CASE 2: MW19-0351 (4152807-00)

Signalment:

6 year old, male castrated, Arabian cross, Equus caballus, equine

History:

A 6-year-old Arabian gelding presented initially with a history of reduced appetite, and low-grade fever. CBC revealed anemia and leukopenia and chemistry revealed azotemia, hypoglobulinemia, hyperphosphatemia and hyperkalemia. Urinalysis was in the isosthenuric range indicating renal failure. Ultimately, the patient became depressed and tachychardic, and then had a neurologic episode that consisted of seizure, recumbency, nystagmus from which he never recovered. Due to the poor prognosis, euthanasia was elected.

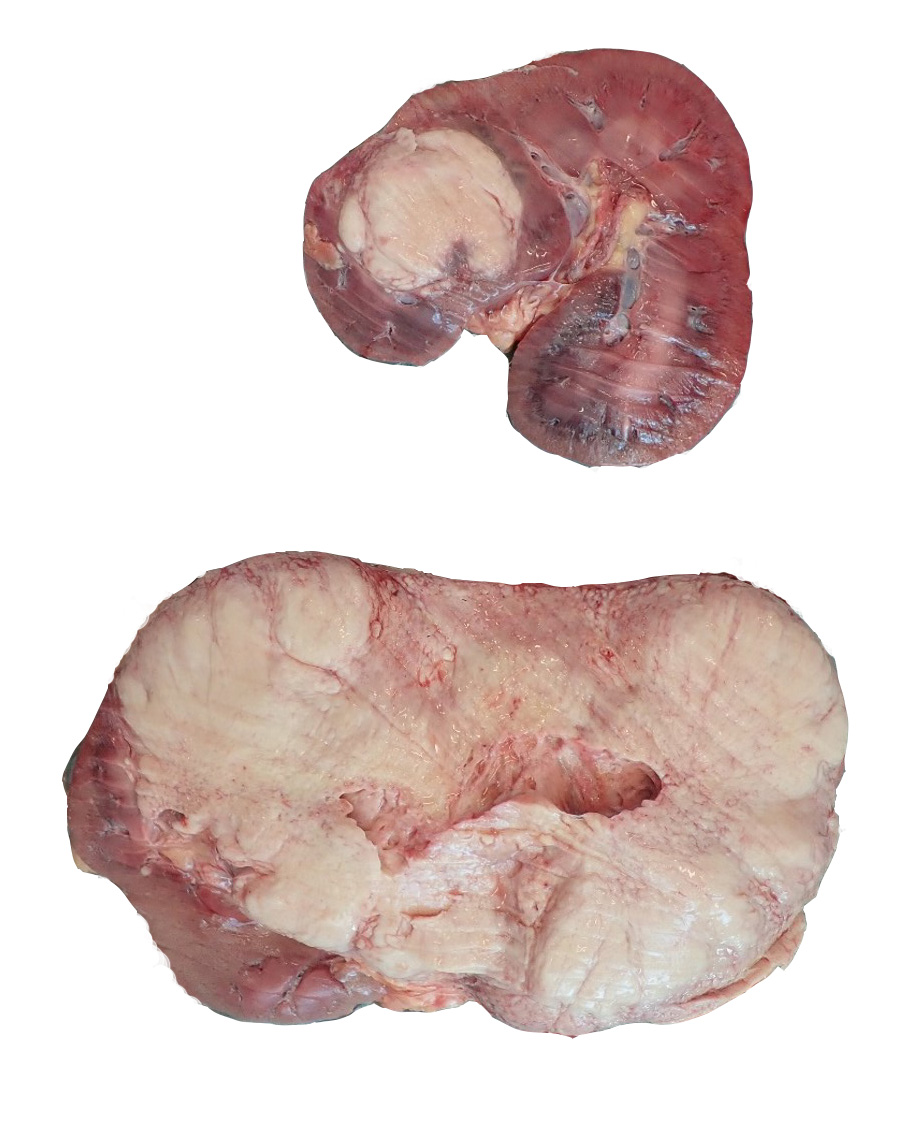

Gross Pathology:

The carcass was in fair body condition and good postmortem condition. The left kidney was severely enlarged, weighing 7.15 kg. On cross section, approximately 95% of the renal parenchyma of the left kidney is effaced by a soft, yellow to tan mass. Similarly, there is a soft, yellow to tan, peripherally expansile, spherical mass obliterating approximately 20% of the renal parenchyma of the right kidney. Three lymph nodes were enlarged in the immediate vicinity of the right kidney and adrenal gland. These lymph nodes ranged in size from 2.5 cm to 3.5 cm in diameter and on cut section, the corticomedullary distinction was completely obscured by firm, tan, soft, tan to white, variably sized (4-7 mm in diameter) coalescing nodules. The brain was grossly unremarkable.

Laboratory results:

No additional testing performed

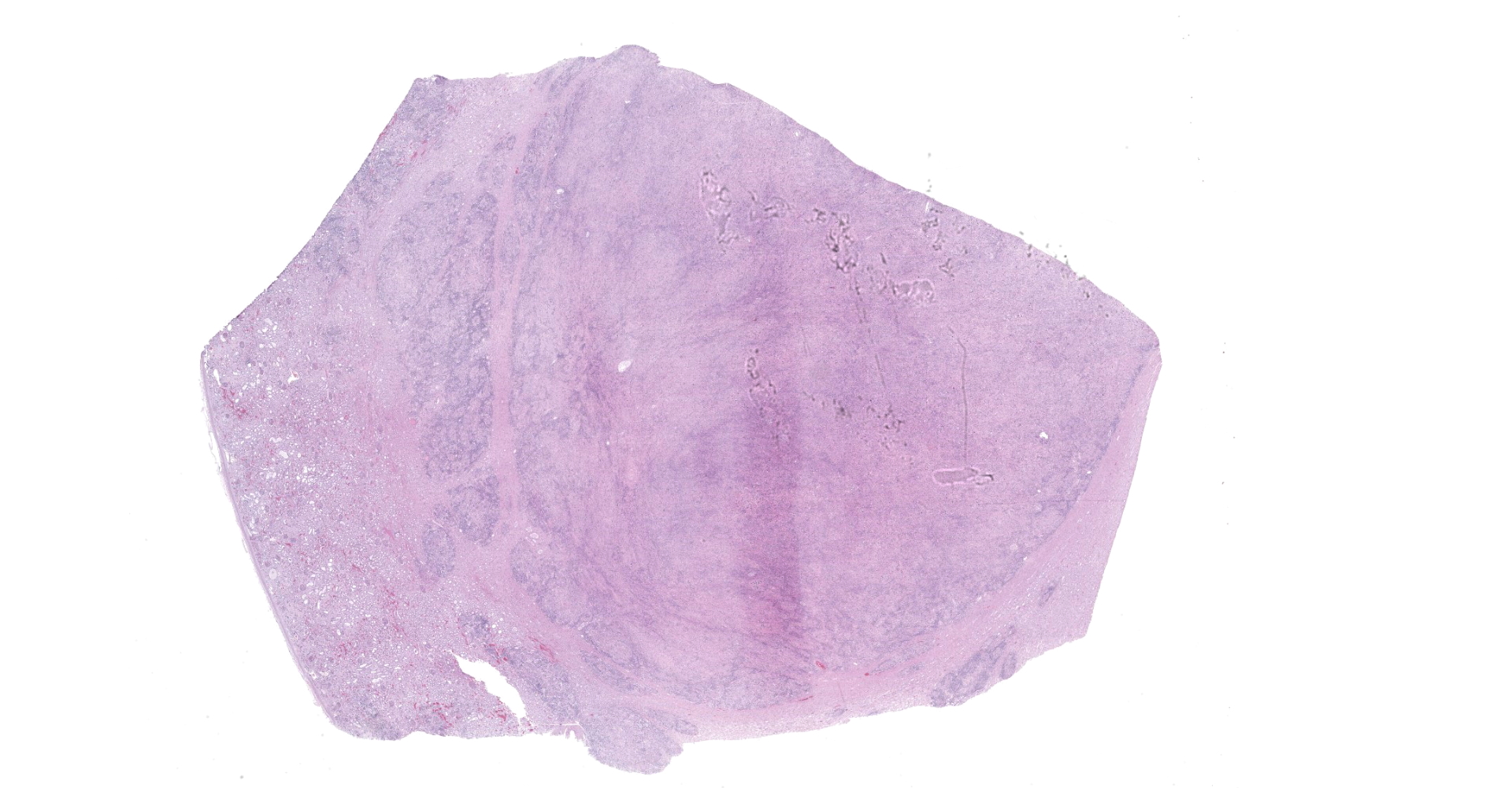

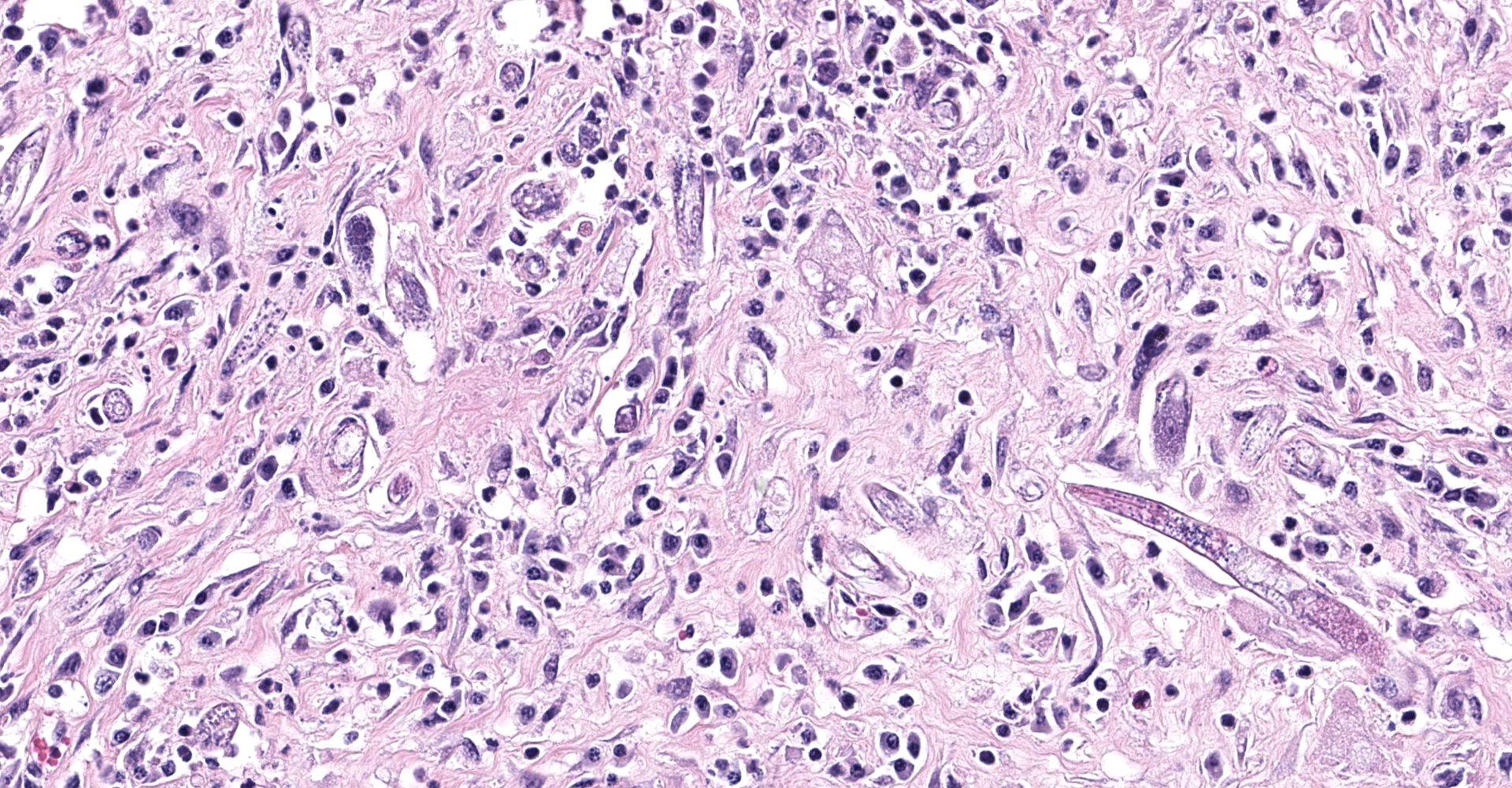

Microscopic description:

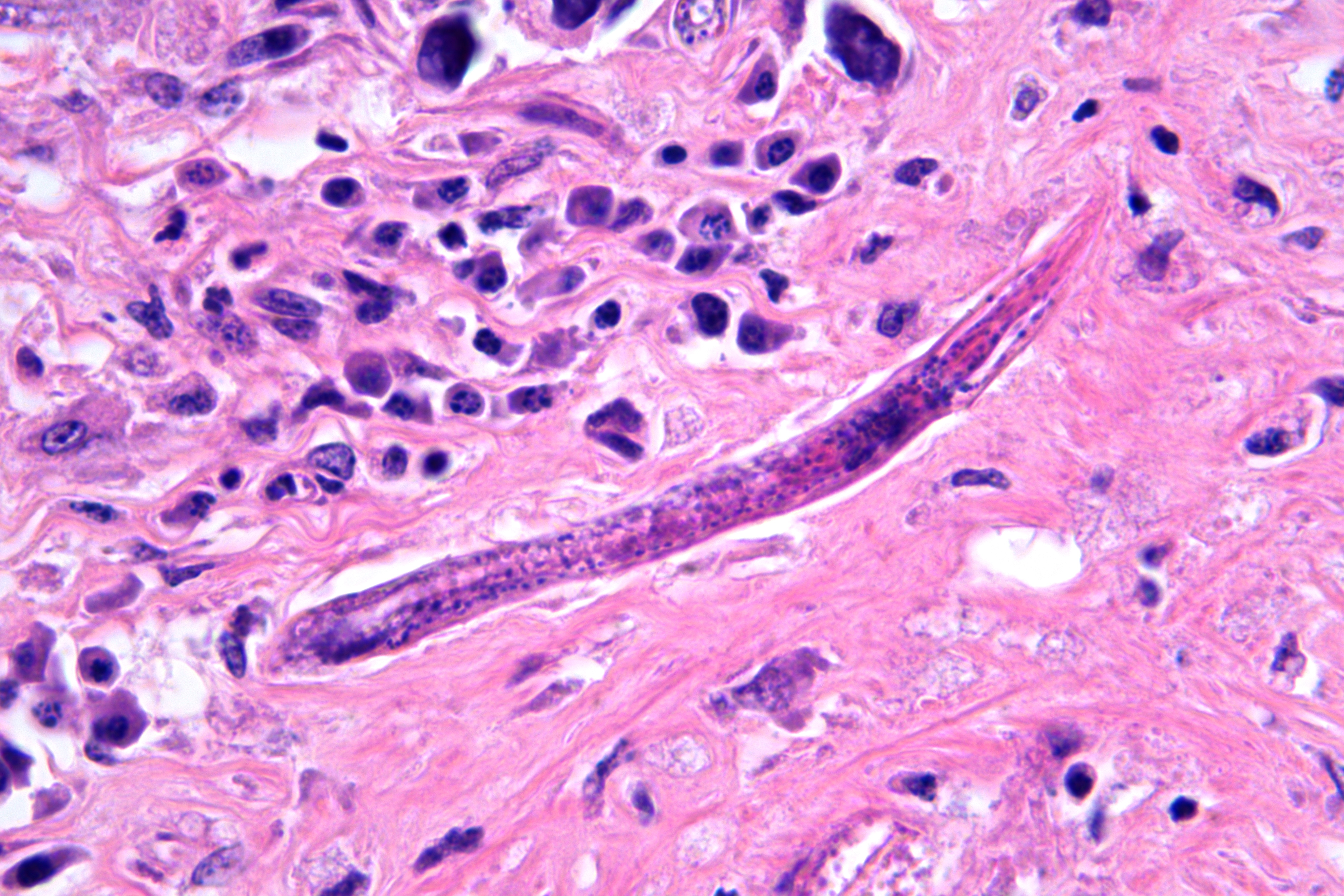

Obliterating approximately 90% of the renal parenchyma within the section are multifocal to coalescing, variably sized, moderately to densely cellular aggregates of inflammatory cells composed predominately of epithelioid macrophages that are often multinucleated (Langhans-type) admixed with moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells and fewer eosinophils separated by abundant, variably mature, fibrous connective tissue. The described inflammatory cells are variably centered on and around large numbers of randomly distributed, tangential and cross-sections of adult and larval nematodes as well as numerous nematode eggs. The adult nematodes are approximately 15-20 microns in diameter and up to 300-400 microns in length, and have a thin cuticle, platymyarian-meromyarian musculature, intestinal tract, and characteristic rhabditiform esophagus with a corpus, isthmus and terminal bulb. A uterus containing a dorsoflexed ovary is also occasionally identified within the adult nematodes. Larval nematodes are also present and typically measure 10-15 microns in diameter and 150-250 microns in length and have the characteristic rhabditiform esophagus. Parasitic eggs are 10 x 25-40 microns, ovoid, and both embryonated and larvated.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Kidney: Nephritis, granulomatous, lymphoplasmacytic, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with myriad intralesional rhabditoid nematode adults, larvae, and eggs, etiology presumptive Halicephalobus gingivalis

Contributor's comment:

In addition to nephritis, microscopic examination of the brain and lymph node from this horse identified both meningoencephalitis and lymphadenitis with intralesional rhabditoid nematodes that were consistent with Halicephalobus gingivalis.

Halicephalobus gingivalis is a facultative, opportunistic nematode of the order Rhabditidia, family Panagrolaimidae. The life cycle and pathogenesis of this opportunistic pathogen is still poorly understood. Halicephalobus nematodes are found free-living in association with water, soil, and decaying organic matter and it is thought that transmission occurs primarily via wounds in the skin or mucous membranes.7,9 Rarely, other routes of infections have been suggested, including transmammary.12 Upon infection, dissemination of the infection is then thought to occur hematogenously.6 Although both males and females exist in the environment, only female nematodes have been observed within microscopic lesions, suggesting that within a host, reproduction occurs asexually via parthenogenesis.7,9

In veterinary species, this parasitic infection is considered uncommon and sporadic, however when described, has been most commonly reported in horses. To date, only a single case series of H. gingivalis infection in cattle has been published.4 Cases in domestic horses have been identified worldwide, including the Southwestern United States, which is where this horse originated (specifically was from New Mexico). The most commonly reported sites of infection in horses are the brain, kidneys, lymph nodes, oral and nasal mucosa, and adrenal glands.3,6,7,11 Very rare cases of meningoencephalitis and myelitis associated with H. gingivalis infection have been described in humans.9-10

Contributing Institution:

Midwestern University College of Veterinary Medicine

Diagnostic Pathology Center

https://www.mwuanimalhealth.com/diagnostic-pathology-center

JPC diagnosis:

Kidney: Nephritis, granulomatous, chronic, focally extensive, severe, with adult and larval rhabditid nematodes and eggs.

JPC comment:

This rhabditoid nematode was previously known as Micronema deletrix, and while primarily affecting equids, it has been described in other species as well. Numerous cases of fatal encephalitides have occurred in humans8 and horses, with several cases observing larva in CSF fluid collected either antemortem or postmortem. The migrating larva induced a sterile neutrophilic and mononuclear pleocytosis.1

These are free living nematodes, that thrive in soil, compost, manure, even deep within the core of the Earth. A facultative parasite, it infects horses more frequently than humans, and even less frequently cattle. In cases where disseminated disease occurs, they may be seen in kidneys, the brain or spinal cord, lymph nodes, oronasal mucosa, adrenal glands, the heart, and even bone (mandibular and maxillary infections reported).

Descriptive features of H. gingivalis include a diameter of approximately 15-25µm, a smooth cuticle, platymarian-meromyarian musculature, a rhabditiform esophagus composed of a corpus, isthmus, and bulb, a gastrointestinal tract lined by uninucleate cuboidal cells, and a single genital tract. Within well-developed lesions, tangential and cross sections of adults as well as larva are easily visualized, with intermixed 10-15µm diameter, ovoid, embryonated eggs.5

From its first description in a nasal swelling of a horse in 1965, it has enjoyed broad spread across the world into diverse environments. Cases of H. gingivalis infection in horses have been reported in the United States, Canada, Brazil, the United Kingdom, France, Austria, and Turkey. The nematode's ability to survive in varied environmental conditions allows infection of horses, and humans in infrequent cases.2

References:

- Adedeji AO, Borjesson DL, Kozikowski-Nicholas TA, Cartoceti AN, Prutton J, Aleman M. What is your diagnosis? Cerebrospinal fluid from a horse. Veterinary Clinical Pathology. 2015;44(1):171-172.

- Bowman DD. Georgis' Parasitology for Veterinarians, 10th Ed. St. Louis, MO:Elsevier. 2014;191-192.

- Bryant UK, et al. Halicephalobus gingivalis-associated meningoencephalitis in a Thoroughbred foal. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2006; 18:612-615.

- Enemark HL et al. An outbreak of bovine meningoencephalomyelitis with identification of Halicephalobus gingivalis. Vet Parasitol. 2016;218-82-86.

- Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. Morphologic characteristics of rhabditoids in tissue section. In: An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Washington DC, AFIP Press, pp. 14-16.

- Henneke C et al. The distribution pattern of Halicephalobus gingivalis in a horse is suggestive of a haemotogenous spread of the nematode. Acta Vet Scand 2014; 56:1-4.

- Hermosilla C et al. Fatal equine meningoencephalitis in the United Kingdom caused by the panagrolamid nematode Halicephalobus gingivalis: case report and review of the literature. Eq Vet J. 2011; 43: 759-763.

- Lim CK, Crawford A, Moore CV, et al. First human case of fatal Halicephalobus gingivalis meningoencephalitis in Australia. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2015;53:1768-1774.

- Onyiche TE et al. Parasitic and zoonotic meningoencephalitis in humans and equids: Current knowledge and the role of Halicephalobus gingivalis. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2018; 3(1): 36-42.

- Papadi B et al. Halicephalobus gingivalis: A rare cause of meningoencephalomyelitis in humans. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013; 88(6): 1062-4.

- Wilkins PA, et al. Evidence of Halicephalobus delatrix (H. gingivalis) from dam to foal. J Vet Intern Med. 2001;15:412-417.