Signalment:

Gross Description:

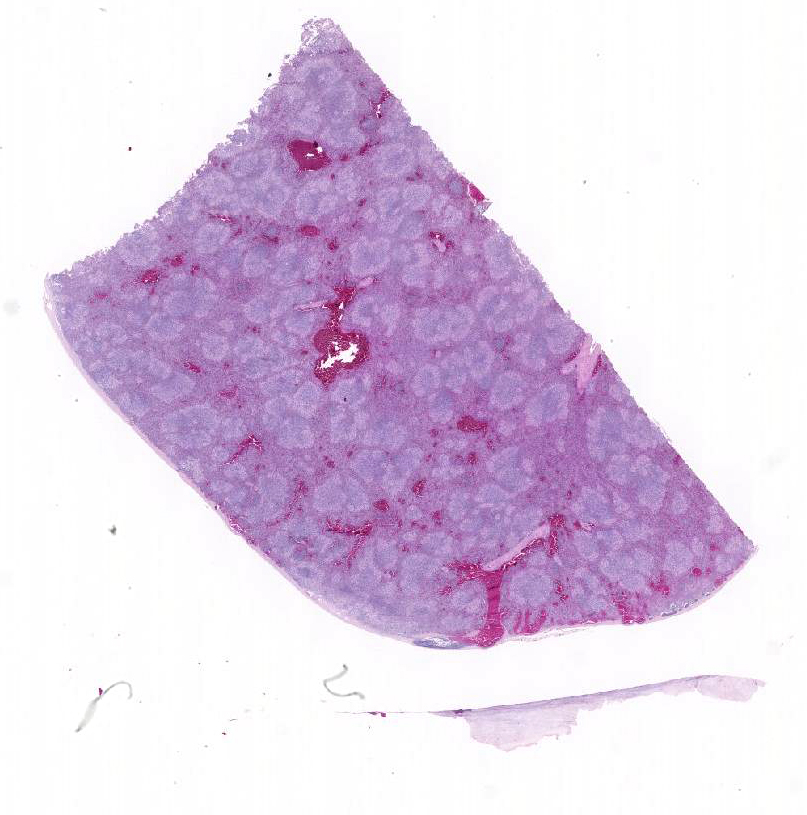

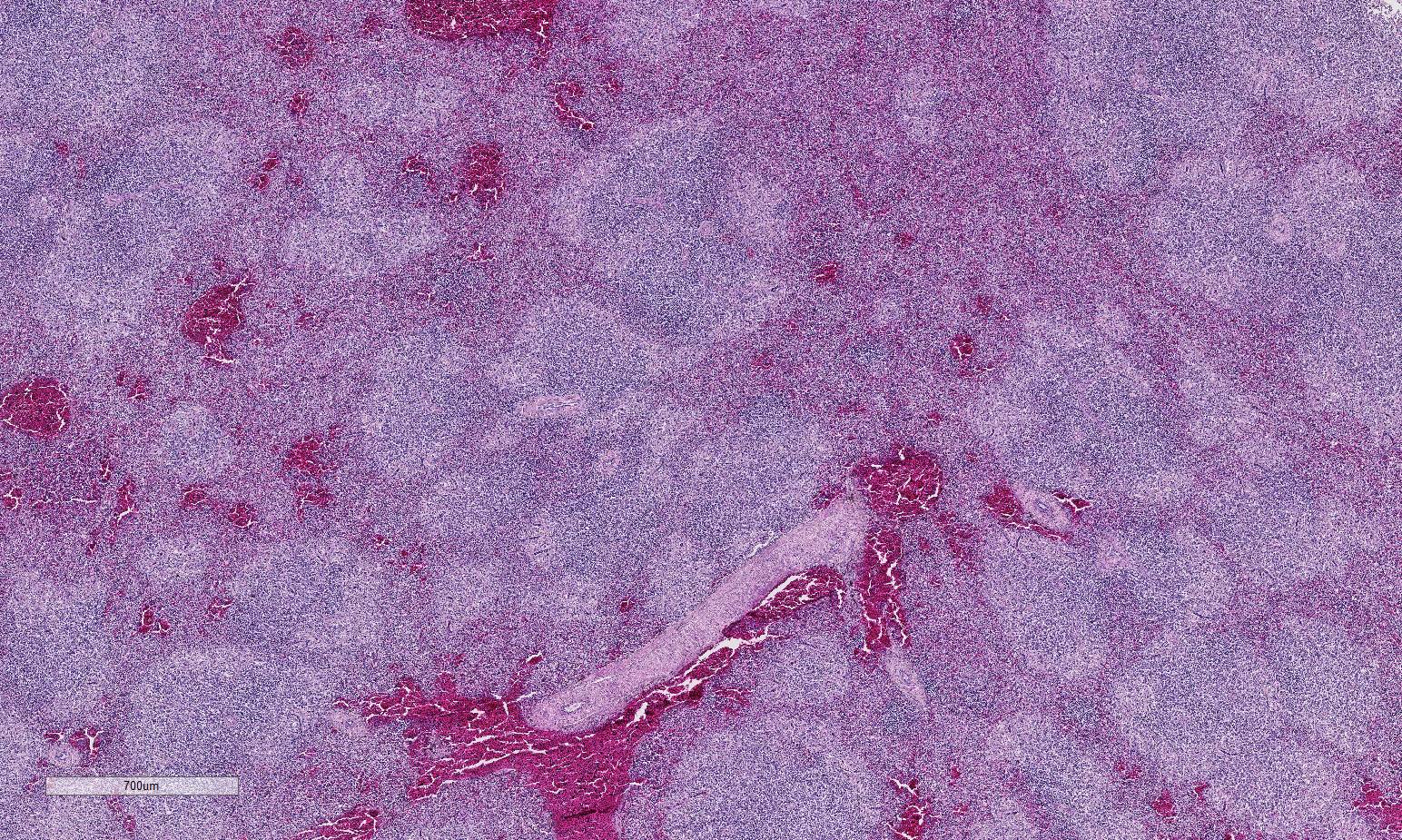

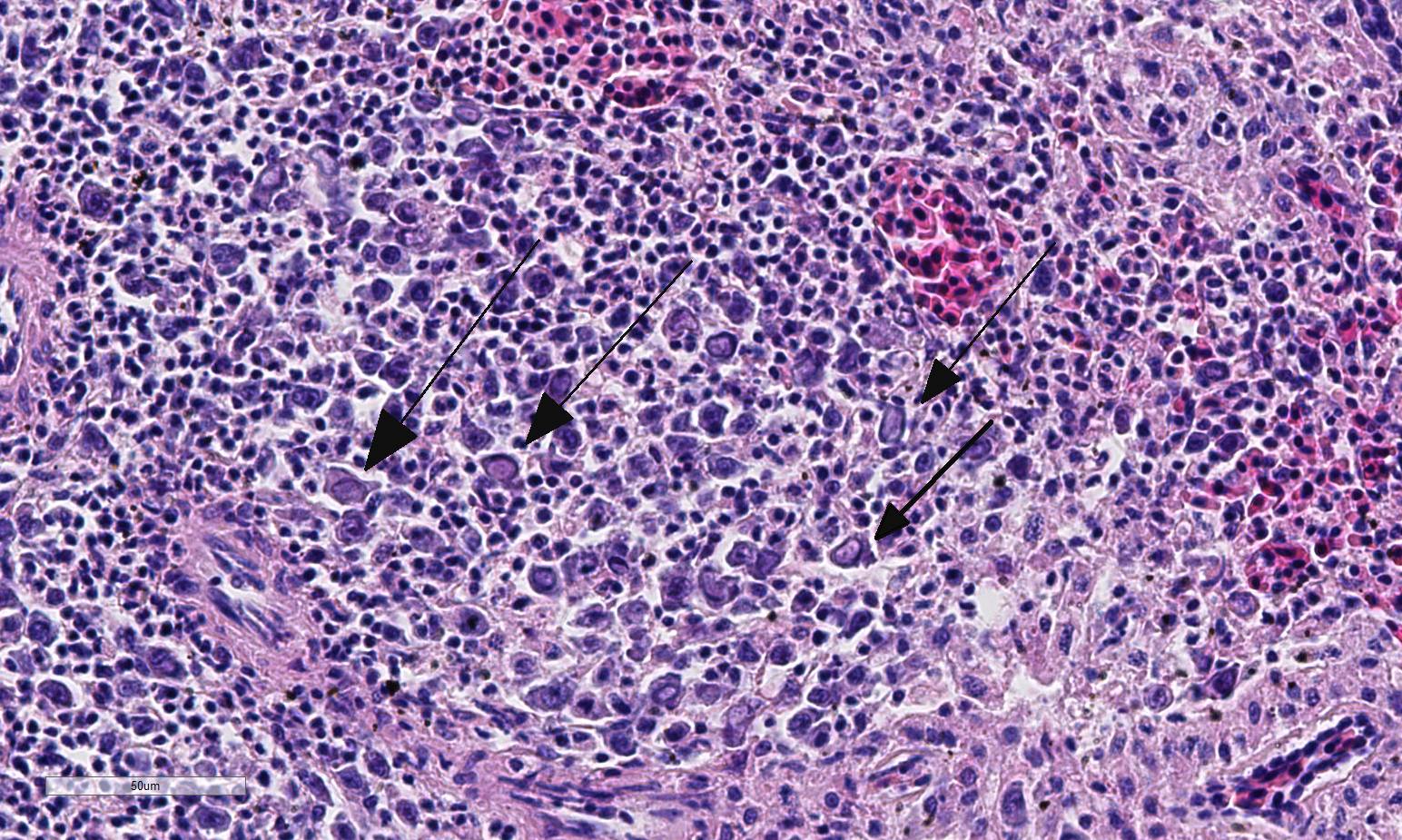

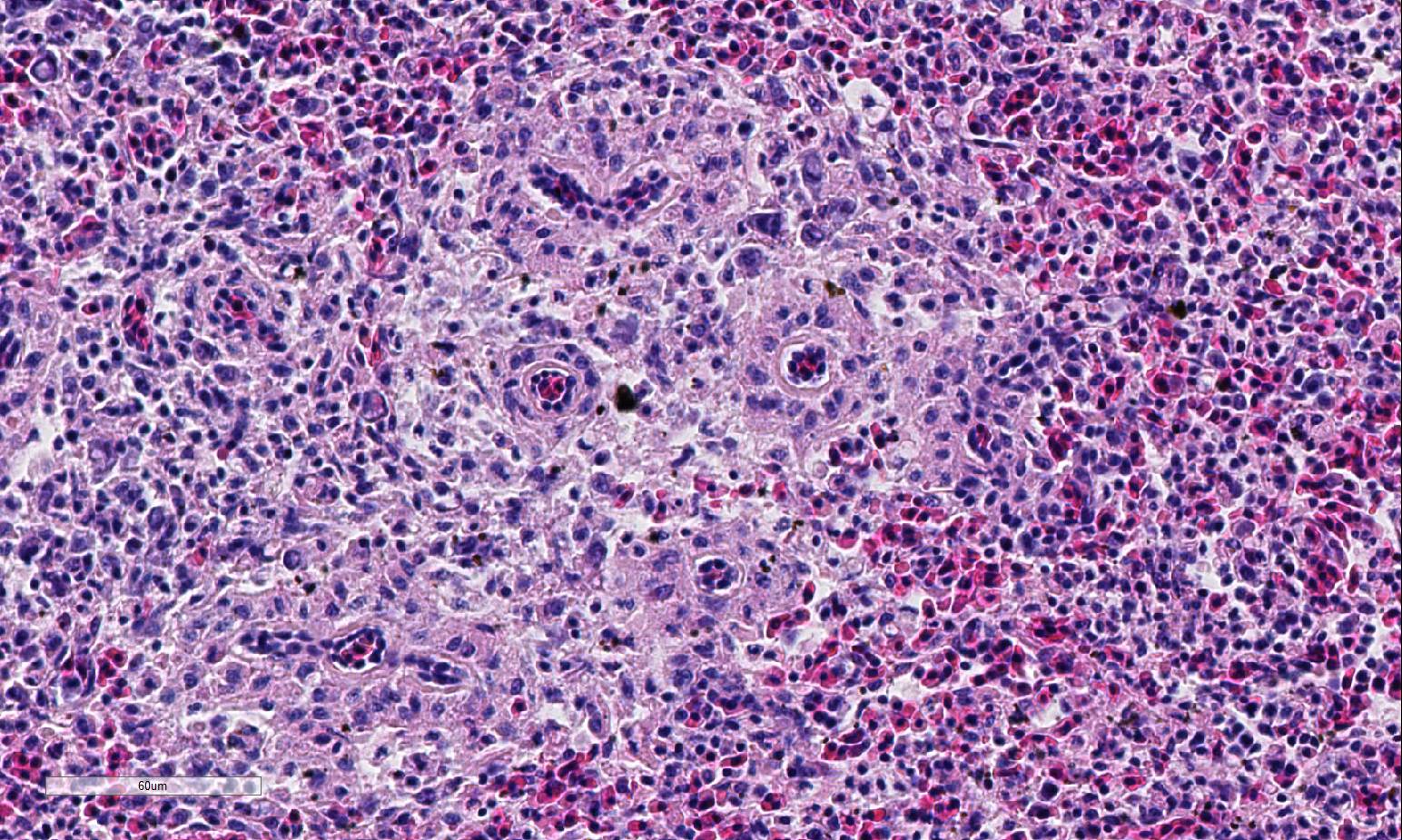

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Intestinal lesions and the scale of the mortality depends at least in part on the virulence of the THEV strain.9,10 THEV is classified as a type II adenovirus, of the family Adenoviridae, and has been further classified as a member of the more recently formed genus Si-adenovirus.1,4,11 It was originally identified in the USA, where it has been widely reported.11 The virus spreads via horizontal transmission including the oral route and rapidly replicates in the spleen of poults.12 A necrotizing splenitis is frequently described in the splenic white pulp13 with targeting of macrophages and particularly IgM-bearing B-lymphocytes.12,13 Infected B-lymphocytes and macrophages undergo both necrosis and apoptosis.9 Although the pathogenesis is incompletely understood infection of turkeys with virulent strains of THEV results in hemorrhage into the lumen of the duodenum and jejunum by erythrocytes diapedesis without obvious attendant vascular injury.9

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Adenoviruses of the Mastadenovirus genera include the majority of common mammalian adenoviruses and do not cause disease in avian species. The age of affected turkeys is approximately 4 weeks and older, with most infections occurring between 6 11 weeks; the course of clinical disease is approximately 7-10 days. Mortality rates may exceed 60%. Due to immunosuppression and secondary bacterial infections or co-infections, such as with E. coli, the course of disease and severity of losses can be exacerbated. Infection and recovery, as well as va-ccination, provides protection against subsequent challenge.8 It is postulated that persistent infection or latency may occur within macrophages or B-lymphocytes in birds infected with avirluent strains of THEV, which are used in live virus vaccines.2

The differential diagnosis list for the splenic lesions includes lymphoid neoplasia and bacteremia associated with infections such as E. coli, P. multocida and E. rhusiopathiae.8 A similar condition occurs in confinement-raised pheasants of approximately 3-8 months of age due to infection with an indistinguishable virus, and the condition is known as marble spleen disease (MSD). These two viruses are nearly genetically identical, although the pr-esentation of the disease in these respective species has some distinctions. In pheasants, MSD is characterized by diffuse necrotizing splenitis with hemorrhage and loss of architecture, but generally presents as a respiratory condition in naturally infected birds. Gross lesions may include congested lungs in addition to the splenic changes.8 THEV and MSD affect a slightly different age range of fowl but retain many similar features in regards to their effect on the spleen. Macrophages and B lymphocytes are the main target of both THEV and MSD as discussed above and although viral replication chiefly takes place within the spleen, virus may also be found in the intestine, bursa of Fabricius, thymus, liver, kidney and lung.

Conference participants described multifocal areas of pallor characterized by necrosis and loss of B lymphocytes within follicles / white pulp. There is extensive histiocytic infiltration of the spleen, primarily surrounding the vascular tree within the white pulp, and histiocytes frequently contain pale basophilic intranuclear viral inclusion bodies. Inclusion bodies are id-entified also within morphologically re-cognizable lymphocytes, although no IHC was performed to definitively establish the range of cell targets. The moderator com-mented about the histiocytic infiltration around splenic arteries, which is suggestive of the pathogenesis of THEV. The virus has a cytopathic effect on B lymphocytes and also replicates within macrophages, and transient immunosuppression occurs in infection by both virulent and avirulent strains.2,8 In response to infection, there is a large influx of macrophages, as well as T-lymphocytes in an attempt to clear the virus.8 Conference participants discussed the diagnosis of inflammatory splenitis vs. infiltrative and or necrotizing disease of the spleen. The moderator led a discussion around other features of THEV infection including the rapid clinical course and characteristic presence of hemorrhagic feces just prior to death, for which it is appropriately named. The hemorrhage is thought to be secondary to endothelial disruption and not due to viral destruction.2 Grossly, the spleen appears enlarged, friable and mottled.

References:

1. Beach NM, Duncan RB, Larsen CT, Meng XJ, Sriranganathan N, Pierson FW: Comparison of 12 turkey hemorrhagic enteritis virus isolates allows prediction of genetic factors affecting virulence. J Gen Virol. 2009; 90:1978-1985.

2. Beach NM, Duncan RB, Larsen CT, Meng XJ. Persistent infection of turkeys with an avirulent strain of turkey hemorrhagic enteritis virus. Avian Dis. 2009;53:370-375.

3. Davison AJ, Harrach B: Siadenovirus In: The Springer Index of Viruses, Tidona CA, Darai G, eds. Springer-Verlag: New York, NY; 29-33. 2002.

4. Davison AJ, Benko M, Harrach B. Genetic content and evolution of adenoviruses. J Gen Virol. 2003; 84:2895-2908.

5. Fitzgerald SD. Adenovirus infections. In: Swayne DE, ed. Disease of Poultry. 13th ed. Ames, IA: Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2013: 289-291.

6. Hafez HM. Avian adenoviruses infections with special attention to inclusion body

hepatitis/hydropericardium syndrome and egg drop syndrome. Pak Vet J. 2011; 31(2): 85-92.

7. Hess M, Raue R, Hafez HM: PCR for specific detection of haemorrhagic enteritis virus of turkeys, an avian adenovirus. J Virol Methods. 1999; 81: 199-203.

8. Pierson FW, Fitzgerald SD. Hemorrhagic enteritis and related infections. In: Swayne DE, ed. Disease of Poultry. 13th ed. Ames, IA: Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2013: 309-316.

9. Rautenschlein S, Sharma JM: Immunopathogenesis of haemorrhagic enteritis virus in turkeys. Dev Comp Immunol. 2000; 24:237-246.

10. Saunders GK, Pierson FW, van den Hurk JV. Haemorrhagic enteritis virus infection in turkeys: a comparison of virulent and avirulent virus infections, and a proposed pathogenesis. Avian Pathol. 1993; 22: 47-58.

11. Sharma JM. Hemorrhagic enteritis of turkeys. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1991; 30: 67-71.12. Suresh M, Sharma JM. Hemorrhagic enteritis virus induced changes in the lymphocyte sub-populations in turkeys and the effect of experimental im-munodeficiency on viral pathogenesis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1995; 45: 139-150.

13. Suresh M, Sharma JM. Pathogenesis of type II avian adenovirus infection in turkeys: in vivo immune cell tropism and tissue distribution of the virus. J Virol. 196; 70: 30-36.