Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 17

January 31st, 2018

CASE II: 12-294 (JPC 4021148).

Signalment: Stillborn, male, Welsh-cross pony, Equus caballus, equine.

History: Animal presented for necropsy following stillbirth.

Gross Pathology: This male Welsh-cross pony fetus presented for necropsy to the Frederick Diagnostic Laboratory. The periocular and oral mucous membranes tissues were yellow and there was meconium pasted on the hair and skin (fetal distress). The subcutaneous tissues were discolored yellow (icterus) and there was marked subcutaneous edema in the intermandibular space (bottlejaw), at the thoracic inlet, and in the inguinal/femoral region. Additionally approximately 1L of clear yellow fluid was noted in the peritoneal cavity. The liver was markedly enlarged, rubbery pink/purple with rounded lobe margins. The kidneys were bilaterally brown and the adrenal glands both had multifocal acute cortical hemorrhages. The epicardium contained few, small (2-5mm) scattered hemorrhages in the left and right ventricular free walls and there was multifocal to coalescing, bright red subendocardial hemorrhages in both right and left ventricles extending into the myocardium.

Laboratory Results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.):

- Equine Herpes Virus FAT Lung POSITIVE; Liver POSITIVE

- Equine Viral Arteritis FAT Lung NEGATIVE

Microscopic Description:

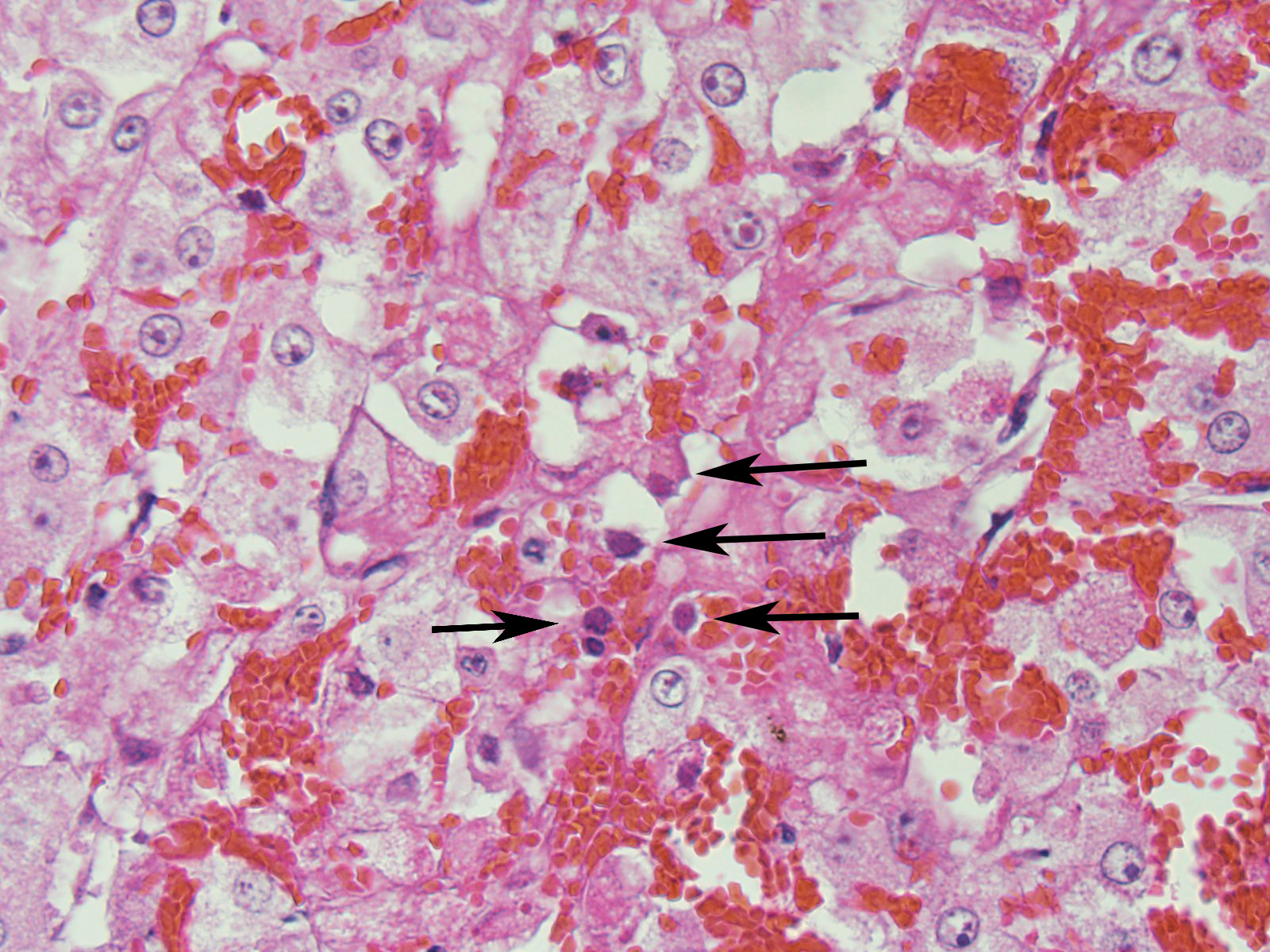

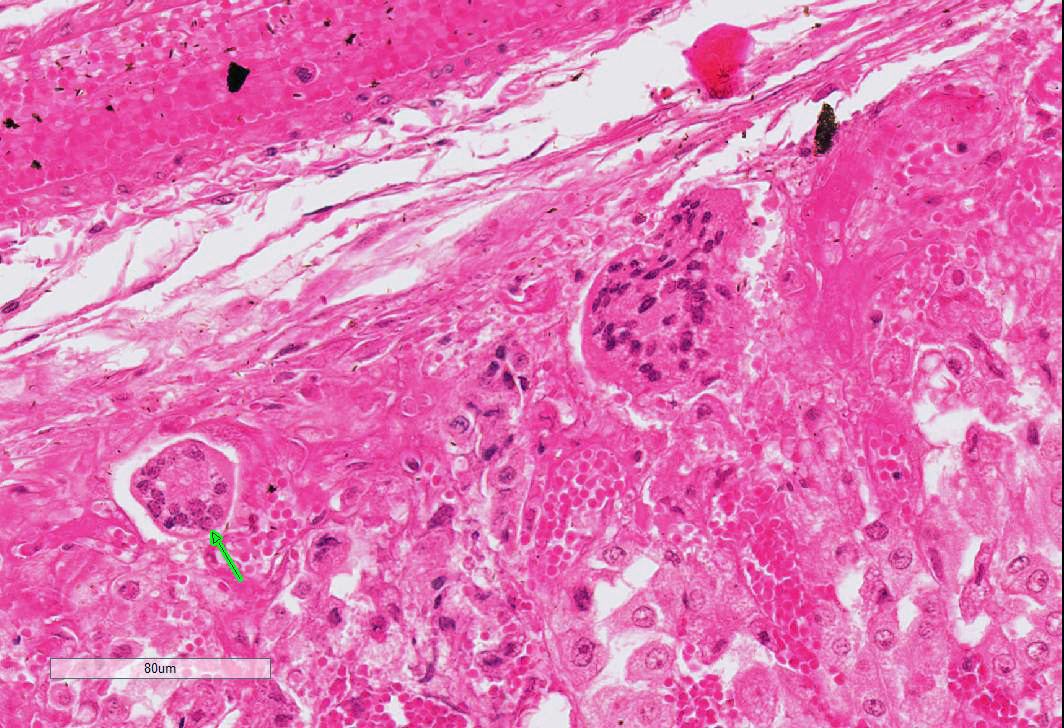

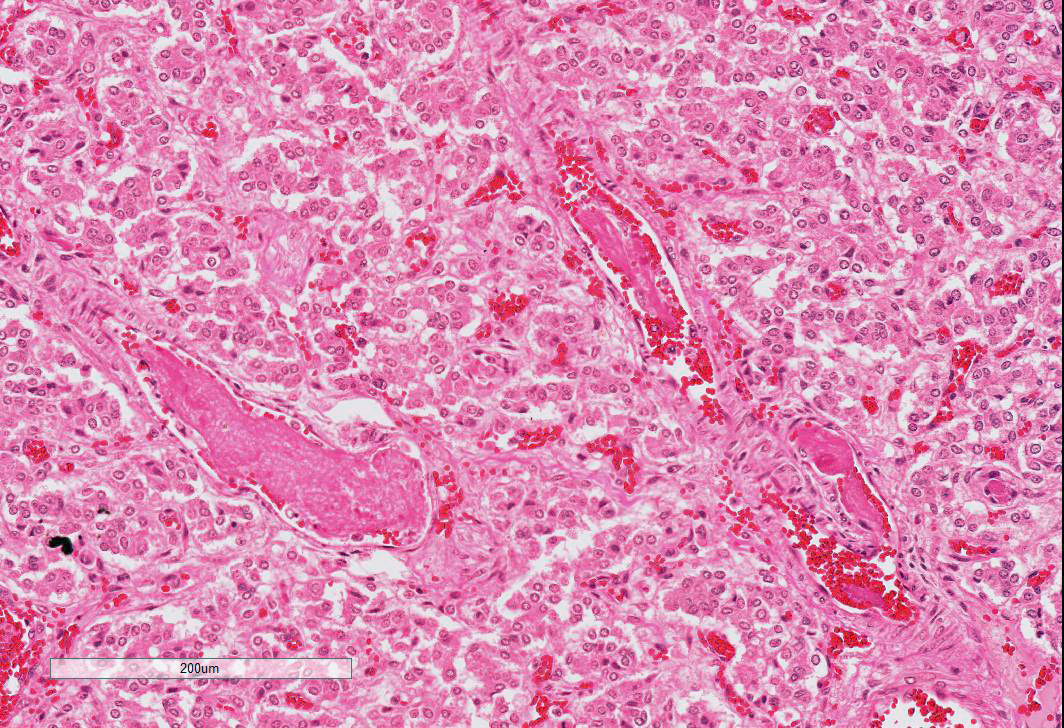

Adrenal gland: Primarily within the superficial cortex, there are multifocal to coalescing areas of necrosis and hemorrhage. Subcapsularly, there are numerous multinucleated synctial cells that are occasionally necrotic. Multifocally within cortical and synctial cells, there are 5-10 um eosinophilic intranuclear viral inclusion bodies that frequently peripheralize the chromatin. Multifocally occluding the sinusoids of both the cortex and the medulla, there are rare fibrin thrombi. The adjacent ganglion is essentially normal.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Adrenal gland: Cortical necrosis, multifocal with moderate cortical hemorrhage, subcapsular syncitiae, rare medullary sinusoidal thrombosis and eosinophilic, intranuclear viral inclusions

Contributor’s Comment: Equine herpesvirus type 1 (EHV-1) typically results in a multisystemic vasculitis which is almost invariably fatal in equine fetuses and neonates. The virus can be subdivided into two subtypes both of which cause neonatal disease and respiratory disease, however, the most common subtype isolated in aborted foals is subtype 1 and this type is also felt to be the only subtype which will result in the neurologic form of the disease. Abortion frequently occurs in animals that have been exposed to the disease at an earlier point, potentially as a mild respiratory form of the disease. The virus is transmitted to the foal via leukocytes within the bloodstream and subsequently to the placenta. Fetal death typically occurs at the point of a sudden abortion without the mare showing premonitory signs.9

Aborted fetuses have diagnostic pathological lesions which were observed in this case. Affected animals often have significant subcutaneous and fascial edema as well as both thoracic and abdominal effusions. Additionally, icterus is a common finding. Histopathological findings characteristically are multiorgan hemorrhagic necrosis with acidophilic intranuclear inclusions within many tissues, but specifically within the bronchiolar and alveolar epithelium.2,3,9

This case of adrenal necrosis and hemorrhage in association with systemic EHV-1 and peri-partum stress is also interesting in its microscopic presentation which is similar to that seen in cases of endotoxic shock in humans and certain domestic species.4 These instances are variably described in the literature as the Waterhouse-Fredrickson (Friderichsen) syndrome specific to the adrenal gland or in more general terms as the Shwartzman reaction in which endotoxic shock during late gestation results in multiorgan thrombosis and hemorrhage. The former syndrome has been reported as associated with endotoxin induced adrenocortical necrosis and hemorrhage which then causes adrenal insufficiency.6 While the latter is used as a model for endotoxin induced disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).8

The Shwartzman phenomenon was described in the 1940s and1950s in humans relating to multi-organ infarction secondary to septic shock and endotoxin. Studies examining acute and severe hemorrhagic necrosis of the adrenal in rabbits used intravenous injection of endotoxin following pretreatment with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).5 The resultant pathological changes occurred primarily in the zona fasciculata of the adrenal cortex and mimicked the Shwartzman reaction. Studies of localized Shwartzman reaction has been shown to be due to massive releases of TNF-α by IFN-γ-activated macrophages, and results in microthrombi throughout the vasculature. While this particular case of abortion is theorized to be due to the effects of EHV-1 and not one of endotoxin related septic shock, the fetal stress associated with systemic equine herpesvirus infection likely resulted in a significant ACTH and substantial cortisol release with subsequent adrenal insufficiency. This priming by ACTH may have created a histopathological picture similar to that seen with the Shwartzman reaction in humans and the Waterhouse-Fredrickson syndrome described in septic calves and in baboons.1,4 Interestingly, there is a report of fatal cytomegalovirus associated adrenal insufficiency in an immunocompromised human receiving steroid therapy in which histopathological examination of the adrenal glands noted a necrotizing adrenalitis with adrenocortical hemorrhage and intranuclear viral inclusions consistent with cytomegalovirus.10

This case and its associated photographs were generously contributed by Dr. Virginia Pierce, Director of the Frederick Diagnostic Laboratory.

JPC Diagnosis: Adrenal gland, cortex: Adrenalitis, necrohemorrhagic, multifocal to coalescing, moderate with intranuclear viral inclusions, viral syncytia, and capsular, cortical, and medullary thrombi, multifocal, moderate, Welsh-cross pony (Equus caballus), equine.

Conference Comment: Viral infections have been postulated to result in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) by three mechanisms: viral or antiplatelet antibody-mediated platelet aggregation; directly by causing endothelial damage (the most likely mechanism in this case); or immune complex formation inducing activation of Hageman factor (factor XII). Hageman factor, the initiator of the intrinsic coagulation cascade, simultaneously converts plasminogen to plasmin which cleaves fibrinogen and fibrin to yield fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products (FDPs). These FDPs inhibit thrombin activity, fibrin polymerization, and platelet aggregation. Under normal circumstances, these two processes (coagulation and fibrinolysis) exist in equilibrium to limit thrombosis. Clinical manifestations of DIC include: generalized Schwartzman-like reaction (GSR); hemorrhagic adrenal necrosis (Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome); microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MHA); acrocyanosis and gangrene; or hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS).7

The generalized Schwartzman-like reaction is characterized by bilateral hemorrhagic renal cortical necrosis which can cause oliguric renal failure especially in septicemic postpartum cows. Likewise, Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome, causes hemorrhagic adrenal necrosis in septicemic calves. MHA is a result of intravascular fragmentation of erythrocytes also commonly seen in septicemic calves which frequently also exhibit acrocyanosis and gangrene of the distal extremities. Finally, HUS occurs when disseminated coagulation is combined with acute renal failure. This syndrome is well documented in humans, and has also been documented in Greyhound dogs with a condition colorfully named “Alabama rot” in which there is idiopathic cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy.7

Microscopically, animals in DIC have microthrombi in numerous organs, but are most easily detected in cerebral capillaries, renal glomeruli, adrenals, lungs, and myocardium. Generally, microthrombi are classified as hyaline thrombi (composed of fibrin), granular thrombi (composed of platelets), or hyaline globules/”shock bodies” (composed of FDPs). In cases with suspected DIC a prompt postmortem examination is imperative as fibrinolysis continues after death and most microthrombi will be lysed within 3 hours. Special stains for microthrombi include: Martius-scarlet-blue which stains fibrin red, or phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin (PTAH) which stains fibrin purple. Unfortunately, these stains only identify polymerized fibrin, however, fibrin strands can be identified in small vessels on H&E that often contain entrapped fragmented red blood cells, termed schistocytes, which serves as an indirect indicator of DIC.7

Conference attendees enthusiastically discussed the contributor’s suggestion that the necrosis and hemorrhage in the adrenal was a result of the Schwartzman reaction or Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome. However, as endotheliotropism and vascular thrombosis is well-documented in equine herpesvirus-1 infections, were unable to ascribe the lesions in the adrenal to other concurrent conditions in the absence of a more extensive clinical history or sections of other target tissues for these alternate possibilities.

Contributing Institution:Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute (AFRRI)

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS)

www.afrri.usuhs.mil

References:

- Cary M, Kosanke S, White G. Spontaneous Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome in a gang-housed baboon. J Med Primatol. 2001;30:185-187.

- Del Piero F, Wilkins PA, Timoney PJ, Kadushin J,Vogelbacker H, Lee JW, Berkowitz SJ, La Perle KMD. Fatal nonneurological EHV-1 infection in a yearling filly. Vet Pathol. 2000;37:672–676.

- Hamir AN, Vaala W, Heyer G, Moser G. Disseminated equine herpesvirus-1 infection in a two-year-old filly. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1994;6:493-496

- Hoffmann R. Adrenal lesions in calves dying from endotoxin shock, with special reference to the Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome. J Comp Path. 1977;87:231-239.

- Levin J, Cluff LE. Endotoxemia and adrenal hemorrhage: a mechanism for the Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome. J Exp Med. 1965;121:247–260.

- Maitra A. The endocrine system. In: Kumar V, Abbas A, Fausto N and Aster JC eds. Robbins and Cotran: Pathological Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders. 2010:1155.

- Robinson WF, Robinson NA. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie, MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th Vol. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:64-66.

- Rosenberg HF. The Shwartzman reaction repealed. J Leuk Biol. 2007;81:623-624.

- Schlafer DH, Miller RB. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 3. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:532-534.

- Uno K, Konishi M, Yoshimoto E, Kasahara K, Mori K, Maeda K, Ishida E, Konishi N, Murakawa K, Mikasa K. Fatal cytomegalovirus-associated adrenal insufficiency in an AIDS patient receiving corticosteroid therapy. Intern Med. 2007;46:617-620.