Signalment:

Gross Description:

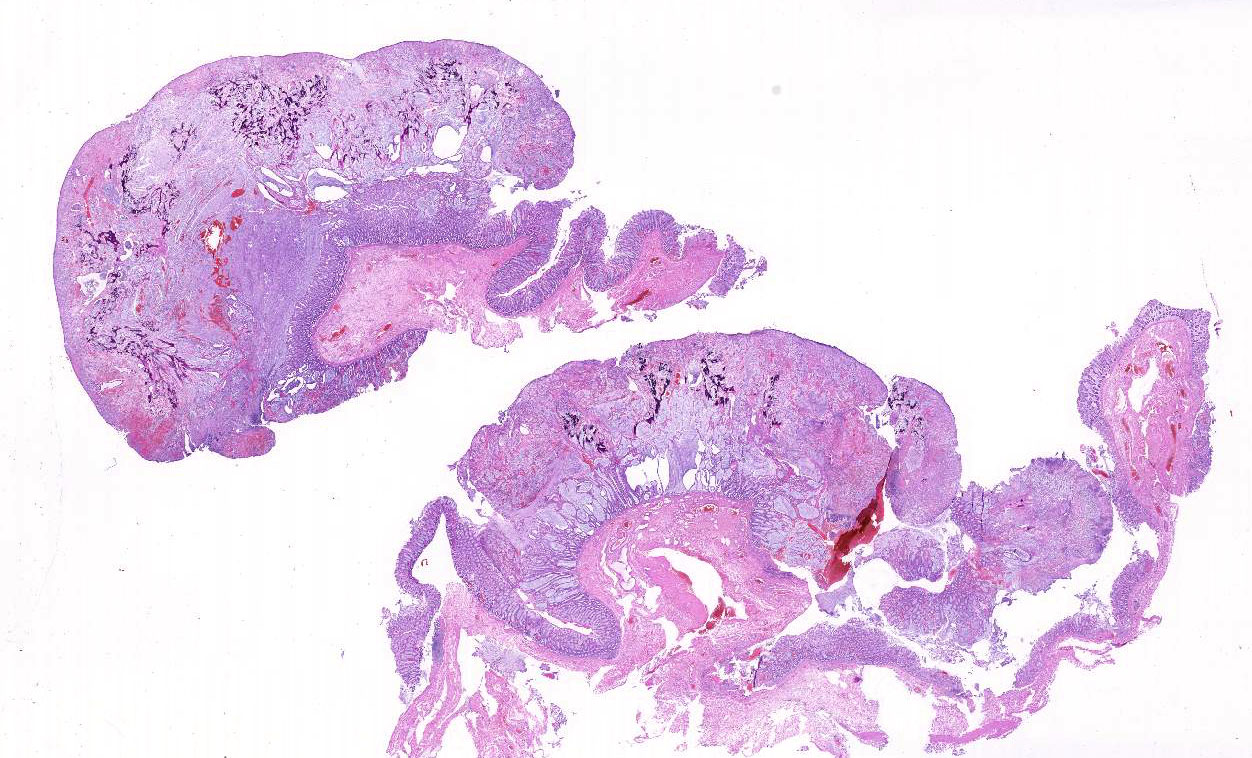

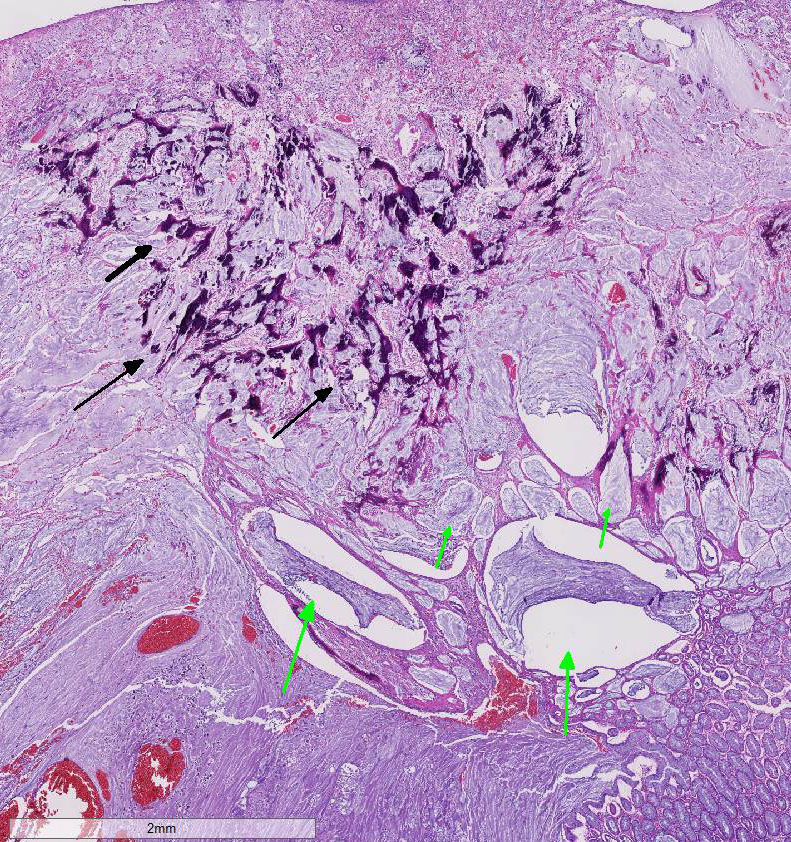

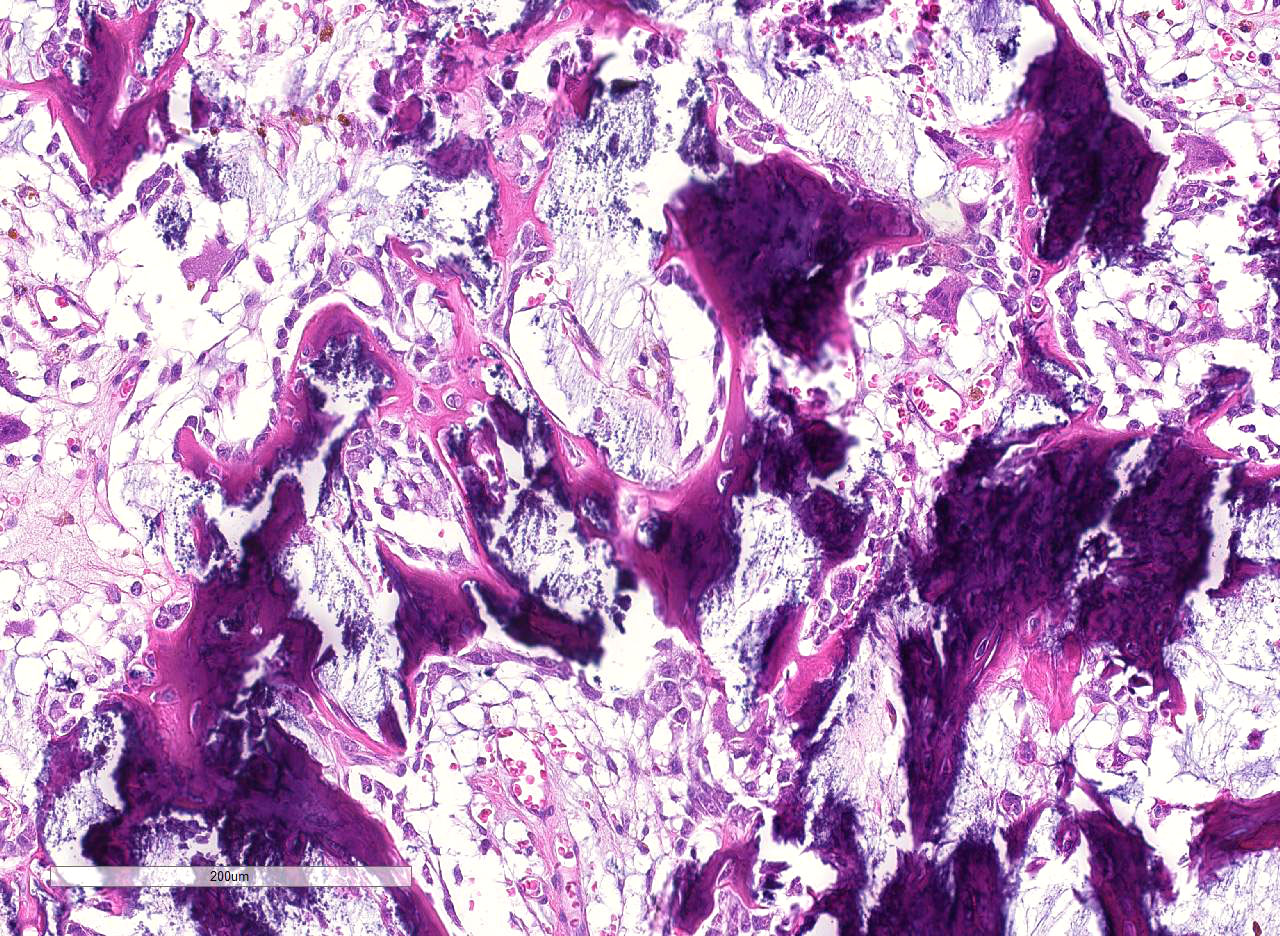

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In comparisons based on epithelial composition, the polyps displayed a thickened mucosa containing increased goblet cells, dilated crypts filled with a large amount of mucus, and mild inflammatory infiltration (mainly lymphocytes and macrophages) in the early stage.8 In later stages, leukocyte infiltration was more severe and consisted of mostly neutrophils and macrophages. Additionally, interstitial mucus accumulation, granulation tissue, and occasional osteoid formation were seen.8 In this case, predominant neutrophil infiltration, interstitial mucus accumulation, granulation tissue and osteoid formation were observed in the polyp; therefore, the lesion is comparable to that in late stage.

Although the pathogenesis remains unclear, some studies suggested that the arachidonic acid cascade, increased IL-8 production in macrophages, dysregulation of toll-like receptors and proinflammatory cytokines, and IL-17A upregulation in T cells are associated with the lesion formation.2,6,7 Additionally, 80% of cases responded to immunosuppressive therapy with prednisolone and cyclosporine.5 These findings indicate that inflammatory polyp of miniature dachshunds is an immunemediated disease. However, Igarashi et al reported that two cases developed adenomas secondary to inflammatory colorectal polyps during long-term medical therapy.4 Further investigations are required to elucidate the pathogenesis, oncogenesis, and prognosis in inflammatory polyps of miniature dachshunds.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

In a recent study by Uchida et al. published in Veterinary Pathology, they classify IPMD into early (stage 1) and late (stages 2 and 3) lesions based on the histopathology of the mucosal epithelial components and inflammatory cells present.8 In addition, they use immunohistochemistry to distinguish inflammatory polyps from neoplastic cells of adenomas and adenocarcinomas using cytokeratin 20 (CK20) and beta-catenin. Normally, intestinal goblet cells and enterocytes are strongly immunopositive for CK20. The markedly hyperplastic goblet cells, which is a key histologic feature of IPMD, are also strongly immunopositive for CK20, while neoplastic cells of adenomas and adenocarcinomas were immunonegative. This indicates that inflammatory polyps are a proliferation of well-differentiated epithelial tissue and non-neoplastic. The authors also demonstrate that IPMD expressed only intracytoplasmic betacatenin, while neoplastic cells of adenomas and adenocarcinomas expressed both intracytoplasmic and intranuclear betacatenin.8 There have been reports of dogs with later stage (stage 3) IPMD developing rectal adenomas secondary to neoplastic transformation.5 Chronic inflammation and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines can induce mutations in oncogene and tumor suppressor genes. In humans, the connection between chronic inflammatory bowel disease and development of both inflammatory polyps and colorectal carcinoma is well established.5 Aberrant activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway occurs in the vast majority of colorectal cancers in humans and dogs and likely plays a role in neoplastic transformation of late stage IPMD. 5,8 Inflammatory colorectal polyps are typically treated with immunosuppressive therapy and endoscope guided polypectomy.1,5,8 Unfortunately, recurrence after polypectomy is common. Recent research suggests that dysbiosis of the gastrointestinal tract is associated with IPMD and may be a potential future therapeutic target.3

References:

2. Igarashi H, Ohno K, Maeda S, et al. Expression profiling of pattern recognition receptors and selected cytokines in miniature dachshunds with inflammatory colorectal polyps. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2014; 159(1-2):1-10.

3. Igarashi H, Ohno K, Horigome A. Fecal dysbiosis in miniature dachshunds with inflammatory colorectal polyps. Res Vet Sci. 2016; 105:41-46.

4. Igarashi H, Ohno K, Ohmi A, et al. Polypoid adenomas secondary to inflammatory colorectal polyps in 2 miniature dachshunds. J Vet Med Sci. 2013; 75(4):535-538.

5. Ohmi A, Tsukamoto A, Ohno K, et al. A retrospective study of inflammatory colorectal polyps in miniature dachshunds. J Vet Med Sci. 2012; 74(1):59-64.

6. Ohta H, Takada K, Torisu S, et al. Expression of CD4+ T cell cytokine genes in the colorectal mucosa of inflammatory colorectal polyps in miniature dachshunds. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2013; 155(4):259- 263.

7. Tamura Y, Ohta H, Torisu S, et al. Markedly increased expression of interleukin-8 in the colorectal mucosa of inflammatory colorectal polyps in miniature dachshunds. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2013;156(1-2):32-42.

8. Uchida E, Chambers JK, Nakashima K, et al. Pathologic features of colorectal inflammatory polyps in miniature dachshunds. Vet Pathol. 2016; 53(4):833-839.