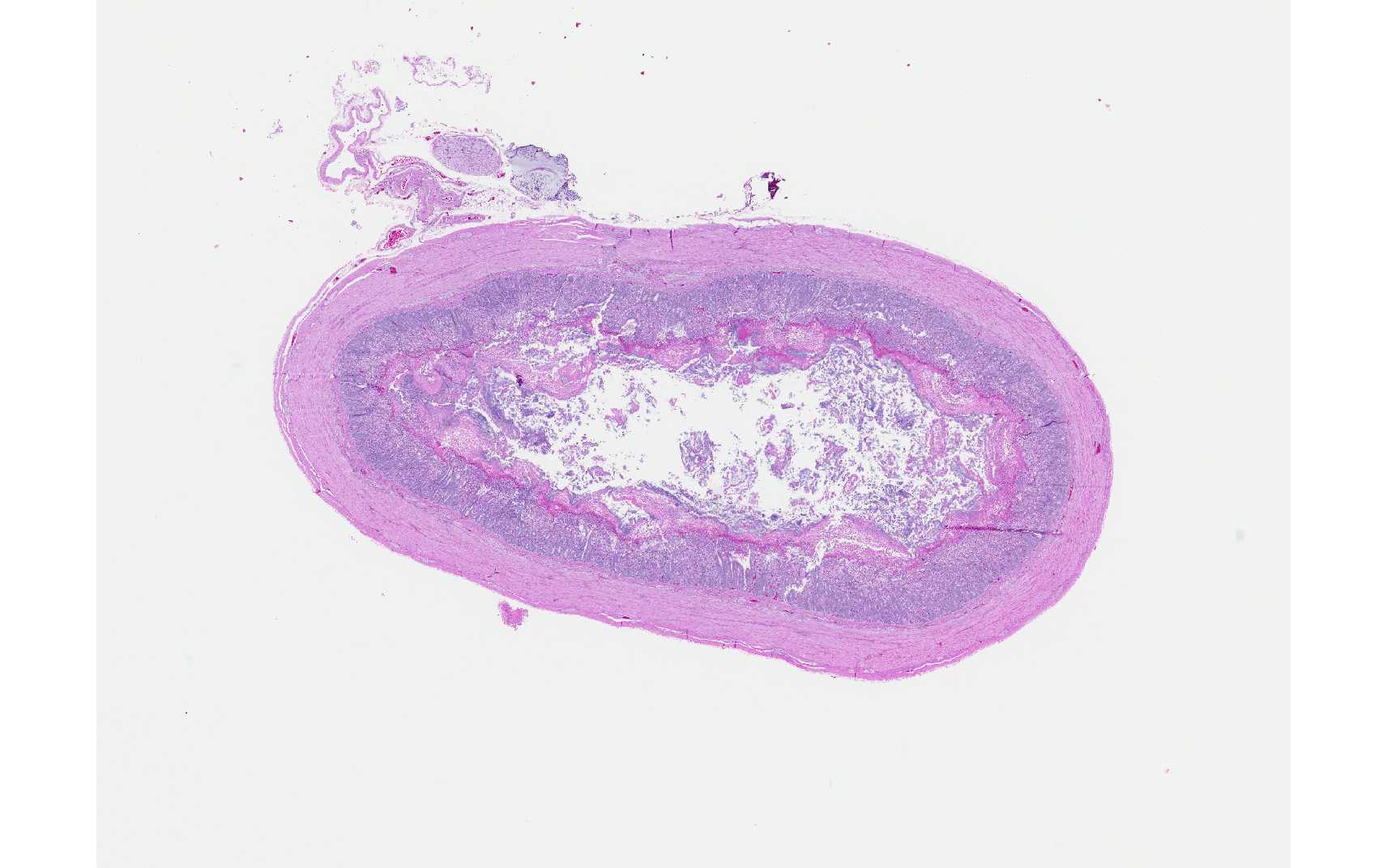

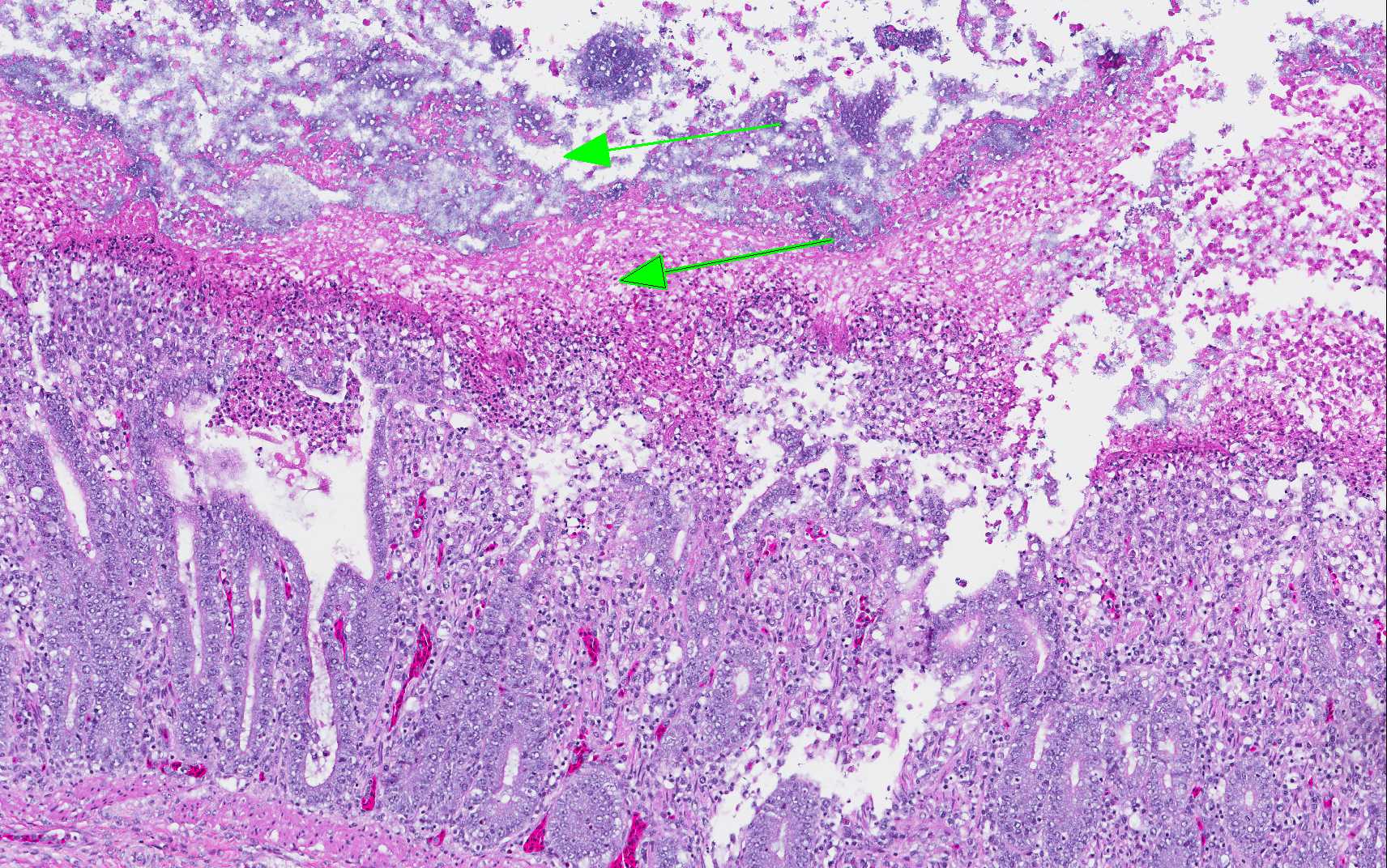

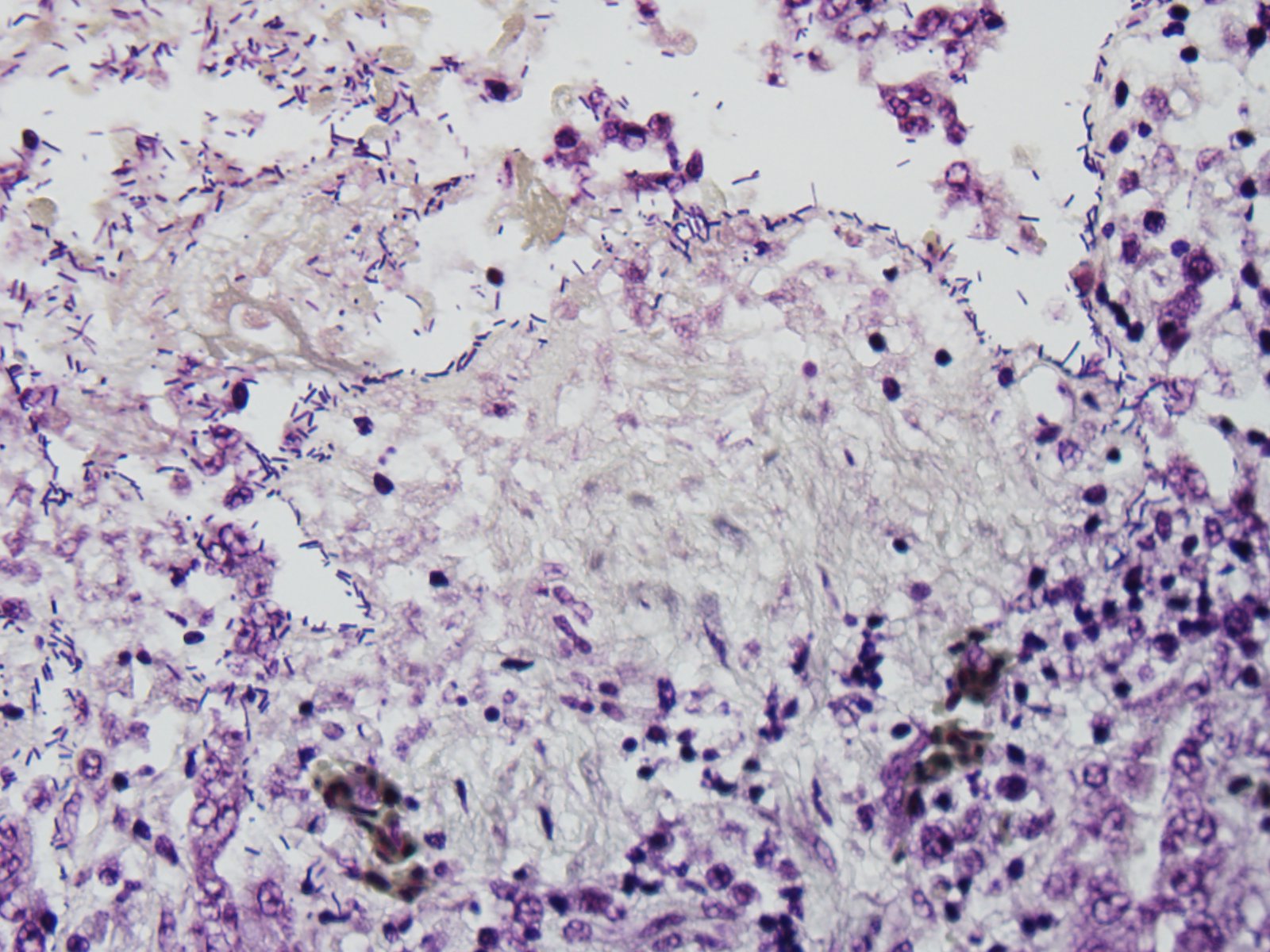

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

C. perfringens is normally found in the environment and is part of the normal flora of birds. Disease occurs following an alteration in the intestinal microflora or a condition that results in damage to the mucosa (coccidia, salmonella, ascarid larva, mycotoxins). Diets high in indigestible, water-soluble, non-starch polysaccharides (wheat, rye, oats, barley) are risk factors for the disease in birds.(3) The organic feed in this case may have contained some of these carbohydrates and would explain why only birds fed this diet were affected.

Necrotic enteritis usually manifests as an acute disease with a sudden increase in flock mortality. There is also a subclinical form of the disease in which birds have reduced weight gain and poor feed conversion ratios due to poor digestion and absorption from the damaged intestinal mucosa.(3) This bird was emaciated and may have had the subclinical form of the disease followed by the acute clinical disease terminally.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

A key element in the pathogenesis of C. perfringens induced NE in chickens is the pore-forming NetB toxin (which has some similarities to C. perfringens beta toxin). It creates a hole in the cell membrane that results in leakage of cell contents and cell death and is apparently a central factor in disease pathogenesis. Strains of C. perfringens positive for the netB gene also carry additional virulence genes for toxins, other nutritional/metabolic factors related to fitness, and adhesins, which contributes to their ability to proliferate rapidly and cause disease. It is suggested the NetB toxin is a key initiating factor in the pathogenesis of NE, and may actually target endothelial cells in the lamina propria and not the intestinal epithelium. Key initiating events include colonization of the intestinal mucosa and degradation of the mucous layer, which allows toxins access to the enterocytes.(2)

Histologic lesions are characterized by extensive mucosal necrosis which may extend into the submucosa or even the muscularis in severe cases. There is a sharp line of demarcation between necrotic and viable tissue and bacilli are seen trapped in fibrinonecrotic debris.(1) A key histologic feature in NE includes the presence of abundant large C. perfringens bacilli at the margin of the submucosa once the superficial mucosa has become necrotic and is sloughed, which may represent biofilm formation and be related to disease pathogenesis or progression.(2) Gross lesions are typically isolated to the small intestine, but may also be seen in the ceca. The intestine is thin-walled, gas-distended and filled with a dark brown, grey, and/or yellow-green fluid, while the mucosal surface is typically covered by a necrotic coagulum. Thickening of the intestinal wall may be seen in chronic cases and some affected chickens may develop cholangiohepatitis.

The differential diagnosis includes coccidiosis, which may preceed NE and can be differentiated by the presence of blood in the intestinal tract (which is not typically seen in cases of NE), and the presence of coccidial organisms. Ulcerative enteritis caused by C. coliseum and histomoniasis are other diagnostic considerations.(1)

References:

2. Prescott JF, Parreira VR, Mehdizadeh GI, Lepp D, Gong J. The pathogenesis of necrotic enteritis in chickens: What we know and what we need to know. Review. Avian Pathol. 2016; Jan26 Epub:1-21.

3. Timbermont L, Haesebrouck F, Ducatelle R, Van Immerseel F. Necrotic enteritis in broilers: an updated review on the pathogenesis. Avian Pathol. 2011; 40:341-347.

4. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infection. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:170.