Signalment:

There was an episodic fever most apparent during morning and evening associated with an increase in his coughing and regurgitation episodes. The referring veterinarian sent out ANA, ACH receptor, and T4 titers. The ANA was positive at 1:50 and the other results are not available. Thoracic radiographs were taken and an initial diagnosis of megaesophagus was made. An endoscopy was performed and some degrees of esophageal and gastric mucosal scarring were detected. The dog was started by the referring veterinarian on antibiotics, antacids and gastric protectants and then transferred to the Foster Hospital for Small Animals at the Tufts University Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine.

On initial physical exam at Tufts the animal was depressed and gagging on palpation of his trachea. There were harsh lung sounds dorsally and bilaterally. Thoracic radiographs showed patchy interstitial to alveolar lung pattern in the right lung lobes and left cranial lung lobe, consistent with aspiration pneumonia. The initial therapy at Tufts included IV fluids, antibiotics and Vitamin E and Selenium. A presumptive diagnosis of polymyositis was made and due to the overall poor prognosis and rising expenses the owner elected euthanasia and an autopsy was performed. Muscle biopsies were submitted to the neuromuscular laboratory at UC Davis.

Gross Description:

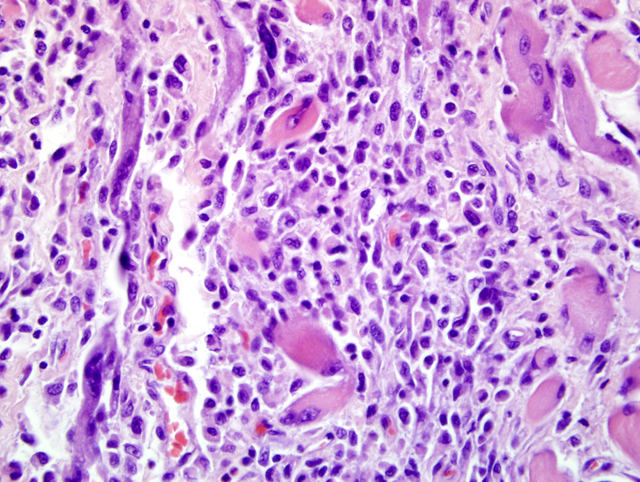

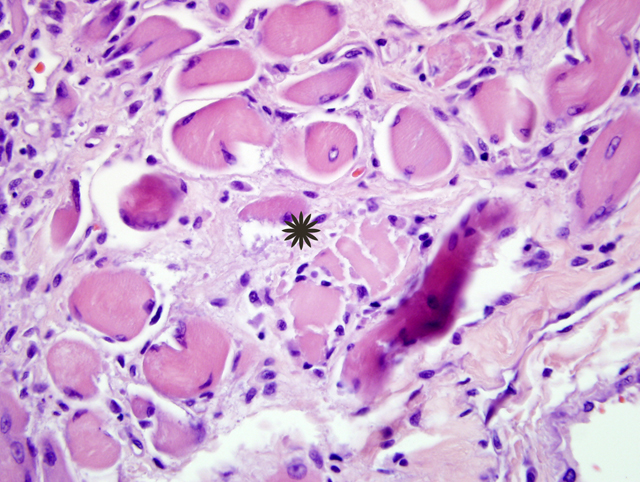

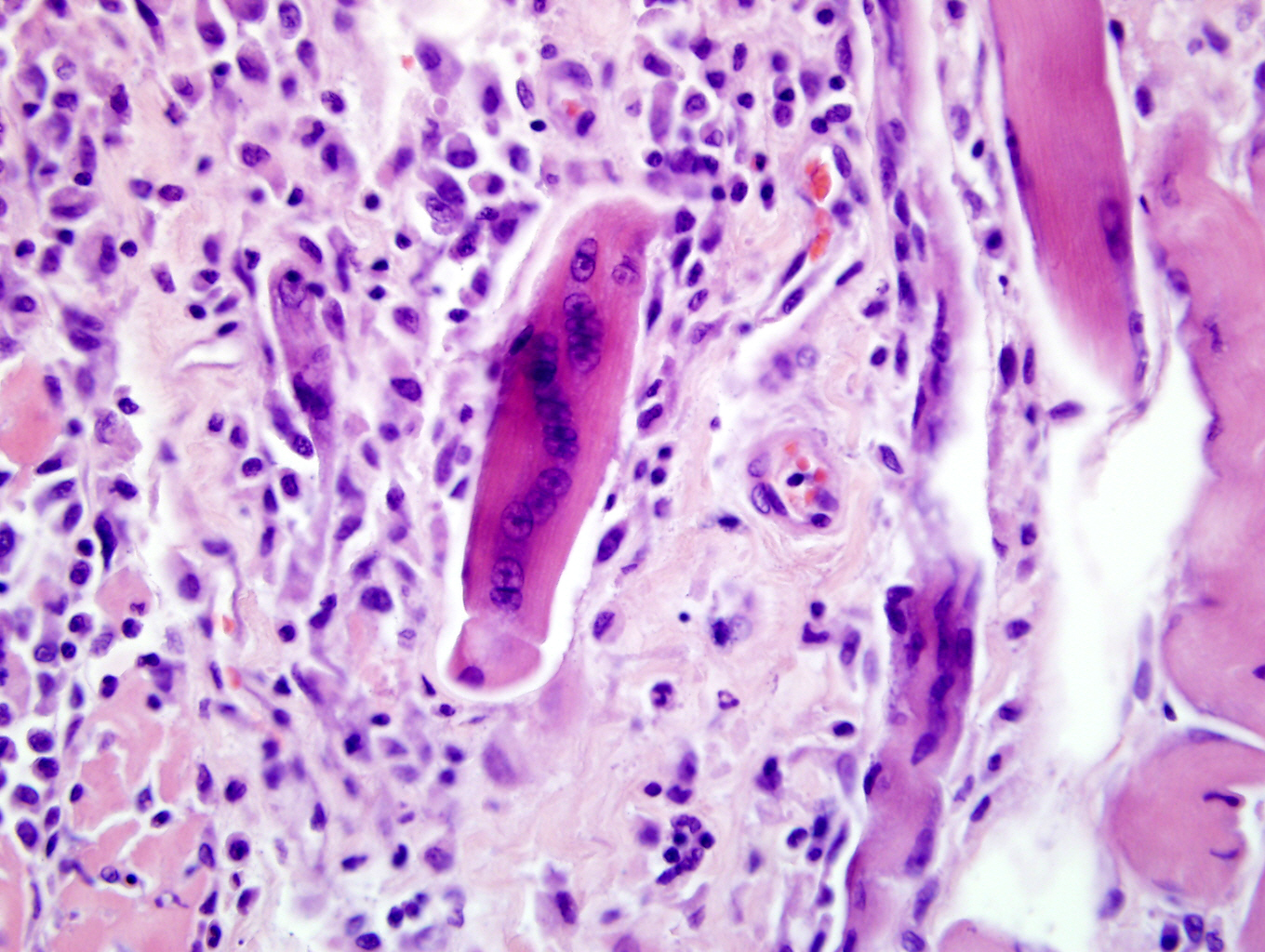

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Taurine: Plasma 19 nmol/l (normal values: 60-120)

Whole blood: 212 nmol/l (normal values: 300-600)

UA: Specific gravity (1.017)

Toxoplasma and neospora titers cancelled

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Inflammatory myopathies are a group of disorders characterized by non suppurative inflammation of skeletal muscles. Polymyositis is an immune-mediated, generalized skeletal muscle disorder characterized by muscular weakness, muscular atrophy, elevated serum concentration of creatine kinase, abnormal electromyography, negative serologic tests for infectious disease and lymphocytic infiltrate.4 Some forms of generalized myositis are associated with protozoal, rickettsial or bacterial infections.1 In human medicine and in few veterinary medicine cases, inflammatory myopathies have been associated with malignant neoplasia.2,6

Some inflammatory myopathies can be localized to particular groups of muscles such as the masticatory muscles15 and extraocular muscles.3 Such particular distributions are likely related to molecular characteristics of particular muscle groups. Masticatory muscles myositis for example affects all muscles innervated by the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (masseter, temporalis, pterygoids, tensor tympani and tensor veli palatine muscles) and is characterized by clinical signs such as jaw pain, inability to open the jaw and masticatory muscles atrophy. Masticatory muscles contain a distinctive muscle fiber, type 2M, which is biochemically and histocemically different from the muscle fibers contained within other skeletal muscles.15 Serum antibody titer for type 2M fibers is negative in extraocular myositis. The targeting of specific muscles in the current case suggests that these muscles may be distinct in some way from other skeletal muscle in the body.Â

Inflammatory polymyositis has been most thoroughly reported in veterinary medicine in Collies, Shetland sheepdogs and Newfoundlands, and it seems to be related to a generalized immune-mediated disorder.9 The association of inflammatory myositis with malignant neoplasia in dog has not been completely demonstrated, while it in human medicine it is commonly reported.2

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Generally, the muscles affected in MMM are specific to the muscles of mastication and spare the extraocular, esophageal, and limb muscles. In addition to autoantibodies against type 2M fibers, autoantibodies against myositigen, a masticatory muscle variant of the myosin binding protein C family, has been identified in cases of MMM.18 The cellular infiltrate in cases of MMM has some distinct differences between those seen in other types of inflammatory myopathies. In MMM, B-cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages are seen in greater numbers than T-cells, and the CD4+ T cells are seen in greater numbers than the CD8+ T cells.14,16

In polymyositis (PM), B cells are not a prominent feature, while CD8+ T cells are present in great numbers than CD4+ T cell. Both MHC class I and class II antigens are upregulated in cases of PM as well as MMM.12,14,16 In the Boxer and Newfoundland breeds, a sarcolemma-specific autoantibody has been identified in some dogs with PM. In general, dogs with PM will not have autoantibodies against type 2M fibers, although there have rare reports of on overlap syndrome in which dogs will have features of both PM and MMM.4,15

Extraocular myositis is an inflammatory condition restricted to the extraocular muscles; Golden retrievers may be more susceptible. Bilateral exophthalmos due to swelling of the extraocular muscles may be the only clinical sign, and may resemble the acute form of MMM.3, 16

Dermatomyositis is a breed-related (Collies, Shetland sheepdogs), autoimmune disorder of skeletal muscle, skin, and the vasculature.5,10,11,16,17 A perifascicular pattern of muscle fiber atrophy is considered a characteristic component of this disease.8,16 Cutaneous lesions are characterized by mild, perifollicular, mixed inflammation with follicular atrophy, follicular basal cell degeneration to the level of the isthmus, ulceration, crusting, smudging of the dermal collagen, and occasional vesiculations.7,13

References:

2. Buchbinder R, Hill CL: Malignancy in patients with inflammatory myopathy. Curr Rheumatol Rep 4:415-426, 2002

3. Carpenter J, Schmidt G, Moore F, Albert DM, Abrams KL, Elner VM: Canine bilateral extraocular polymyositis. Vet Pathol 26:510-512, 1989

4. Evans J, Levesque D, Shelton DG: Canine inflammatory myopathies: A clinicopathologic review of 200 cases. J Vet Intern Med 18:679-691, 2004

5. Ferguson EA, Cerundolo R, Lloyd DH, Rest J, Cappello R: Dermatomyositis in five Shetland sheepdogs in the United Kengdom. Vet Rec 146:214-217, 2000

6. Griffiths IR, Duncan ID, McQueen A: Neuromuscular disease in dogs: Some aspects of its investigation and diagnosis. J Small Anim Practice 14:533-554, 1973

7. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK: Interface diseases of the dermal-epidermal junction. In: Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 2nd ed., p49-52. Blackwell Science Ltd., Ames, IA, 2005

8. Hargis AM, Haupt KH, Hegreberg GA, Prieur DJ, Moore MP: Familial canine dermatomyositis: initial characterization of the cutaneous and muscular lesions. Am J Pathol 116:234-244, 1984

9. Hargis AM, Haupt K, Prieur DJ, Moore MP: A skin disorder in three Shetland Sheepdogs: Comparison with familial canine dermatomyositis of collies. Compend Cont Ed 7:306-315, 1985

10. Hargis AM, Prieur DJ, Haupt KH, Collier JJ, Evermann JF, Ladiges WG: Postmortem findings in four litters of dogs with familial canine dermatomyositis. Am J Pathol 123:480-496, 1986

11. Haupt KH, Prieur DJ, Moore MP, Hargis AM, Hegreberg GA, Gavin PR, Johnson RS: Familial canine dermatomyositis: clinical, electrodiagnostic, and genetic studies. Am J Vet Res 46:1861-1869, 1985

12. Morita T, Shimada A, Yashiro S, Takeuchi T, Hikasa Y, Okamoto Y, Mabuchi Y: Myofiber expression of class I major histocompatibility complex accompanied by CD8+ T-cell-associated myofiber injury in a case of canine polymyositis. Vet Pathol 39:512-515, 2002

13. Podell M: Inflammatory myopathies. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 32:147-167, 2002

14. Pumarola M, Moore PF, Shelton GD: Canine inflammatory myopathy: analysis of cellular infiltrates. Muscle Nerve 29:782-789, 2004

15. Shelton GD, Cardinet GH III, Bandmam E, Cuddon P: Fiber type-specific antibodies in a dog with eosinophilic myositis. Muscle Nerve 8:783-790, 1985

16. Shelton GD: From dog to man: the broad spectrum of inflammatory myopathies. Neuromuscul Disord 17:663-670, 2007

17. White SD, Shelton GD, Sisson A, McPherron M, Rosychuk RA, Olson PJ: Dermatomyositis in an adult Pembroke Welsh corgi. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 28:398-401, 1992

18. Wu X, Li Z, Brooks R, Komives EA, Torpey JW, Engvall E, Gonias SL, Shelton GD: Autoantibodies in canine masticatory muscle myositis recognize a novel myosin binding protein-C family member. J Immunol 179:4939-4944, 2007