Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 3

September 6th, 2017

CASE III: E 1246-14 (JPC 4102122).

Signalment: 24-year-old, intact female, polo pony (Equus ferus caballus).

History: Only little clinical history was provided. Recurring polypoid structures had been observed in the left nostril for seven years, especially growing during the spring and summer period. The polypoid structures had formerly been diagnosed as rhinosporidiosis seven years ago.

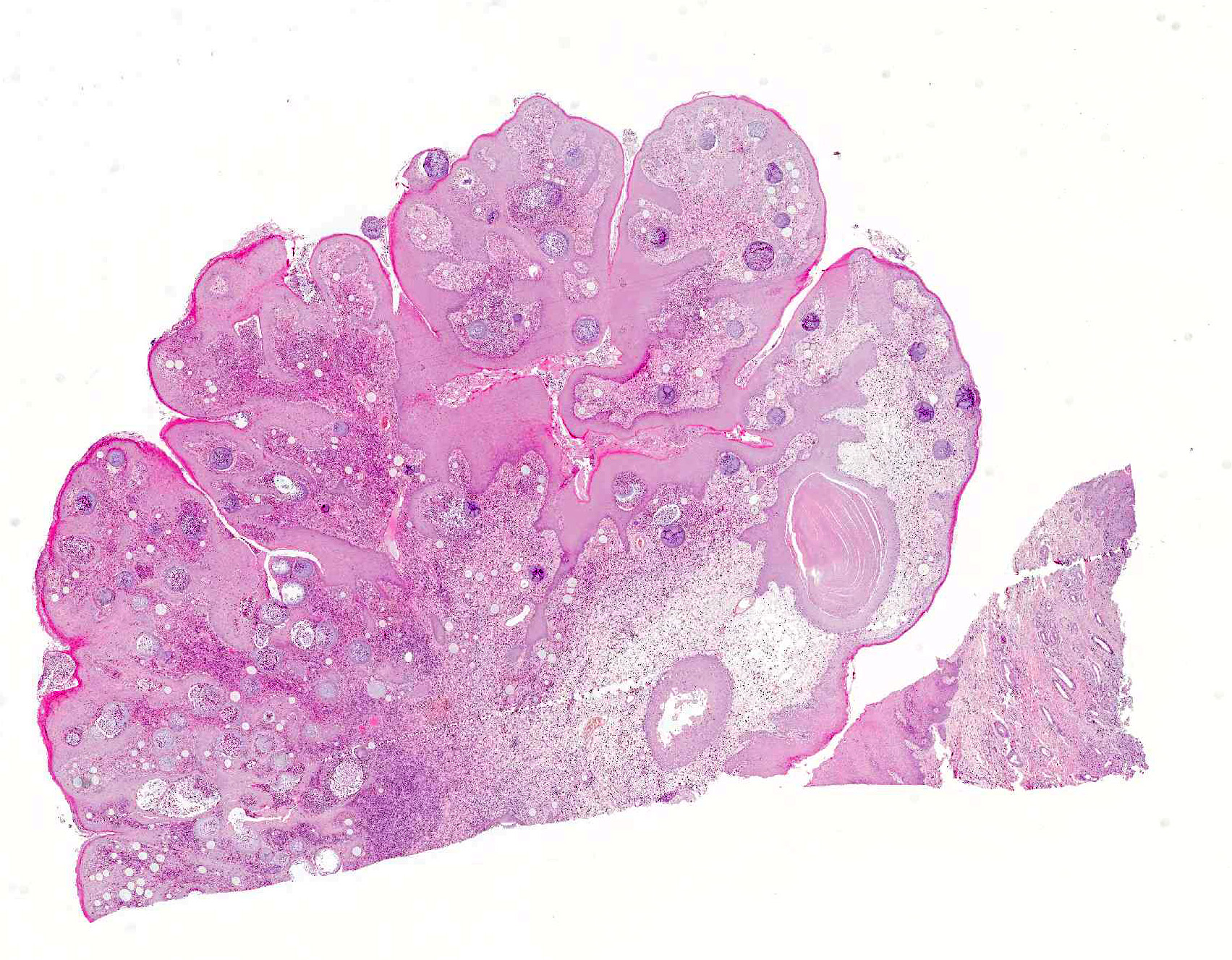

Gross Pathology: A tissue sample from the nasal mucosa fixed in formalin was submitted measuring 2.8 x 1.9 x 1.4 cm, containing two separate masses connected by a tissue bridge. The first mass measured 2.3 x 1.4 x 1.1 cm and the second mass was 1.9 x 1.9 x 1.2 cm in size. Both masses were partially ulcerated.

Laboratory results: None provided.

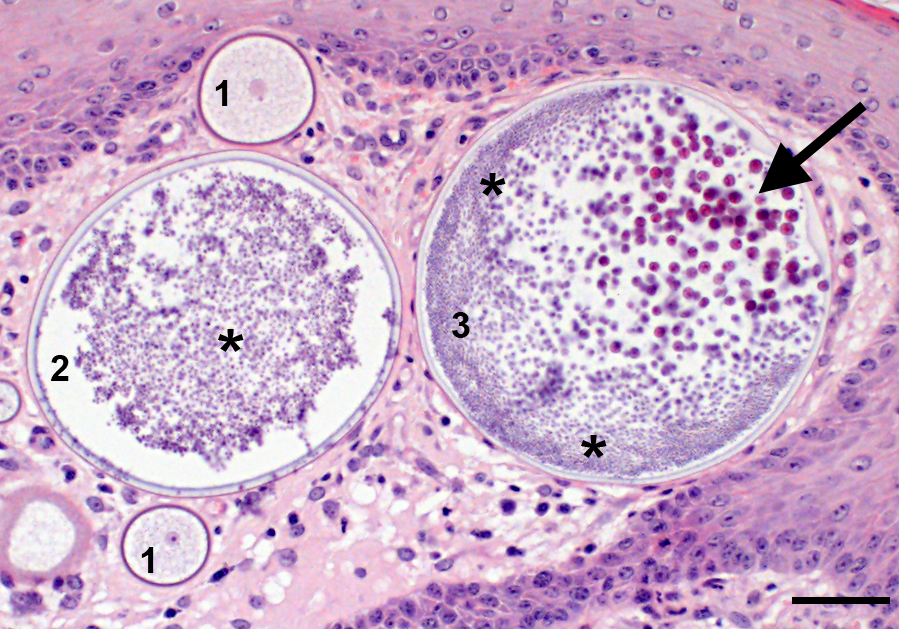

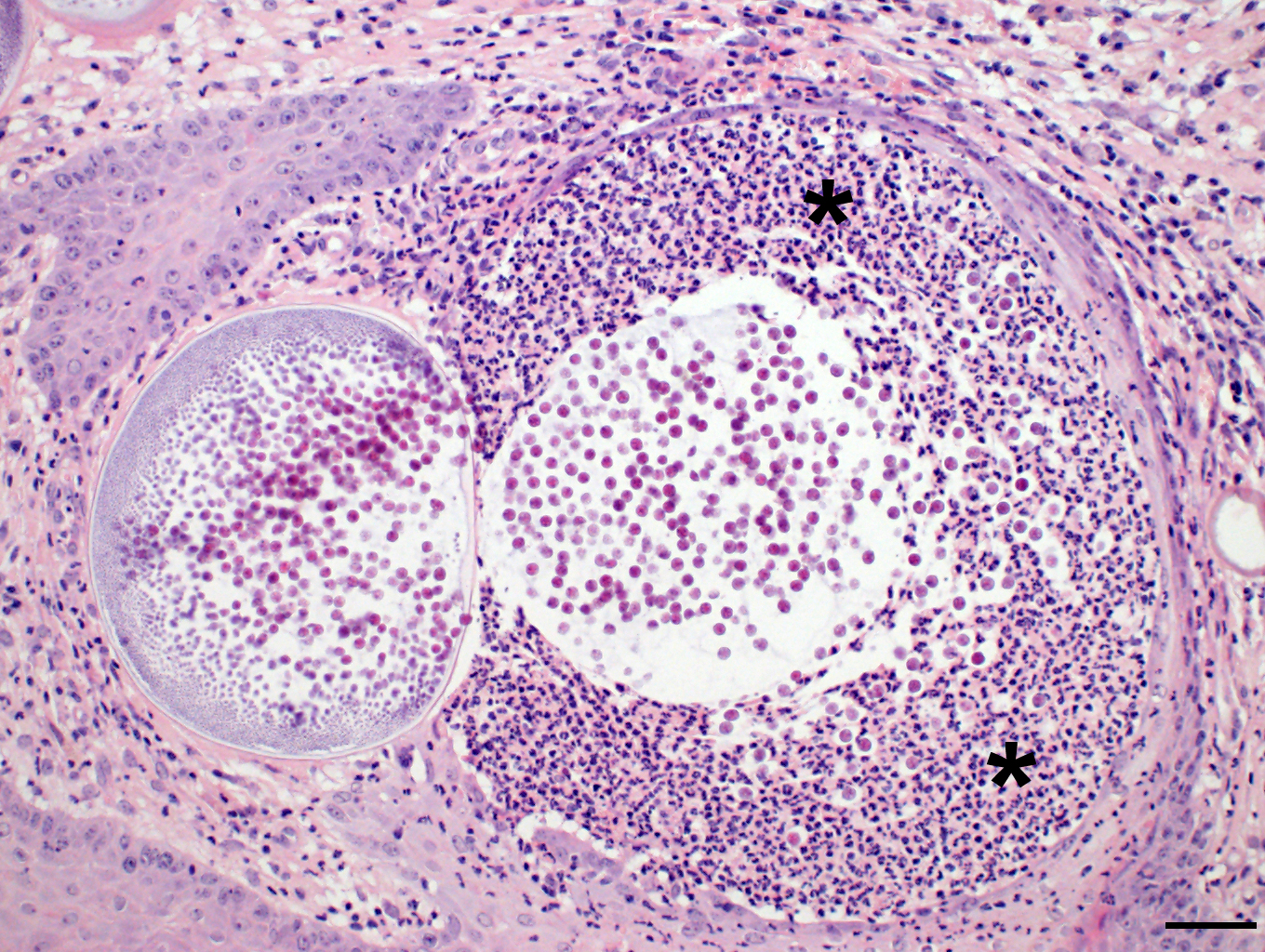

Microscopic Description: Nasal mucosa: There is a polypoid, multilobulated mass expanding the submucosa, formed by loosely fibrovascular tissue and covered by hyperplastic stratified squamous epithelium. Within the fibrovascular tissue, there is marked infiltration with lymphocytes, moderate numbers of viable and degenerated neutrophils and macrophages and fewer plasma cells. Randomly distributed throughout the mass are immature to mature, partially ruptured fungal sporangia ranging from 10 to 300 µm in diameter. The smaller round immature sporangia measure 10 to 60 µm in diameter, have a central nucleus and a prominent nucleolus surrounded by loose, basophilic granular material. Their unilamellar wall is up to 2 µm thick. The intermediate sporangia measuring 60 to 200 µm in diameter show a bilamellar wall and an accumulation of ovoid, immature endospores of up to 1 µm in diameter. Large mature sporangia also have a hyaline, bilamellar wall and the immature endospores are located closer to the sporangial wall whereas the 12 µm large, eosinophilic, globular mature endospores are located more centrally. Few of the sporangia are ruptured, showing a discharge of endospores into the surrounding tissue and a marked infiltration by neutrophils. The overlying hyperplastic epithelium shows multifocal keratinization and multifocal erosions with formation of serocellular crusts.

Adjacent to the mass the mucosa is lined by multifocally pseudostratified columnar epithelium and prominent seromucous glands.

Contributors Morphologic Diagnosis: Nasal mucosa: Rhinitis, proliferative, lymphoplasmacytic and pyogranulomatous, chronic-active, focally-expansive, severe with epithelial hyperplasia and fungal sporangia consistent with Rhinosporidium seeberi.

Contributors Comment: Rhinosporidum seeberi is a fungal-like organism causing the mucocutaneous disease rhinosporidiosis in humans and many different animal species, including mammalsand birds.3 Previously classified as a fungus, currently the agent is assigned to a new class of parasites the DRIP clade respectively the clade of the Mesomycetozoea.6 Rhinosporidiosis is endemic in different countries in Asia and Africa with high incidence in India, Sri Lanka and Argentina; however, the disease has been reported in about 70 different countries worldwide. The natural habitat of R. seeberi is most likely the ground water. Infection occurs primarily via the nasal cavity through penetration of infectious spores via superficial trauma in the epithelium. The disease seems to be infective but not infectious, although the life cycle and pathogenesis are not yet fully understood. In vitro cultivation is very challenging; so far, the agents isolation from its habitat was not successful. 1

The typical clinical appearance of nasal or laryngeal rhinosporidiosis is single to multiple, granular, pink to red, pedunculated or sessile, polypoid growths (strawberry-like appearance).1,6 The masses are non-infiltrating, slow-growing and painless.5 Burgess et al.2 hypothesized that the organism has the ability to persist subclinically for long a time.

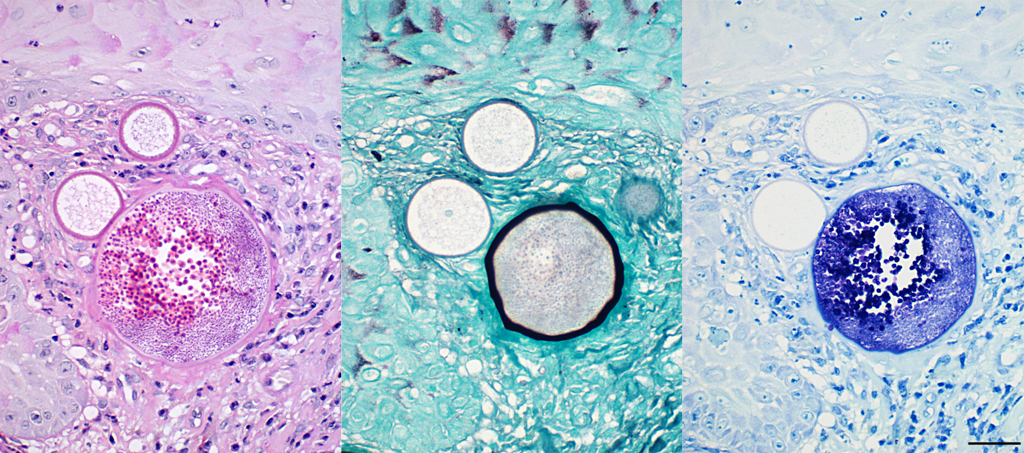

The histopathological appearance of rhinosporidiosis seems to be the same in animals as in humans. Histological differentials include Coccidioides immitis and Emmonsia parvum because of the size of the sporangia3; nevertheless, the identification of all different stages allows a reliable, histopathological diagnosis.1 A periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reaction clarifies the thick, unilamellar, eosinophilic and PAS-positive wall of immature sporangia whereas the bilamellar wall of intermediate sporangia stains partially positive for PAS, the inner layer shows positive staining for Gomori methenamine silver.2 Endospores additionally stain positive with toluidine blue.

The treatment of choice is the complete surgical excision of the polypoid masses using electro-cautery. Recurrence is common, in which sessile polyps seem to recur more often than pedunculated polyps. Interestingly, rare cases of spontaneous regression have been reported.1

Rhinosporidiosis in animals and humans is an extremely rare disease in Europe6; the observed infections are mostly linked to former stays in endemic countries.4 Due to globalization and the growth of international trade with animals, Rhinosporidiosis could become an emerging disease in European countries.

JPC Diagnosis: Nasal mucosa: Rhinitis, proliferative, chronic, diffuse, moderate with numerous sporangia and endospores, polo pony, equine.

Conference Comment: This case demonstrates a classic example of nasal rhinosporidiosis in a horse. Participants described nodular lesions with overlying hyperplastic mucosa that contains variably sized sporangia and endospores in different stages of maturation surrounded by inflammation and fibrous connective tissue. The conference moderator and attendees discussed the staining patterns of sporangia and endospores. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) highlights endospores, unilamellar walls of juvenile sporangia, and outer walls of mature sporangia and Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) indicates the inner wall of mature sporangia. 2, 4

Rhinosporidium seeberi exists in three forms in infective tissue. It develops as spherical sporangia (6-300 µm) which mature to develop a thick bilamellar wall. The nuclei undergo changes as well, maturing from uninucleate immature sporangia, undergoing nuclear division, and forming numerous uninucleate endospores (6-7 µm) characteristic of mature sporangia. Once the sporangium matures, the endospores are released through a break in the cell wall. Free spores consequently enlarge to form sporangia and continue the cycle in tissue. Grossly, rhinosporidiosis has a nodular, polypoid appearance with numerous pinpoint white foci on the surface representing larger spherules filled with sporangiospores. Systemic dissemination is rare and the disease is seldom fatal, but can cause complications due to obstruction of airways or bleeding. Sporangia generally incite a chronic granulomatous response, whereas free endospores incite an acute neutrophilic response. Eosinophils are rare. Multinucleated giant cells are often prominent around and within empty mature sporangia having entered through the break in the cyst wall. 3, 4, 8

There are very few differentials for Rhinosporidium seeberi due to their large size; they are the largest endosporulators, and characteristic location in the upper respiratory tract. Sporangia of Coccidiodes immitis, for example, are rarely larger than 80-200 µm. In addition, their endospores lack internal globular bodies and only their walls stain with fungal stains. Empty sporangia may resemble Blastomyces dermatitidis; however, there is no broad-based budding present, and the presence of mature sporangia with endospores is not characteristic of simple yeast. Another differential is Emmonsia parvum which has much thicker trilaminar adiaspore walls.4

Finally, a rarely seen condition that may be confused with Rhinosporidium seeberi is myospherulosis. Myospherulosis is a type of foreign-body reaction in which erythrocytes interact with an exogenous substance, usually ointments, or endogenous fat and form subcutaneous nodules composed of macrophages that have intracytoplasmic homogenous eosinophilic spherules. These structures stain negatively with PAS, but the intracytoplasmic spherules are positive for endogenous peroxidase identifying them as phagocytized erythrocytes.4, 9

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Freie Universität Berlin

http://www.vetmed.fu-berlin.de/en/einrichtungen/institute/we12/index.html

References:

- Arseculeratne SN. Recent advances in rhinosporidiosis and Rhinosporidium seeberi. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2002;20:119-131.

- Burgess HJ, Lockerbie BP, Czerwinski S, Scott M. Equine laryngeal rhinosporidiosis in western Canada. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;24(4):777-780.

- Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:476, 579.

- Chandler FW, Kaplan W, Ajello L. Histopathology of Mycotic Diseases. Chicago, IL: Year Book Medical Publishers, Inc.; 1980:109-111.

- Kennedy FA, Buggage RR, Ajello L. Rhinosporidiosis: a description of an unprecedented outbreak in captive swans (Cygnus spp.) and a proposal for revision of the ontogenic nomenclature of Rhinosporidium seeberi. J Med Vet Mycol. 1995;33:157-165.

- Leeming G, Hetzel U, Campbell T, Kipar A. Equine rhinosporidiosis: an exotic disease in the UK. Vet Rec. 2007;160:552-554.

- Leeming G, Smith KC, Bestbier ME, Barrelet A, Kipar A. Equine rhinosporidiosis in United Kingdom. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1377-1379.

- Lopez A, Martinson SA. Respiratory system, mediastinum, and pleurae. In: Zachary JF ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 490.

- Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:560.

- Nollet H, Vercauteren G, Martens A, Vanschandevijl K, Schauvliege S, Gasthuys F, Ducatelle R, Deprez P. Laryngeal rhinosporidiosis in a Belgian warmblood horse. Zoonoses Public Health. 2008;55:274-278.