Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 20

20 March, 2019

CASE III: Case 2 (JPC 4070611).

Signalment: 2 year 7 month old castrated male Labrador retriever, dog (Canis lupis familiaris).

History: This dog presented to the Queen Mother Hospital for Animals (Royal Veterinary College, UK) with a 4 month history of intermittent bloody discharge from his penis. The owner reported no problems with frequency, volume or the action of urination, nor did his urine appear to be discoloured. He had no previous history of illness aside from the presenting complaint. The dog had been imported from continental Europe. Urinalysis, blood biochemistry, and abdominal ultrasound were unremarkable. Haematology revealed a mild increase in lymphocytes, but was otherwise unremarkable.

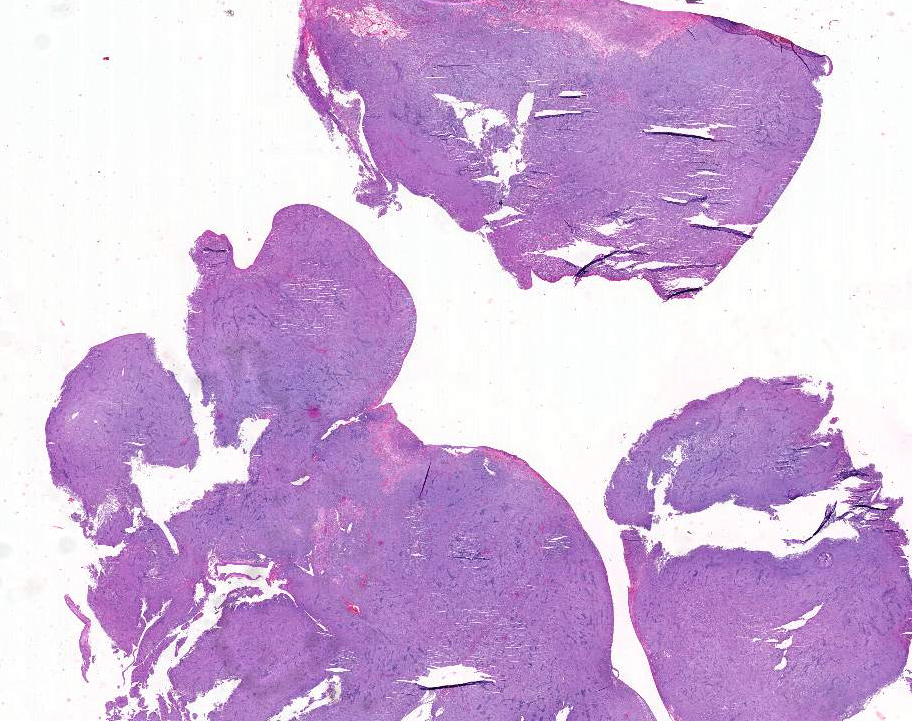

Gross Pathology: Physical examination revealed a smooth swelling at the base of the penis, which upon examination under general anaesthesia appeared to be a friable mass within the prepuce. The mass was removed and submitted for histopathologic examination.

Laboratory results: Cytologic examination of five impression smears reveals high nucleated cellularity, moderate amounts of blood and low numbers of lysed cells on a pale basophilic background. High numbers of round cells are found on all smears. Cells have a round to oval nucleus, 10-15um in diameter with finely to coarsely stippled chromatin, often a single large, round, prominent nucleolus and moderate amounts of pale blue cytoplasm, frequently containing moderate numbers of punctate vacuoles. Cells display mild to moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, with low numbers of mitotic figures and rare binucleated forms. Low to moderate numbers of small lymphocytes are focally admixed with the tumour cells. Two smears additionally contain moderate to high numbers of squamous epithelial cells in sheets and individually, often displaying dyskeratosis. Squamous cells display mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, occasional bi- and rare multinucleation, and occasionally prominent nucleoli. Also occasional cells have prominent perinuclear vacuolation. These two smears also focally contain high numbers of variably degenerate neutrophils, occasionally containing intracellular cocci. Low numbers of macrophages are also found. These features are consistent with transmissible venereal tumour, with septic neutrophilic inflammation and squamous dysplasia. Other round cell tumours (e.g. of histiocytic origin) cannot be ruled out completely, but far less likely. Septic inflammation and squamous dysplasia are likely secondary changes to the presence of the tumour (e.g. ulceration).

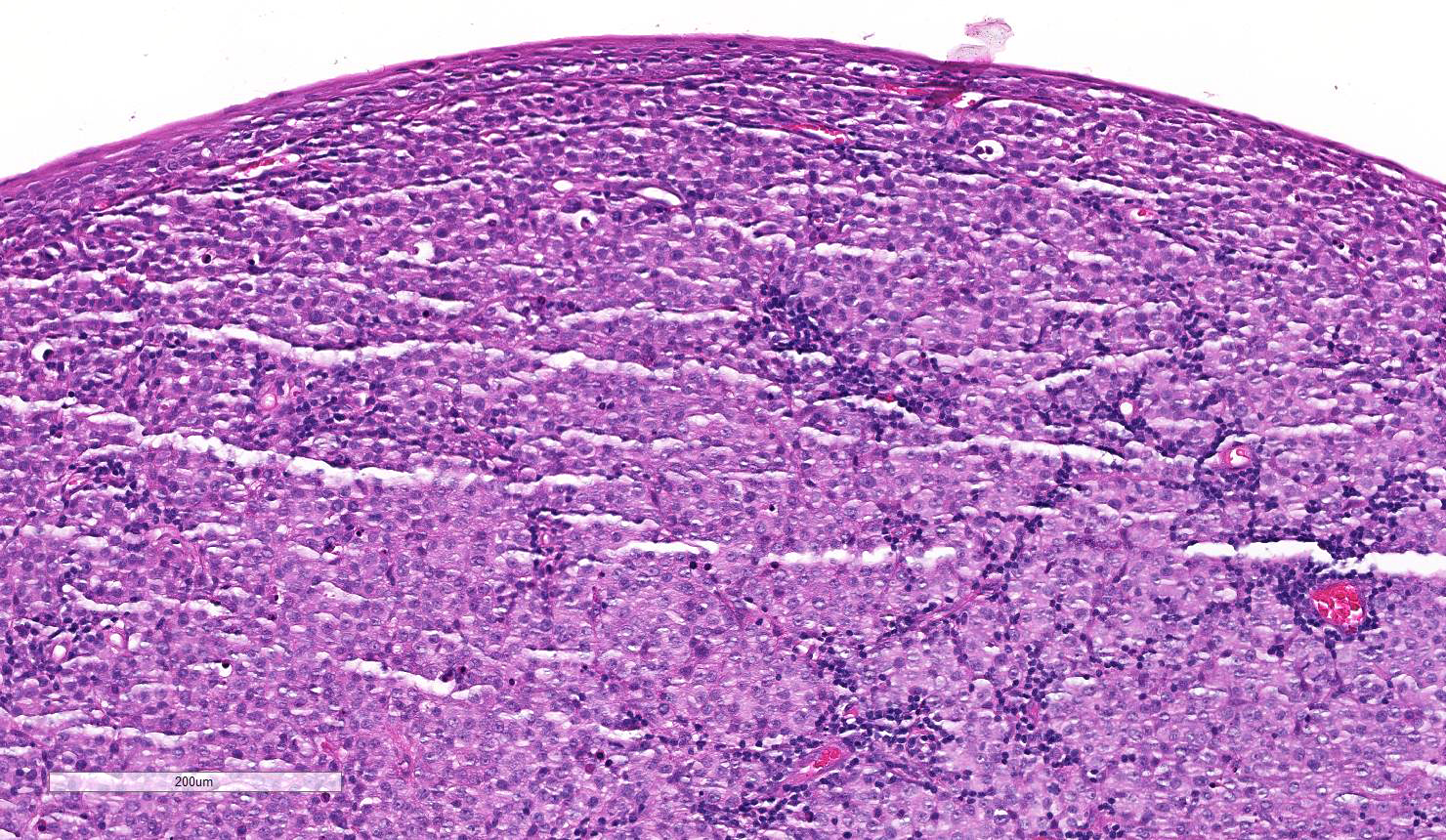

Microscopic Description:

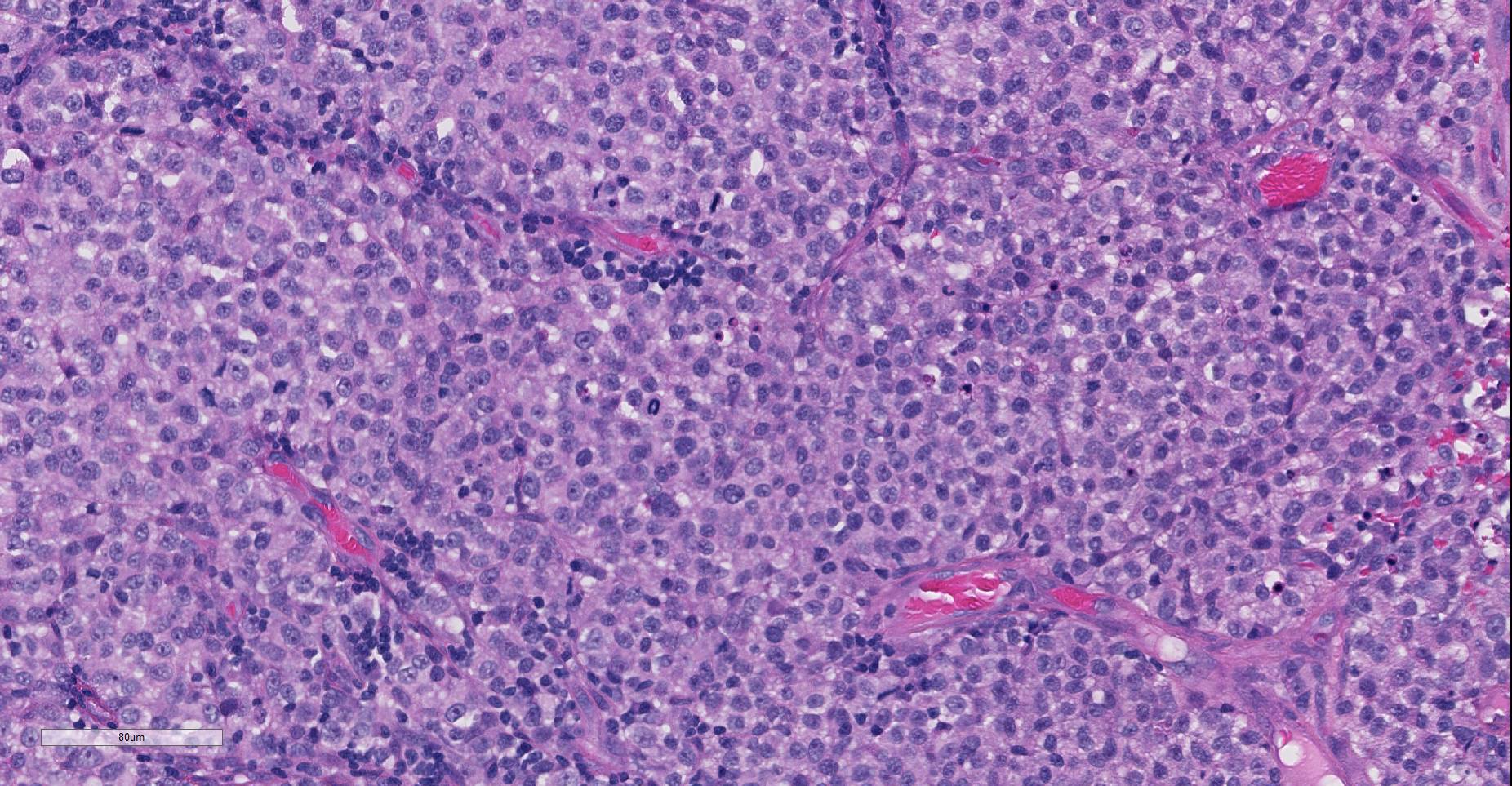

Multiple sections of non-haired skin, from the prepuce per history, are examined. Effacing the lamina propria, raising a multifocally eroded and attenuated stratified squamous epithelium, and extending to the lateral and deep borders of the examined sections, is an unencapsulated, poorly demarcated, round cell neoplasm. The cells are arranged in sheets and loose cords amongst a scant fibrovascular stroma. The neoplastic cells are round with indistinct cell borders, a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm containing small clear vacuoles, a central round nucleus with stippled or peripheralised chromatin, and a single prominent magenta nucleolus. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are mild, and 42 mitoses are observed in 10 high power (x400) fields, some of which are bizarre. Multifocally the tumour is infiltrated by moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Moderate to high numbers of extravasated erythrocytes and fibrin (haemorrhage) are present beneath the epithelium multifocally.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Prepuce; Transmissible venereal tumour.

Contributor’s Comment: Histopathologic and cytologic examination reveals a canine transmissible venereal tumour (CTVT). The cell of origin in CVTVs is unknown,1 however a histiocytic origin is suspected due to positive immunolabelling for lysozyme, ACM1, a-1-antitrypsin and vimentin, and negative immunolabelling for keratin, desmin a-smooth muscle actin, CD3, lgG and lgM, and A and K light chains.10,13 CTVT should always be considered in cases of genital round cell tumours and primary differentials are other round cell tumours of the skin, such as histiocytoma, lymphoma and poorly granulated mast cell tumour.5 Haematoxylin and eosin differentiation between histiocytomas and CTVTs can be challenging, and cytology should be used, as in this case, to help confirm the diagnosis because of better nuclear preservation in cytologic preparations.5

CTVT is the most common tumour of the penis of dogs,7 and typically affects the proximal part of the penis.3 The tumour typically presents as a single or multinodular mass4 with a red ulcerated surface.5 Although primarily located on the genitalia,5 tumours can also arise on the oral, nasal or conjunctival mucosa.7 Less commonly the skin is involved,7particularly sites which can come into contact with the genitalia.5 Dogs of both sexes and all ages can be affected, and it is most common in the dorsal vagina15 of sexually mature female dogs.5 The pathogenesis is by physical transplantation rather than infectious means, and usually occurs during coitus.5 This is thought to be due to abrasions and bleeding of penile and vaginal mucosa during coitus increasing the chance of transplantation.13 Similar to canine cutaneous histiocytomas, the tumour has a predictable growth pattern of progressive growth, a static phase, and then regression after one to two months.10,13 Lymphoplasmacytic infiltration is a feature during regression7 and can be used to distinguish from lymphoma.5,13 Metastasis is rare, but has been reported in immunosuppressed animals and puppies. Metastases to the inguinal lymph nodes, brain, adenohypophysis, liver, and kidneys have been reported.6,13

The global distribution of CTVT is unexplained, and is previously unreported in the UK.5 Two subclades of CTVT have been identified, each of which now has a broad geographic distribution.5The host does not contribute to the growth of the tumour.7

The neoplastic cells have 59 rather than the usual 78 chromosomes present in the cells of dogs, and this karyotypic variation is consistent between CTVTs of different animals.7 A 1.5kbp repetitive insertion has been identified upstream of c-myc in all CTVTs.7 Further investigation has revealed that CTVT first arose from a common ancestral neoplastic cell in a wolf or dog related to 'old' East Asian breeds.13 This is thought to have occurred 200 to 2500 years ago, thus CTVT may represent the oldest known mammalian somatic cell in continuous propagation.13 CTVT can be transmitted between other canids, including foxes, coyotes, jackals and wolves.13 Dogs appear to be resistant to challenge after natural regression of the tumour.15

CTVT was the first tumour to be transmitted experimentally, by Novinsky in 1863.15 In 1965, a transmissible sarcoma, both spontaneous and induced by 20-methylcholanthrene, in Syrian hamsters was successfully transmitted experimentally between individuals without immunosuppression of the host.2 Two other transmissible tumours have also been identified. Devil facial tumour disease is a transmissible tumour of the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisi). lmmunohistochemical profiling has demonstrated a Schwann cell origin of this monophyletic clonally transmissible tumour.11 A Schwann cell specific myelin protein, periaxin (PRX), is used as a diagnostic marker for devil facial tumours.11 Finally, a clonal contagious leukaemia in soft shelled clams (Mya arenaria) exhibits characteristics similar to CTVT: The genotype of neoplastic cells does not match the host animal, and there is near identical genotype of neoplastic cells between affected animals despite geographic separation, highly suggestive of horizontal transmission of leukaemia in these clams.8

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathology and Pathogen Biology, The Royal Veterinary College, University of London. http://www.rvc.ac.uk/pathology-and-diagnostic-laboratories

JPC Diagnosis: Prepuce: Transmissible venereal tumor.

JPC Comment: Transmissible venereal tumor occupies a unique niche in cancer biology as the most well-characterized of a small subset of neoplasms which is transmitted as living cells between hosts, rather than transformation of the host’s cells.1 The contributor has provided an excellent review of this tumor and other transmissible tumors in animal species.

The tumor, which has been reported under several names, to include transmissible venereal sarcoma, venereal granuloma, infectious sarcoma, and Sticker’s sarcoma, was first described by Hujard in 1920.4 In 1876, the Russian veterinarian Novinsky demonstrated the nature of the tumor with the first transplantation experiments.4

A 2015 paper by Setthawongsin et al16 detailed molecular identification of the specific long interspersed element (LINE) inserted upstream of the c-myc gene in CTVT cells via PCR on frozen tissue. The moderator discussed recent development of a PCR test for paraffin-embedded tissue utilizing primers of less than 100 bp which is now publicly available through the Michigan State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, which may be of utility in diagnosing neoplasms not present in traditional genital locations.

The moderator also compared cytologic versus histologic appearance of these neoplasms. When taken in context of being from the genital area, the diagnosis of CTVT is not especially difficult. In this particular sample, the cytologic appearance with traditional round centrally placed nuclei, prominent, often single nucleoli, and the presence of lymphocytes and plasma cells often in perivascular location is very characteristic of this particular neoplasm. Cytologically, the presence of numerous vacuoles within the blue cytoplasm of round cells is also a fairly characteristic finding in CTVT, and some pathologists prefer cytology over histology for their diagnosis.

CTVT has evolved a number of mechanisms to evade the host response. Tumor cells downregulate DLA class II expression, but express just enough (10%) of DLA class I genes (complete masking of DLA Class I genes actually activates natural killer cells).4 TVT cells can also secrete immunosuppressive levls of transforming growth factor-β. During the period of regression, host IL-6 liberated from infiltrating lymphocytes works with host IFN-γ to re-establish DLA expression.4

Since the submission of this report, other clonally transmitted tumors have been reported in bivalves, including bay mussels (Mytilus trossulus), cockles (Cerastoderma edule) and golden carpet shell clams (Polititapes aureus).9 Interestingly, the neoplasm in golden carpet shell clams appears to have arisen in another species, the pullet carpet shell (Venerupis corugata).9 Even more interesting is a 2015 report by Muelenbachs et al.14 of pulmonary and lymph node neoplasms in a 41-year-old HIV-positive individual with concurrent Hymenolepis nana infection. Neoplasms composed of small, rapidly dividing cells uncommon in human pathology were determined, after a CDC consultation, the neoplasms were determined to contain DNA of H. nana.14

References:

- Agnew DW, MacLachlan NJ. Tumors of the Genital System. In Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Species. Ames IA, Wiley Blackwell, pp 718-720.

- Fabrizio AM. An induced transmissible sarcoma in hamsters: Eleven-year observation through 288 passages. Cancer Res 1965; 25:107-117.

- Foster RA. Male reproductive system. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD (eds.) Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease: 5th ed. Missouri, USA: Elsevier;2012: 1152.

- Ganguly B, Das U, Das AK. Canine transmissibl veneral tumour: a review. Comp Oncol 2013; 14(1):1-12.

- Goldschmidt MH, Hendrick MJ. Tumours of the skin and soft tissues. In: Meuten DJ (ed.) Tumors in Domestic Animals: 4th ed. Iowa, USA: Iowa State Press;2002:115-117.

- Joint Pathology Centre, Wednesday Slide Conference; 2007: 10, Case 2.

- Kennedy PC, Cullen JM, Edwards JF, et al (eds.) Histological Classification of Tumors of the Genital System of Domestic Animals: Second Series Volume IV. Washington D.C., USA: AFIP, WHO;1998:8.3 and 11.3

- Metzger MJ, Reinisch C, Sherry J, Goff SP. Horizontal transmission of clonal cancer cells causes leukemia in soft-shelled clams. Cell 2015; 161 :255-263.

- Metzger MJ, Villalba A, Carballal MJ, Iglesias D, Sherry J, Reinisch C, Muttray AF, Baldwin SA, Goff SP. Widespread transmission of independent cancer lineages within multiple bivalve species. Nature 2016; 534(7609): 705-709.

- Mozos E, Mendez A, Gomez-Villamandos JC, Martin de las Mulas J, Perez J. lmmunohistochemical characterization of canine transmissible venereal tumor. Vet Pathol 1996; 33:257-263.

- Murchison EP, Tovar C, Hsu A. The Tasmanian devil transcriptome reveals Schwann cell origins of a clonally transmissible cancer. Science 2010; 327:84-87.

- Murgia C, Pritchard JK, Kim SY, Fassati A, Weiss RA. Clonal origin and evolution of a transmissible cancer. Cell 2006; 126(3):477-487.

- Mukaratirwa S, Gruys E. Canine transmissible venereal tumour: cytogenetic origin, immunophenotype, and immunobiology. A review. Vet Quarterly 2003; 25(3):101-111.

- Muelenbachs A, Bhatnagar J, Agudelo CA, Hidron A, Eberhard ML, Mathison BA, Frace H, Ito K, Metcalfe MG, Rollin DC, Visvesvara GS, Pham CD. Malignant Transforamtion of Hymenolepis nana in a Human Host. N Engl J Med 2014; 373:1845:1852.

- Schlafer DH, Miller RB. Female genital system. In: Grant Maxie M (ed.) Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals: 5th ed. Saunders Elsevier;2007:547-548.

- Setthawaontsin C, Techangamsuwan S, Tankkawaattana S, Rungsippat A. cell-based polymerase chain reaction for canine transmissible venereal tumor diagnosis. Vet Med Sci