CASE 4: N-864-18 (4153559-00)

Signalment:

Four-day-old Aberdeen Angus male calf, bovine (Bos taurus taurus)

History:

A male Angus calf was delivered by a heifer, without any abnormalities in the calving process. Initially the animal was clinically normal, and ingested colostrum and milk adequately; however, on the third day of life the calf started presenting clinical signs including anorexia, diarrhea, and apathy. The clinical picture rapidly progressed to persistent lateral recumbence and neurological manifestations characterized by nystagmus, teeth grinding, opisthotonus, and paddling movements. In addition, unilateral left hypopyon was observed. In the next day (fourth day of life, second day of clinical progression), euthanasia was elected due to the poor prognosis. The calf was referred from an extensive cow-calf operation with around two hundred dams located in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, southern Brazil. Two other newborn calves were reported to become ill in the comprehended period, one of which died; however, necropsy was not performed in these cases.

Gross Pathology:

The animal presented good body condition and a small amount of orange feces was observed adhered to the perianal area. Externally, the main visible abnormality consisted of accumulation of white material in the anterior chamber of the left eye (unilateral hypopyon). At the opening of the thoracic and abdominal cavities, multiple soft, white to yellow nodules (0.2-1.0 cm in diameter) were observed in the liver, spleen, kidneys, mesenteric lymph nodes, heart, and lungs. Cross sectioning of the cerebellum revealed a reddish, locally extensive, soft to friable, irregular area, effacing great part of the organ. Multifocal reddish circular areas ranging from 0.5 to 1.0 cm in diameter, similar to those described in the cerebellum, were also observed in the basal nuclei, thalamus, mesencephalon, and telencephalon. Cross sectioning of the left eye revealed anterior peripheral synechia, posterior synechia, diffuse white discoloration and thickening of the choroid, and accumulation of white, friable material in the anterior chamber (hypopyon).

Laboratory results:

Fresh liver and brain fragments were collected and inoculated in Sabouraud dextrose agar (Kasvi®), MacConkey agar (Kasvi®) and Blood agar base (Kasvi®) with 5% sheep blood. The plates were incubated aerobically at 37 °C. MacConkey and Sabouraud plates did not have any growth after 72 hours. In both blood agars (brain and liver), within 24 hours of incubation, the growth of white to gray, downy, and fluffy fungal colonies was observed. To identify the fungus, total DNA was extracted from these colonies, as previously described.2 The partial 18S rDNA was amplified by PCR reaction as described elsewhere,9 using the following primers: EukA-F: 5´-AACCTGGTTGATCCTGCCAGT-3´ EukA-R: 5´-GATCCWTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC-3´. PCR amplicons were analyzed by Sanger sequencing.

The generated sequences were compared using BLAST (NCBI database), and matched to Mortierella wolfii, showing 99% of identity in the 18S rDNA partial sequence. For confirmation of the identity of the fungus, a phylogenetic analysis was performed within the phylum Zygomycota. M. wolfii isolate was positioned in the Mortierellomycotina subphylum clade together with other M. wolfii sequences.2 Samples of blood serum, spleen, and lymph nodes were also submitted to the reverse transcription- PCR assay to identify the bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV);1 however, the results were negative for all tested samples.

Microscopic description:

Each submitted slide presents a section of cerebellum. The normal trilaminar cerebellar aspect has been nearly completely effaced by multifocal to coalescing areas of marked necrosis and neuropil rarefaction, which are seen both in the white and grey matter. These areas are associated with intense accumulation of necrotic cellular debris, fibrin deposition, hemorrhage, and marked inflammatory infiltrate of viable and degenerate neutrophils, foamy macrophages (gitter cells), lymphocytes, plasma cells and rare multinucleated giant cells. These inflammatory cells are present within necrotic areas, frequently markedly expanding Virchow-Robin spaces, as well as extending and severely expanding the adjacent leptomeninges.

Amidst the necrotic areas, marked multifocal fibrinoid necrosis and hyalinization of blood vessels are observed. Affected vessels present the wall markedly expanded by accumulation of amorphous proteinaceous material and inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils. In addition, marked multifocal thrombosis in commonly seen associated with these blood vessels.

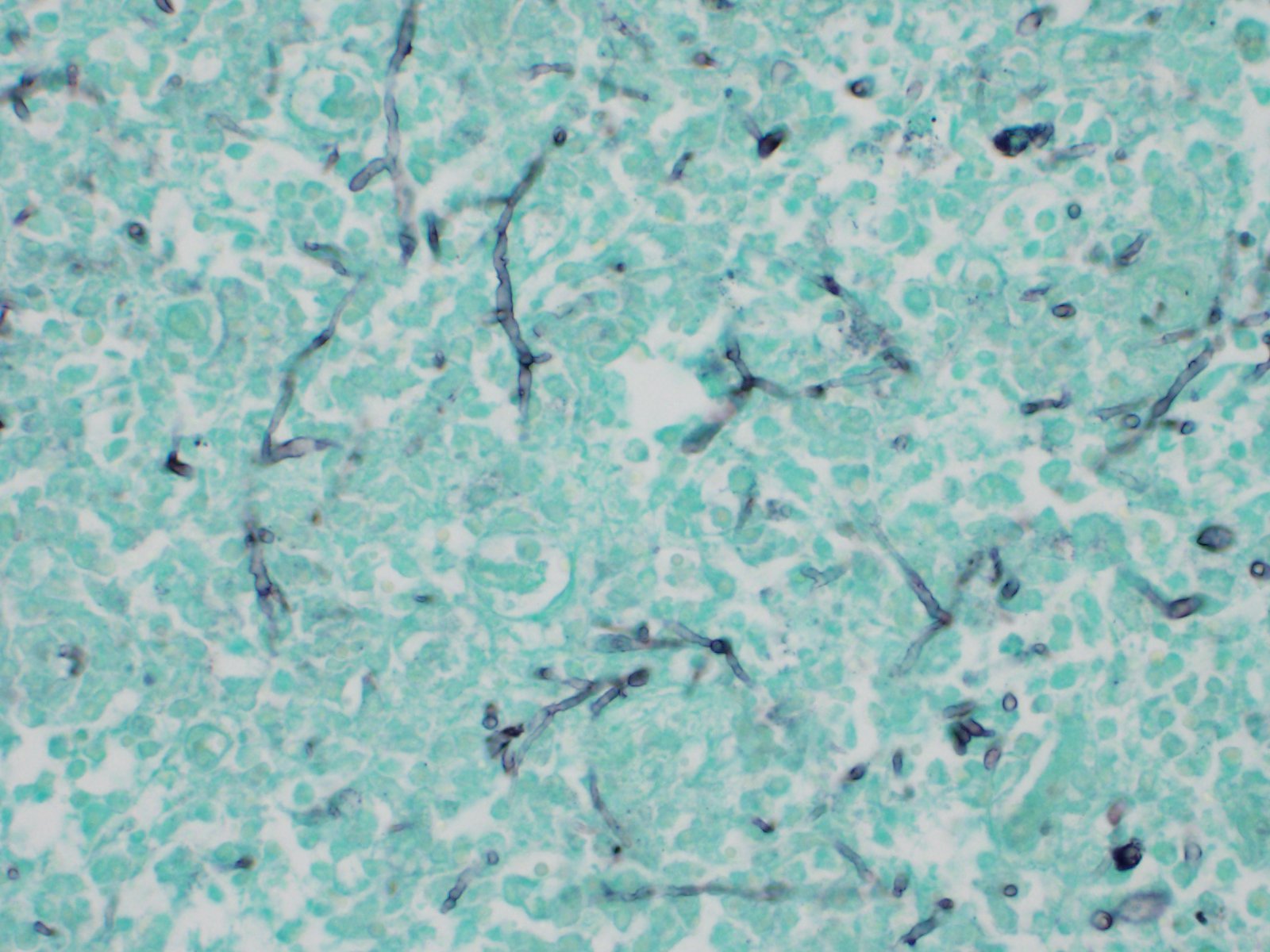

Numerous hyaline hyphae are observed intermixed with inflammation and necrotic areas. These fungal structures are large (3-8 ?m wide), present scarce septations, non-parallel walls, non-dichotomous branching, and occasionally show bulbous dilatations. Multifocally, numerous hyphae are also frequently observed surrounding as well as invading and expanding the wall of blood vessels, associated with the mentioned vascular changes. Fungal characteristics are highlighted with Grocott methenamine silver stain.

Some slides present sections of choroid plexus, in which multifocal, mild inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils is seen. In addition, similar multifocal areas of marked necrosis and inflammation associated with fungal hyphae were seen in several organs, including the liver, left eye, spleen, kidneys, heart, thyroids, adrenal glands, mesenteric lymph nodes, as well as other regions of the encephalon.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Necrotizing and pyogranulomatous meningoencephalitis, marked, multifocal to coalescing, subacute, associated with severe multifocal vasculitis, thrombosis and numerous fungal hyphae.

Lymphohistiocytic and neutrophilic choroid plexitis, subacute, mild, multifocal.

Contributor's comment:

Mortierella wolfii is a saprophytic fungus, which belongs to the zygomycetes class.6,11 This agent is found in the environment, including in spoiled feeds such as moldy silage and hay,7,11 however, it can also be found in the soil and pastures.7 Zygomycetes are often implicated as a cause of abortion in cattle,7 and M. wolfii is the most common agent in New Zealand, where it has been considered the causative agent of a condition named "distinctive mycotic abortion-pneumonia syndrome"3, though it rarely induces systemic disease in adult cattle6,11 or in neonatal calves.12 To the best of the author's knowledge, this is the first description of this condition affecting cattle of this age group outside Oceania.2

In this case, the alterations observed in the brain, as well as in several other organs, are associated with vascular lesions, and indicate a probable hematogenous dissemination of the fungus. Tropism of zygomycetes for blood vessels occurs through a process called angioinvasion. Hyphae have the ability to invade endothelial cells, gain access to the circulatory system, and spread to other parts of the body. The presence of infarcts, necrosis, and vasculitis are considered typical lesions that occur secondarily to the fungal invasion of the blood vessels,11,17 as observed in this case.

It is suggested that Mortierella infection may occur in utero.12,14 The fungus establishes a primary respiratory infection in the dam, enters the bloodstream and reaches the uterus, where it can induce acute metritis and placentitis, leading to abortion due to fetal hypoxia.11,14 Even though subacute or chronic fungal metritis and placentitis may allow fetal infection, calves are usually born alive and clinically normal, and may develop lesions and clinical disease a few days after calving,14 similar to what is described in this case. In older calves and adult cattle, disseminated mycoses may occur due to a primary gastrointestinal or respiratory infection.5

We highlight that the culture using blood agar base showed pure fungal growth, while no growth occurred in the Sabouraud agar, which is likely related to the tropism of M. wolfii. Moreover, the 18S rDNA partial sequencing and analysis was able to confirm the identity of the isolated fungus as M. wolfii, with 99% of identity in the matching BLAST search. Because of the presence of neurological clinical signs and hypopyon; bacterial septicemia is the main differential diagnosis of this case. This has been mostly observed in neonatal calves that did not ingest colostrum adequately, and this condition is predominantly associated with Escherichia coli infection.8 Infectious thrombotic meningo-encephalitis caused by Histophilus somni is characterized by similar gross lesions in the brain, however histological lesions are distinct.6,10

Furthermore, other fungi, especially Aspergillus spp. and zygomycetes, may cause similar lesions as those observed in this case, and the differential diagnosis should be done mainly through culture and molecular tests.6,11,14

Contributing Institution:

Faculdade de Veterinária

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul

Setor de Patologia Veterinária

http://www.ufrgs.br/patologia

JPC diagnosis:

Cerebellum: Meningoencephalitis, necrotizing and fibrinosuppurative, diffuse, acute, severe, with necrotizing vasculitis, thrombosis, hemorrhage, and numerous fungal hyphae, Aberdeen Angus, bovine.

JPC comment:

The contributor provides a succinct synopsis of Mortierella wolfii. As stated, these fungi exhibit angiotropism, leading to clotting of blood in vessels, and subsequent infarction and extensive necrosis of tissues, a trait shared among most zygomycetes.15 Mortierella spp, along with zygomyces of the Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, Absidia, and Mucor genera, are most often implicated in mycotic bovine abortion, gastrointestinal infections, ulcerative lesions and mesenteric lymphadenitis. It is also notable for causing respiratory, CNS, and visceral infection as a result of hematogenous dissemination. While they often cause no problems to carriers, stress from dietary changes, malnutrition, antibiotic use resulting to alteration of gastrointestinal flora, concurrent infections, recent parturition, or other physical trauma may increase the likelihood of infection.4

A recent, less common, presentation of mycotic ulcerative keratitis in a thoroughbred horse in Japan was shown to be due to Mortierella wolfii. In this case, the ventral two thirds of the right cornea were opaque with intercellular epithelial edema, with multifocal, punctate, gray opacities in the epithelium of the axial cornea and a superficial corneal ulcer. Direct and indirect pupillary light reflexes were normal, there was no aqueous flare in the anterior chamber, and no abnormalities were detected in the posterior segment. Cytologic evaluation of corneal scrapings is often useful in the diagnosis of keratomycosis, with nonseptate hyphae easily visualized.16

There are several characteristics that increase pathogenicity of some of the zygomycetes, and specifically those of Mucorales. They possess the ability to suppress IFN-l and RANTES (CCL5) in natural killer cells. They acquire iron through siderophores (iron chelators) and high-affinity iron permeases, and likely also extract iron from hemoglobin. Increased iron concentrations allow for rapid fungal growth, as well as impairing phagocyte function and decreasing IFN-l secretion (in a mouse model). In order to facilitate vascular invasion, Mucorales adhere to endothelial cells by binding host receptor GRP78 with ligand spore coat homolog (CotH) proteins, leading to endocytosis of the fungus.13

One interesting aspect of the contributor's laboratory analysis is that no growth in Sabouraud's agar was noted. Typically, Rhizopus spp, Rhizomucor spp, Absidia spp, Mucor spp, and Mortierella spp grow rapidly on Sabourd's agar at room temperature.4 Additional elucidation of the pathogenesis of Mortierella wolfii may provide insights into this finding.

References:

1. Bianchi MV, Konradt G, de Souza, SO, et al. Natural outbreak of BVDV-1d?induced mucosal disease lacking intestinal lesions. Vet Pathol. 2016;54(2):242?248.

2. Bianchi RM, Vielmo A, Schwertz CI, et al. Fatal systemic Mortierella wolfii infection in a neonatal calf in southern Brazil. Cienc Rural. 2020;50(1):1?5.

3. Carter ME, Cordes DO, di Menna ME, Hunter R. Fungi isolated from bovine mycotic abortion and pneumonia with special reference to Mortierella wolfii. Res Vet Sci. 1973;14:201?206.

4. Chengappa MM, Pohlman LM. Agents of Systemic Mycoses. In: eds. McVey DS, Kennedy M, Chengappa MM, Veterinary Microbiology, 3rd Ed. Ames, IA:John Wiley and Sons, Inc. 2013:342.

5. Chihaya Y, Matsukawa K, K Ohshima, et al. A pathological study of bovine alimentary mycosis. J Comp Pathol. 1992;107:195?206.

6. Curtis B, Hollinger C, Lim A, Kiupel M. Embolic mycotic encephalitis in a cow following Mortierella wolfii infection of a surgery site. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2017;29(5):725?728

7. Knudtson WU, Kirkbride CA. Fungi associated with bovine abortion in the Northern plains states (USA). J Vet Diagn Invest. 1992;4:181?185.

8. Konradt G, Bassuino DM, Prates KS, et al. Suppurative infectious diseases of the central nervous system in domestic ruminants. Pesq Vet Bras. 2017;7(8):820?828

9. Medlin L, Elwood HJ, Stickel S, Sogin, ML. The characterization of enzymatically amplified eukaryotic 16S-like rRNA-coding regions. Gene. 1988;71:491?499.

10. Momotani E, Yabuki Y, Miho H, Ishikawa Y, Yoshino T. Histopathological evaluation of disseminated intravascular coagulation in Haemophilus somnus infection in cattle. J Comp Pathol. 1985;95:15?23.

11. Munday JS, Laven RA, Orbell GMB, Pandey, SK. Meningoencephalitis in an adult cow due to Mortierella wolfii. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2006;18:619?622.

12. Munday JS, Wolfe AG, KE Lawrence, Pandey, SK. Disseminated Mortierella wolfii infection in a neonatal calf. N Z Vet J. 2010;58:62?63.

13. Petrikkos G, Tsioutis C. Recent Advances in the Pathogenesis of Mucormycoses. Clinical Therapeutics. 2018;40(6):894-902.

14. Vasconcelos DY, Grahn BH. Disseminated Rhizopus infection with ocular involvement in a calf. Vet Pathol. 1995;32:78?81.

15. Voigt K, Vaas L, Stielow B, de Hoog GS. The zygomycetes in a phylogenetic perspective. Persoonia. 2013;30:i-iv. doi:10.3767/003158513X666277

16. Wada S, Ode H, Hobo S, et al. Mortierella wolfii keratomycosis in a horse. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 2011;14(4):267-270.

17. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infections. In: Zachary JF. Pathologic basis of veterinary disease. 6th. St. Louis, Missouri, USA: Elsevier; 2017:132?241.