Signalment:

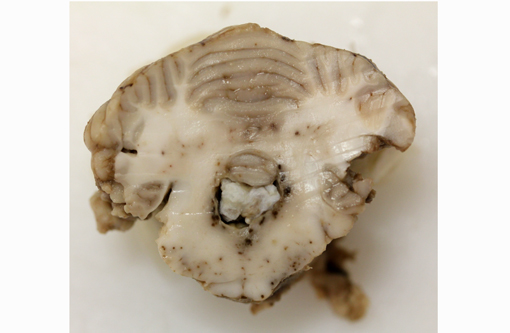

Gross Description:

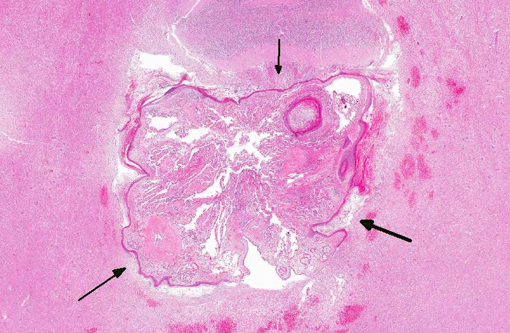

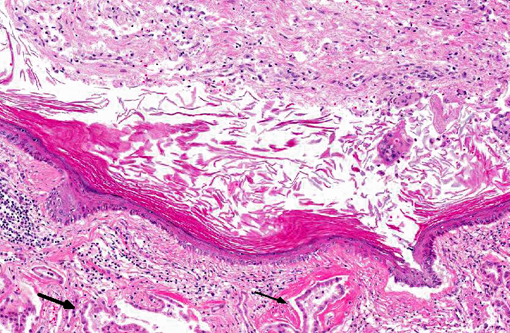

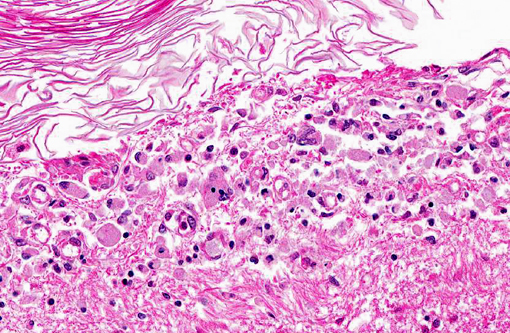

Histopathologic Description:

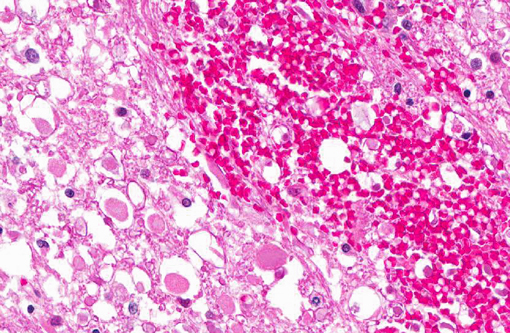

Intercellular bridges between keratinized cells are prominent. There are approximately five mitoses per 400x field with frequent bizarre mitotic figures. There is severe anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. Multifocally within the neoplasm there are large areas of necrosis, hemorrhage and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils and some macrophages. Many submucosal and subserosal vessels contain clusters of neoplastic cells (tumor emboli) as well as fibrin thrombi. Overlying the ulcerated mucosa, there is abundant fibrillar eosinophilic material (fibrin exudation) and hemorrhage, admixed with cellular and karyorrhectic debris (necrosis) and bacterial colonies. Throughout the mass, but especially along the serosa, there are multiple nodules or bands of abundant fibrous connective tissue (scirrhous response).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In humans, intracranial epidermoid cysts are a well-recognized entity and are thought to comprise up to 1.8% of all intracranial masses.(7) Epidermoid cysts of the CNS are uncommon in domestic animals with a handful of cases being reported in dogs, horses, mice, and rats.(2,4,9,10) In dogs, epidermoid cysts have been reported within the cranial cavity(4,6,11,12) and within the vertebral canal.(1,4) Intracranial masses are most common.Â

There are too few reports of intracranial epidermoid cysts in dogs to reliably identify a breed or sex predilection. Dogs with intracranial epidermoid cysts have ranged in age from 3 months to 8 years with the majority of dogs being less than 2 years old.(4) These findings may suggest a predilection for young dogs, and could be consistent with the presence of a congenital lesion. Intracranial epidermoid cysts are slow growing masses and in people typically do not cause clinical signs until fifth decade of life.(4) The slow, linear growing pattern of these masses may explain the wide age range reported in dogs for a purportedly congenital lesion.

Intracranial epidermoid cysts exhibit an expansile growth pattern through desquamation and accumulation of keratin.(7) While these lesions may be found as incidental findings at necropsy,(4) intracranial epidermoid cysts may cause clinical signs referable to compression of adjacent structures resulting in focal neurologic dysfunction or obstruction of CSF resulting in hydrocephalus.(4,6,11,12) In both humans and dogs, epidermoid cysts have a predilection for the caudal fossa which may be a reflection of the initial closure of the neural tube in the rhombencephalon. In dogs, intracranial epidermoid cysts have been reported in the fourth ventricle and cerebellopontine angle.(4) Based on their location in the caudal fossa, canine epidermoid cysts are frequently associated with vestibular and occasionally cerebellar signs.(4,6) In addition to the space occupying nature of these lesions, other sequelae reported in people include the development of chemical meningitis, and rarely malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma.(7,8) Malignant transformation has not been reported in dogs, and in the current case there was no evidence of squamous cell carcinoma in the sections examined.

Pathologic features of intracranial epidermoid cysts are similar to those that are routinely encountered in the skin. Microscopic examination reveals the presence of a cyst lined by stratified squamous epithelium supported by connective tissue stroma and surrounding keratin. Portions of choroid plexus are often adhered to or are incorporated into the cyst.(4) Intracranial dermoid cysts have also been reported and also arise from the inappropriate inclusion of nonneural ectoderm in the CNS. Dermoid cysts can be differentiated from epidermoid cysts in that the former is lined by adnexal structures such as hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands.(4) These features were not observed in the current mass favoring a diagnosis of epidermoid cyst over dermoid cyst.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Participants also examined dermoid cysts as a related, but more frequent finding in the CNS of dogs. Like their non-congenital, dermal counterparts, both epidermoid and dermoid intracranial cysts are lined by stratified squamous epithelium. Although they have a similar embryologic origin, the dermoid cyst is derived from a more pluripotent precursor cell and often produces adnexal structures, such as sebaceous glands, apocrine glands or hair follicles.(6) Additionally, Rhodesian ridgeback dogs that carry the autosomal dominant dorsal ridge trait have been shown to be predisposed to the congenital cutaneous defect known as dermoid sinus, which is a draining sinus at the dorsal midline that occasionally communicates with the subarachnoid space.(3) Typically these dogs do not have any clinical problems.Â

Intracranial epidermoid cysts occur in other veterinary species; in mice they often occur within the leptomeninges of the lumbar/sacral spinal cord or (less commonly) associated with the fourth ventricle.(2) There are generally no clinical signs in mice or rats with this lesion, which may be an indication that the cysts do not grow large enough to compress adjacent structures.(2) Intracranial epidermoid cysts in mice are thought to be strain dependent and are typically interpreted as incidental findings. Conversely, dermoid cysts in mice have rarely been associated with clinical neurologic dysfunction.(2) Epidermoid cysts have not been reported in the CNS of hamsters or cats.

References:

2. Hansmann F, Herder V, Ernst H, et al. Spinal epidermoid cyst in a SJL mouse: case report and literature review. J Comp Pathol. 2011;145:373-377.

3. Hillbertz NH, Andersson G. Autosomal dominant mutation causing the dorsal ridge predisposes for dermoid sinus in Rhodesian ridgeback dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2006;47(4):184-188.

4. Kornegay JN, Gorgacz EJ. Intracranial epidermoid cysts in three dogs. Vet Pathol. 1982;19:646-650.

5. Lipitz L, Rylander H, Pinkerton ME. Intramedullary epidermoid cyst in the thoracic spine of a dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2011;47:e145-e149.

6. MacKillop E, Schatzburg SJ, de Lahunta A. Intracranial epidermoid cyst and syringohydromyelia in a dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2006;47:339-344.

7. Michael II LM, Moss T, Madhu T, et al. Malignant transformation of the posterior fossa epidermoid cyst. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19:505-510.

8. Netsky MG. Epidermoid tumors. Surg Neurol. 1988;29:477-483.

9. Nobel TA, Nyska A, Pirak M, et al. Epidermoid cysts in the central nervous system of mice. J Comp Pathol. 1987;97:357-359.

10. Peters M, Brandt K, Wohlsein. Intracranial epidermoid cyst in a horse. J Comp Pathol. 2003;12:89-92.

11. Platt SR, Chrisman CL, Adjiri-Awere A, et al. Canine intracranial epidermoid cyst. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 1999;40:454-458.

12. Steinberg T, Matiasek K, Bruhschwein A, et al. Imaging diagnosis-intracranial epidermoid cyst in a Doberman Pinscher. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2007;48:250-253.