Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 24

May 2nd, 2018

CASE IV: N17-104-1 (JPC 4101578)

Signalment: 22-year-old, female, intact, red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), reptile.

History: This turtle presented for persistent abnormal egg laying behavior, and had been treated for dystocia with 8 retained eggs several months prior at the referring veterinarian. No remaining eggs were observed on radiographs at presentation, and bloodwork revealed elevated liver enzymes (AST), azotemia, hyperkalemia, and hypoproteinemia. Coeloscopic ovariohysterectomy was performed and revealed multiple enlarged ovarian follicles with numerous adhesions to the body wall and numerous yolk droplets on serosal surfaces. Due to the inability to completely surgically resect all ovarian tissue and poor prognosis for recurrent coelomitis, euthanasia was elected.

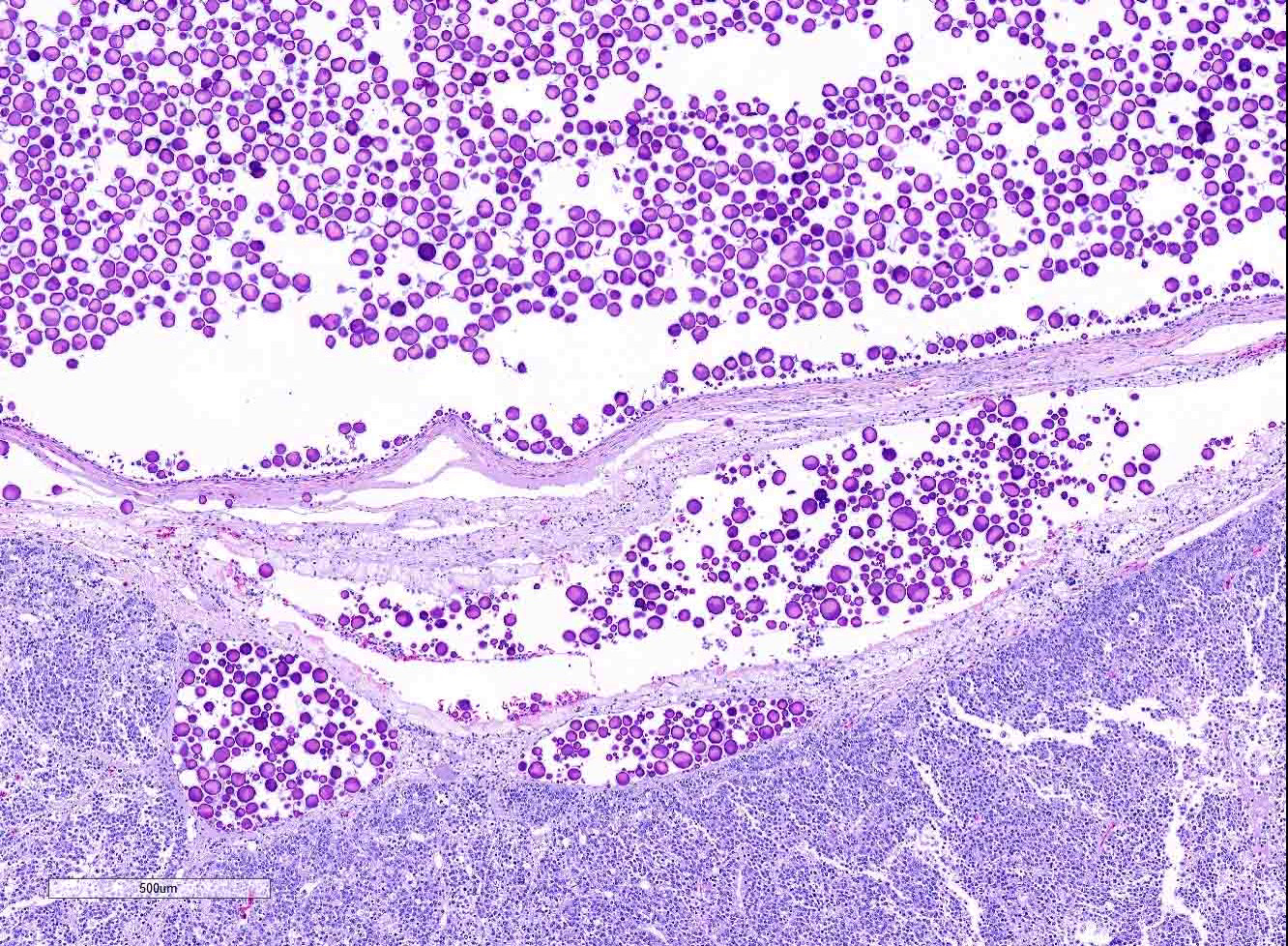

Gross Pathology: Within the caudal coelom, there is a mixture of healthy mature and immature follicles, bilaterally, with an 11 x 6 cm, yellow to tan, soft, friable, fatty, ovoid mass associated with the right-sided ovarian tissue and 2-3 mature follicles embedded within the capsule. On the surface of the opposing coelomic wall are patchy, thin, yellow, fibrinous adhesions. On cut section, the center of the mass is markedly friable and greasy, and homogenously pale tan. Sections of the mass did not float when placed into formalin.

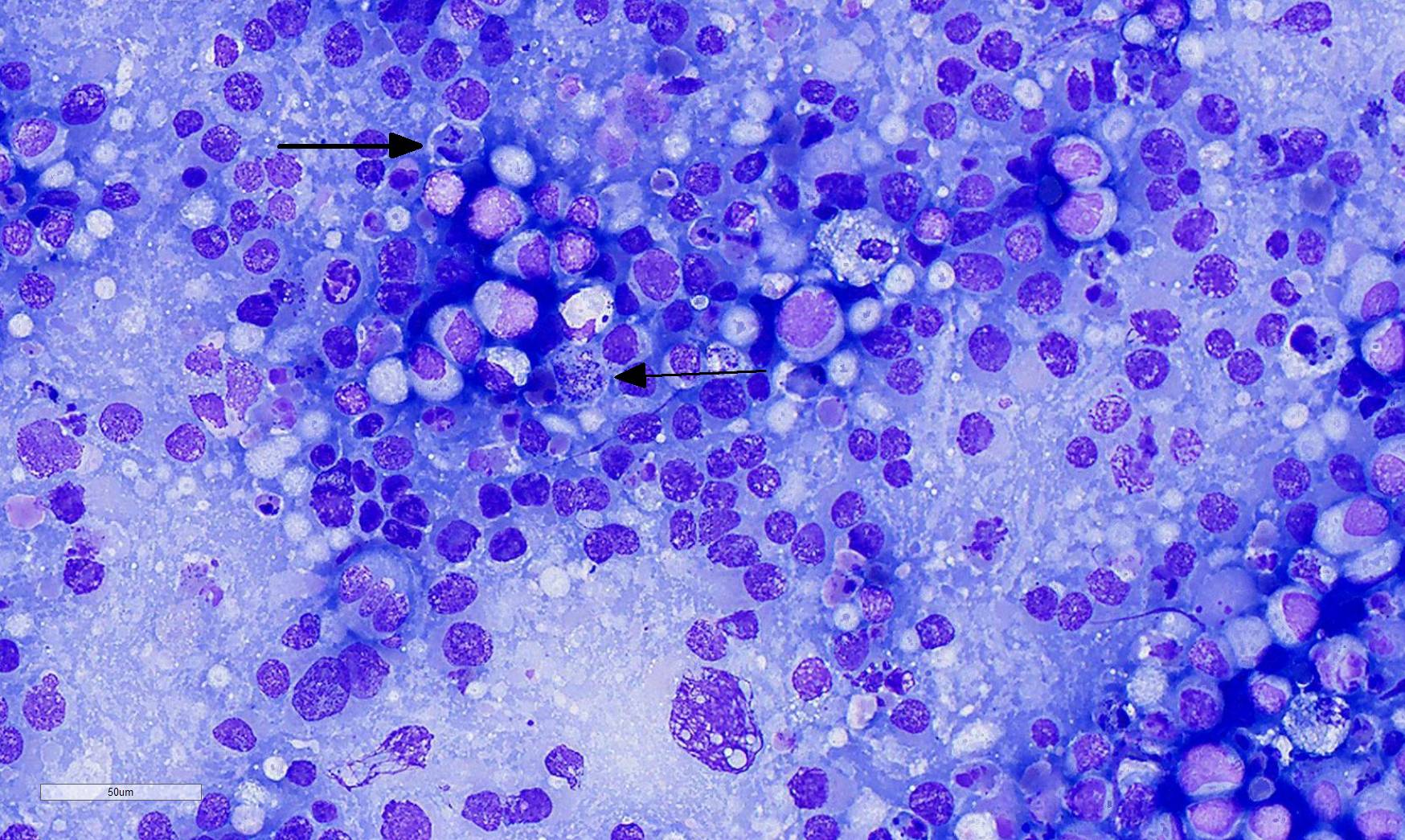

Laboratory Results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.): Cytologic impressions of the mass revealed small clusters of markedly pleomorphic, large, round to polygonal cells arranged singly or in loose aggregates on a moderately proteinacous background with scattered red blood cells. Cells range from 20 to 50 um in diameter, with distinct cell borders and contain moderate, pale basophilic, occasionally vacuolated cytoplasm. Nuclei are large and round to oval with reticular chromatin and contain multiple prominent nucleoli. Binucleation and multinucleation is frequent. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are marked, and mitotic activity is moderate.

Microscopic Description:

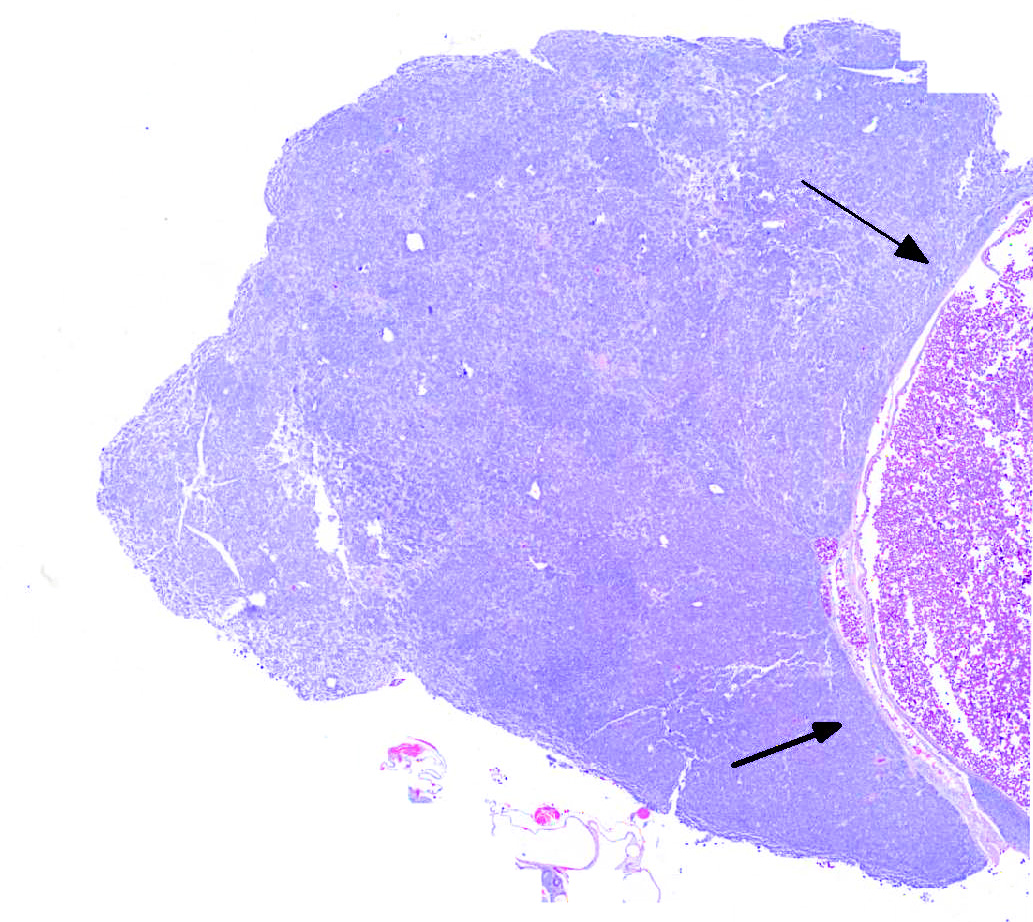

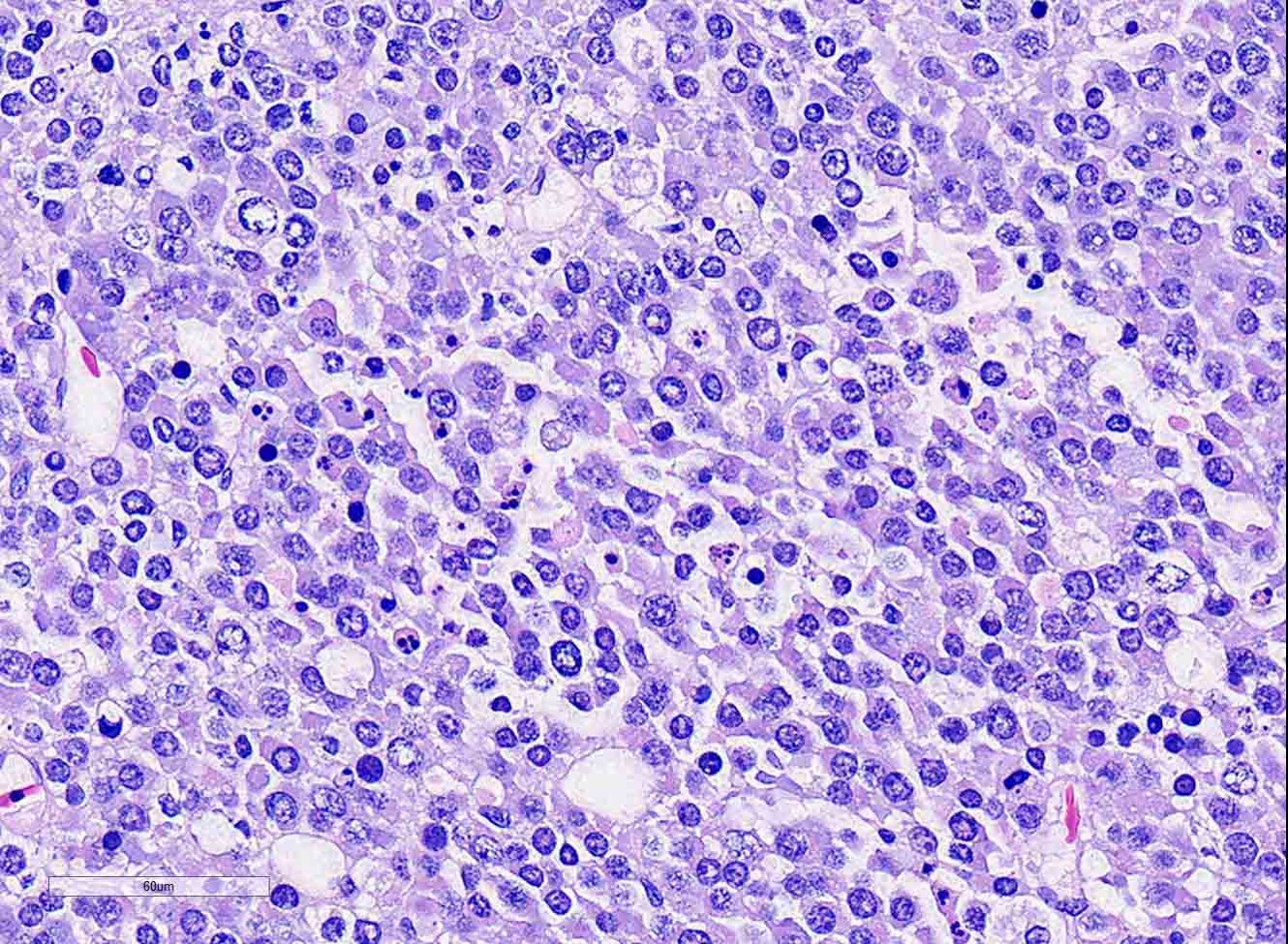

Ovary: Displacing previtellogenic and vitellogenic ovarian follicles, is an unencapsulated, poorly demarcated, expansile neoplasm composed of sheets of round to polygonal cells, occasionally forming indistinct lobules, separated by very thin collagenous stroma. Neoplastic cells have distinct cell borders and moderate amounts of homogenous, pale eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei are round to oval, centrally located with vesiculate chromatin pattern and contain 1 to 3, prominent nucleoli. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are moderate. There are 19 mitotic figures in 10 hpf. There is frequent multifocal individual cell necrosis and low numbers of scattered lymphocytes.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Ovary, dysgerminoma

Contributor’s Comment: Dysgerminomas are germ cell tumors that arise from undifferentiated, pluripotent germ cells in the ovary.6,12,14,15 Other germ cell tumors, such as teratoma and embryonal carcinoma, are distinguished by somatic differentiation and maturation of neoplastic cells towards an embryonic tissue type(s). In chelonians, germ cell tumors are extremely rare.3,5,6,9,12 Dysgerminomas have been reported in 2 red-eared sliders and a snapping turtle. Teratomas were reported in a red-eared slider and a snapping turtle. In other veterinary species, dysgerminomas are similarly rare, and have been reported in dogs, cats, horses, maned wolves, Eastern rosella, and mountain chicken frogs.2,10,15 Maned wolves in captivity have been reported to have an increased prevalence of ovarian tumors, with suspected hereditary predisposition for dysgerminomas.10 In humans, dysgerminomas can occasionally be hormonally functional and human chorionic gonadotropin, produced by syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells, can contribute to aberrant follicular maturation and ovulation and pregnancy-like signs.11,15 Similar hormonal influence by the tumor contributing to the clinical signs of chronic egg laying behavior in this turtle is speculative. Although dysgerminomas are considered malignant, metastasis is rarely observed.

Clinical signs across all species is largely non-specific, and related to the effects of a space-occupying mass within the abdomen. Turtles have shown signs of anorexia, lethargy, carapace dysecdysis, or inability to swim normally, and, in this case, abnormal egg laying behavior.3,5,9 Grossly, in chelonians, dysgerminomas appear as unilateral, intracoelomic, white to yellow, friable, fat-like masses, ranging from 4 to 11 cm, and are associated with ovarian tissue. Microscopic examination reveals sheets of round to polygonal cells with large, round to oval vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli, and moderate pale eosinophilic cytoplasm. Mitoses are frequent. Scattered lymphocytes and multifocal regions of ischemic necrosis are occasionally noted.

Immunohistochemistry for germ cell tumors have not been established in chelonians, and was not performed in this case. Currently, a diagnosis of dysgerminoma in people is reliant on positive immunoreactivity with placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) and vimentin.8,11 Recent development of germ cell-selective immunohistochemical markers, OCT3/4 and SALL4, are now also recommended for diagnosis. OCT3/4 is a nuclear transcription factor that plays a role in maintaining pluripotency in primordial germ and stem cells. SALL4 is a nuclear factor with which OCT3/4 interacts, and is involved in totipotency. Both OCT3/4 and SALL4 are strongly expressed in dysgerminomas, but, since they are both markers of pluripotency, they are also expressed in embryonal carcinomas and less differentiated teratomas. CD117 (c-kit) is a proto-oncogene expressed in dysgerminomas, and not in other germ cell tumors. However, only 30% of dysgerminomas demonstrate immunoreactivity. Dysgerminomas are immunonegative for a-fetoprotein, inhibin-a, and S-100.

Immunohistochemical markers for dysgerminomas in veterinary literature are variable across species and, in some cases, show similarities to the immunophenotype observed in people.2,4,15 OCT4 was expressed in dysgerminomas in mountain chicken frogs, but the tumors were immunonegative for vimentin, PLAP, and calretin.2 In the dog, dysgerminomas do not express c-kit, but are immunopositive for SALL4 with variable expression of PLAP and vimentin. Immunohistochemistry with a-fetoprotein, inhibin-a, and S-100 are negative in dogs.4

Based on the gross and microscopic appearance in this case, diagnosis of dysgerminoma is strongly supported. Dysgerminomas should be considered as a differential diagnosis in turtles with a coelomic mass and antemortem identification with cytology may be helpful. As more cases are identified, immunophenotyping for germ cell tumors in turtles can be further elucidated. This is the first report of a red-eared slider with a dysgerminoma showing clinical signs of chronic reproductive behavior, suggesting the possibility of hormonal production by this tumor in this species.

JPC Diagnosis: 1. Ovary: Dysgerminoma, red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), reptile.

- Cytologic impression: Round cell proliferation with intracytoplasmic, eosinophilic granules and foamy macrophages.

Conference Comment: Two types of germ cell tumors have been reported in female domestic animals: dysgerminomas and teratomas. Germ cells arise in the yolk sac, migrating to the gonadal ridge during differentiation, and associate with sex cords before formation of primary follicles.1

Dysgerminoma, a rare ovarian tumor, is most common in the bitch and queen, but have also been identified in the cow, mare, sow, and maned wolves. Dysgerminomas in fish may contain testicular elements. They correspond to seminomas in the testicle and occasionally are hormonally active, resulting in clinical signs of hyperestrogenism. Grossly, dysgerminomas are large, firm, white or gray homogenous tumors that elevate the ovarian capsule and can contain areas of hemorrhage, necrosis or cystic cavitations. Microscopically, they are densely cellular and composed of primitive germ cells arranged in sheets, cords, and nests separated by a thin connective tissue septa. Neoplastic cells have large vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli and scant eosinophilic cytoplasm giving them a blastic appearance. Multinucleated cells and bizarre mitotic figures are common as is metastasis to regional lymph nodes or explantation to adjacent tissues.

Teratomas are less common and are composed of at least two of the germinal layers (endoderm, mesoderm, or ectoderm).

A recent article7 (discussed during the conference) identified a presumptive ovarian dysgerminoma in an orange-spot freshwater stingray which was composed of sheets of round cells arranged in solid and cystic areas with a scant cytoplasm, moderate anisokaryosis, multiple nucleoli and frequent mitotic figures. Additionally, the moderator shared an interesting case in a medaka in which there was spermatogenic progression within the dysgerminoma. Differentials discussed by conference participants included lymphoma, histiocytic tumor, and sex cord stromal tumor.

Contributing Institution:

Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University

http://vet.tufts.edu/foster-hospital-small-animals/departments-and-services/pathology-service/

References:

- Agnew DW, MacLachlan NJ. Tumors of the genital systems. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 5th Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2017:690-698.

- Fitzgerald SD, Duncan AE, Tabaka C, Garner MM, Dieter A, Kiupel M. Ovarian dysgerminomas in two mountain chicken frogs (Leptodactylus fallax). J Zoo Wildlife Med. 2007; 38(1): 150-153.

- Frye FL, Eichelberger SA, Harshbarger JC, Cuzzocrea AD. Dysgerminomas in two red-eared slider turtles (Trachemys scripta elegans) from the same household. J Zoo Anim Med. 1988; 19(3): 149-151.

- Hara S, Morita R, Shiraki A, et al. Expression of protein gene product 9.5 and Sal-like protein 4 in canine seminomas. J Comp Path. 2014; 151: 10-18.

- Hidalgo-Vila J, Martinez-Silvestre A, Diaz-Paniagua C. Benign ovarian teratoma in a red-eared slider turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans). Vet Rec. 2006; 159: 122-123.

- Innis CJ, Boyer TH. Chelonian reproductive disorders. Vet Clin Exot Anim. 2002; 5: 555-578.

- Jafarey YS, Berlinski RA, Hanley CS, Garner MM, Kiupel M. Presumptive dysgerminoma in an orange-spot freshwater stingray (Potamotrygon motoro). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 2015; 46(2):382-385.

- Kaspar HG, Crum CP. The utility of immunohistochemistry in the differential diagnosis of gynecologic disorders. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015; 139: 41-54.

- Machotka SV, Wisser J, Ippen R, Nawab E. Report of dysgerminoma in the ovaries of a snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) with discussion of ovarian neoplasms reported in reptilians and women. In Vivo, 1992 Jul-Aug; 6(4): 349-54.

- Munson L, Montali RJ. High prevalence of ovarian tumors in maned wolves (Chrysocyon brachyurus) at the National Zoological Park. J Zoo Wildlife Med. 1991; 22(1): 125-129.

- Nogales FF, Dulcey I, Preda O. Germ cell tumors of the ovary. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014; 138: 351-362.

- Perry SM, Mitchell MA. Reproductive medicine in freshwater turtles and land tortoises. Vet Clin Exot Anim. 2017; 20: 371-389.

- Sever M, Jones TD, Roth LM, Karim FWA, et al. Expression of CD117 (c-kit) receptor in dysgerminoma of the ovary: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Mod Path. 2005; 18: 1411-1416.

- Solano-Gallego L. Reproductive system. In: Raskin RE, Meyer DJ. Canine and Feline Cytology: A Color Atlas and Interpretation Guide. 2nd St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2010: 282-286.

- Strunk A, Imai DM, Osofsky A, Tell LA. Dysgerminoma in an Eastern Rosella (Platycercus eximius eximius). Avian Diseases. 2011; 55: 133-138.