Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

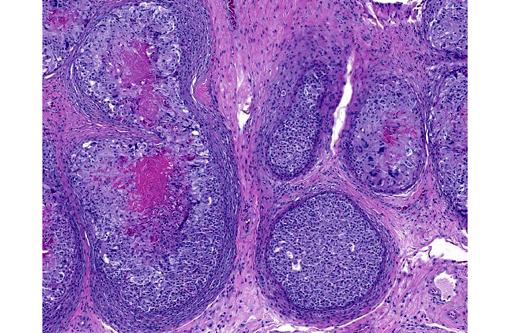

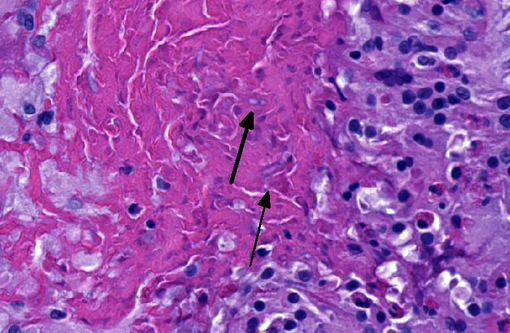

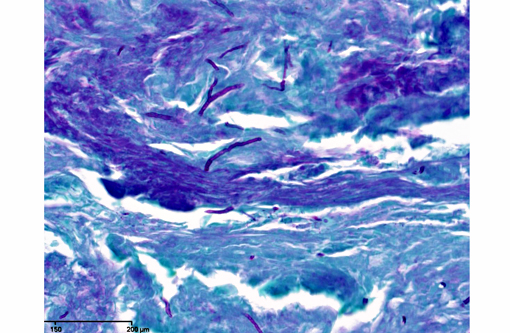

In sections of the ventral abdomen, deep layers of the epidermis contain multifocal, round, expansile aggregates of myriad fungal spores and hyphae. Fungal aggregates are primarily encased in dense keratin, and other times they are found clustered within the superficial stratum corneum. Fungal organisms are similar to those described above in the raised skin lesions. Commonly, arthroconidia are identified among the hyphae as well as free within the nearby epidermis. Epidermal changes surrounding the fungal aggregates include moderate dilation of intercellular spaces (spongiosis), ballooning degeneration, and mild transmigration of heterophils. Segmentally, in close proximity to the fungal organisms, the stratum corneum displays moderate orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. In the underlying dermis, there is moderate infiltrate composed mainly of heterophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages.Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Mycology culture: Chrysosporium sp. isolate.

PCR: Nannizziopsis guarroi based on DNA sequence analysis of the ITS and D1/D2 regions (performed at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center).

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The Nannizziopsis species seen most commonly in bearded dragons and green iguanas is N. guarroi.(1,2) The disease is often called Yellow Fungus Disease by hobbyists because the crusts found on bearded dragons tend to have yellow discoloration. Thus, crust formation, color change and necrosis are commonly seen in these cases. Lesions tend to be multifocal and may include the head, oral cavity, limbs, ventrum and dorsum. The infection is often aggressive, with extension into the subcutaneous tissues, muscles, and bones.(3) In some cases there is also systemic spread to the lungs and liver after local cutaneous invasion.(3)

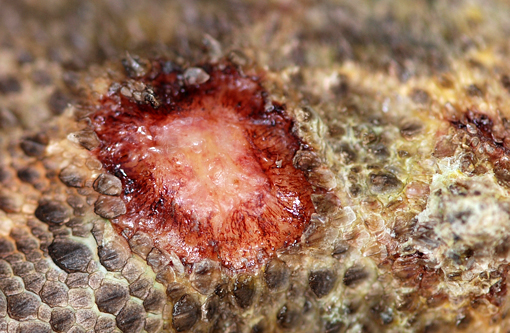

This inland bearded dragon had multifocal raised nodules on the skin, with multiple areas of ulceration and an irregular oval area of yellow discoloration on the ventral head, neck and abdomen, with no evidence of extension into underlying muscle and/or bone. Microscopically the raised nodules consisted of granulomatous proliferative dermatitis. Additionally, there was superficial ulceration with myriad intralesional segmented hyphae and arthroconidia, which by mycological culture and PCR were identified as Nannizziopsis guarroi.Â

Recently, morphologically similar isolates formerly referred to as members of the CANV complex, have been properly identified into three genera: Nannizziopsis, Paranannizziopsis, and Ophidiomyces, which are not particularly closely related within the Onygenales. The genus Nannizziopsis was split into 8 unique species: N. vriesii, N. dermatitidis, N. crocodili, N. barbata, N. guarroi, N. infrequens, N. hominis, and N. obscura. Benefits of this classification scheme include clarification of the range of susceptible hosts for each fungal species, monitoring trends of infection, determination of the prevalence of specific species in the environment, ability to evaluate species-specific antifungal efficacy, and development of specific strategies for disease prevention.(4)

N. guarroi is a keratinophilic ascomycetous fungus that has been associated with several cases of granulomatous dermatitis in toxicoferan squamates. Due to the inherent stress that may accompany classroom pets related to frequent handling and/or taunting, the role of stress cannot be ruled out in the susceptibility to the fungal infection in this case. N. guarroi do not grow at 40°C and hospitalizing reptiles at increased temperatures during treatment may help the patient eliminate the fungus. Additionally, laboratories may be underreporting N. guarroi infections if culture protocols call for temperatures in excess of 37°C (false negatives), stressing the importance of communication with laboratories in suspected N. guarroi cases.(2)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Fungi have used a nomenclature inconsistent with the rest of biology. There are separate genus and species names for asexual anamorph stages and sexual teleomorph stages of the same organism, resulting in multiple species names and paraphyletic taxa. In 2011, it was decided by the Nomenclature Section meeting of the International Botanical Congress that teleomorph names should be used (Hawksworth, 2011). This is problematic for medicine, as nearly all names of systemic fungi routinely used are anamorph names (e.g. Cryptococcus, Blastomyces, Histoplasma, Aspergillus, etc.). The anamorph genus Chrysosporium is widespread across the tree of the fungal order Onygenales, and contains organisms in more than 15 teleomorph genera, including Nannizziopsis. Many Chrysosporium sp. infecting reptiles have been morphologically misidentified as Chrysosporium anamorph of Nannizziopsis vriesii (CANV)

Recent publications have identified Nannizziopsis guarroi as the most common cause of yellow skin disease in bearded dragons.(1,5) This correlates with PCR findings in this case, and further illustrates the inaccuracy of the term CANV for this entity.Â

*Special thanks to Dr. Jim Wellehan, Asst. Professor at the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine for his contributions to this case*

References:

1. Abarca ML, Castella G, Martorell J, Cabanes FJ. Chrysosporium guarroi sp. nov. a new emerging pathogen of pet green iguanas (Iguana iguana). Med Mycol. 2010;48:365-372.

2. Abarca ML, Martorell J, Castell+�-� G, Ramis A, Caba+�-�es FJ. Der- matomycosis in a pet inland bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps) caused by a Chrysosporium species related to Nannizziopsis vriesii. Vet. Dermatol. 2009;20:295299.

3. Hawksworth DL. A new dawn for the naming of fungi: impacts of decisions made in Melbourne in July 2011 on the future publication and regulation of fungal names. MycoKeys. 2011;1: 720.

4. Par+�-� JA, et al. Pathogenicity of the Chrysosporium Anamorph of Nannizziopsis vriesii for veiled chameleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus). Medical Mycology. 2006;44:25-31.Â

5. Sigler L, et al. Molecular characterization of reptile pathogens currently known as members of Chrysosporium anamorph of Nannizziopsis vriesii complex and relationship with some human-associated isolates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2013;51:3338-3357.

6. Stchigel AM, Sutton DA, Cano-Lira JF, et al. Phylogeny of chrysosporia infecting reptiles: proposal of new family Nannizziopsiaceae and five new species. Persoonia. 2013;31:86-100.