Results

AFIP Wednesday Slide Conference - No. 12

10 December 1997

-

- Conference Moderator: MAJ Mark Mense

Diplomate, ACVP

Division of Pathology

Walter Reed Army Institute of Research

Washington, D.C. 20307-5100

-

- Return to WSC Case Menu.

Case I - W751-97 (AFIP 2597489)

-

- Signalment: Adult, male, wild rabbit.

-

- History: The animal was found dead adjacent to the

clinical staff offices. Deaths in feral rabbits in the vicinity

of the Clinical Center had been noted several days previous to

this animal being found.

-

- Gross Pathology: There were no external lesions. The

cadaver appeared fresh and internal lesions were limited to the

lungs which were diffusely edematous and contained multifocal

hemorrhages, and the spleen which was enlarged approximately

twice normal size and was dark. The liver was enlarged with an

accentuated pale lobular pattern.

-

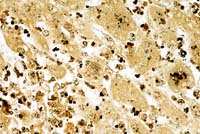

- Laboratory Results: Immunohistochemistry on sections

of liver was positive for rabbit calicivirus.

-

- Contributor's Diagnoses and Comments:

- 1. Hepatitis, acute, zonal, periportal to midzonal, necrotizing,

severe.

- 2. Splenitis, acute, necrotizing, massive, with hemorrhage

and thrombosis.

- 3. Lung, intravascular fibrinous thrombosis, multifocal,

acute with minimal interstitial changes, rabbit calicivirus (rabbit

hemorrhagic disease).

-

- This case is typical for the disease in susceptible adult

rabbits, and is almost uniformly fatal. Many animals are found

dead without premonitory signs, and those found alive rapidly

become comatose and die quietly. Blood-stained frothy fluid may

exude from external nares, and the lungs are edematous. Typically,

there is complete destruction of the sinusoidal architecture

of the liver and spleen, and replacement by fibrinous coagulum

containing erythrocytes. Destruction of white pulp may occur

as in this case, but is not uniformly present and may be secondary

to stress rather than a direct effect. Acute coagulation necrosis

in the liver is typically periportal, extending to midzonal areas

as in this case, and is usually accompanied by a minimal inflammatory

response.

- Viral antigen can be localized to areas of splenic and hepatic

necrosis using immunohistochemical methods, and the virus appears

to specifically target sinusoidal lining cells in these organs.

Although thrombi are often found in the lungs and also occasionally

in other organs, these are not associated with localization of

viral antigen in affected vessels by immunohistochemistry, although

viral antigens can be recovered from tonsils, lymph nodes and

kidneys using more sensitive methods such as RT-PCR. Intravascular

thrombosis is thought to cause rapid death, but histopathologic

evidence of DIC may wane if necropsies are delayed for long after

death. DIC is thought to develop largely because of the severe

necrosis of the liver.

- Rabbit hemorrhagic disease caused devastating losses of farmed

rabbits in Europe and Asia beginning in 1984. Baby rabbits do

not support viral replication to the degree that is found in

adults, and younger rabbits (<4 weeks) do not develop overt

signs after calicivirus infection. After extensive research,

the virus was released into Australia as a biologic method for

control of feral rabbits and although marked reduction in rabbit

numbers has occurred in some areas as a result, in other areas

rabbit numbers appear to have returned to pre-release levels.

Reasons for this remain unclear. Overseas, a non-pathogenic strain

of rabbit calicivirus has been identified and infection with

this strain may protect against the pathogenic isolate. In addition,

antibody is protective and exposure of young kits to the virus

may allow the establishment of immunity. Possible spread of the

virus by fomites, birds and insect vectors is suspected, but

in the unusual circumstances in Australia, where upon release/escape

in late 1995, cases were recorded up to hundreds of miles away

within days, and deliberate spread by the farming community was

suspected.

- A related calicivirus, European brown hare syndrome virus,

produces a similar disease in hares, but the two diseases are

distinct entities and cross infection or protection do not occur.

These two viruses are unlike other members of Caliciviridae (San

Miguel sea lion virus and feline calicivirus) in that they appear

to have little genomic variation between isolates. An effective

vaccine is available for use in laboratory, commercial and companion

rabbits and vaccination of these rabbit stocks in Australia was

possible prior to release of the virus. The use of rabbit calicivirus

as a biologic method of controlling a massive population of feral

rabbits precipitated intense debate. Because the virus kills

rabbits so quickly and moribund animals generally die quietly,

objections based on animal ethical grounds were largely dismissed.

Controversy remains as to whether the depletion of feral rabbit

numbers will have a beneficial effect on threatened native wildlife

species, because recovery of degraded habitats may be offset

by greater predation of these species by feral cats and foxes

that normally rely on rabbits as their major food source.

-

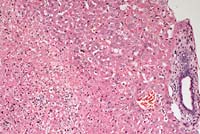

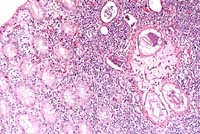

- Case 12-1. Liver. Acute necrosis with intact parenchyma.

10X

- AFIP Diagnoses:

- 1. Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, acute, periportal to midzonal,

diffuse, moderate, rabbit, lagomorph.

- 2. Lung: Fibrin thrombi, multifocal, with mild acute interstitial

pneumonia.

- 3. Lung, blood vessels: Medial hypertrophy, multifocal, moderate.

- 4. Spleen: Congestion, hemorrhage, and fibrin deposition,

acute, diffuse, severe, with lymphoid necrosis.

-

- Conference Note: Rabbit hemorrhagic disease (RHD)

virus affects rabbits of the species Oryctolagus cuniculus; no

other rabbit species have been shown to be susceptible.9 The

incubation period is 16-48 hours. Originally, reports from China

identified peracute, acute, and subacute forms of the disease.

Subsequent descriptions in both natural and experimental infections

have been consistent with a peracute form, in which rabbits die

suddenly with few or no clinical signs, and an acute form, which

is seen in areas where RHD is established and in which rabbits

exhibit clinical signs before death.

- RHD virus is spread by several routes and vectors. The virus

is present in excretory products, and enters susceptible hosts

usually by the oral or respiratory routes. The virus is stable

in the environment, and can be spread by fomites such as bedding

material or feedstuffs, or carried short distances by insects.

Foxes and polecats have been shown to seroconvert after ingestion

of the virus, though their role in transmission of the disease

is unclear. Rabbit products, including pelts and meat, serve

as potential sources of spread. An RHD epidemic in Mexico was

linked circumstantially to frozen rabbit carcasses imported illegally

through another country, though direct confirmation of disease

transfer from infected meat products was never demonstrated.9

- Comparatively, RHD resembles certain viral hemorrhagic diseases

of humans and nonhuman primates, including Lassa fever, simian

hemorrhagic fever, and Ebola and Marburg viral infections. The

pathogenic mechanisms of DIC in these diseases are not completely

understood.

-

- Contributor: School of Veterinary Science, The University

of Melbourne, 250 Princes Highway, Werribee, Victoria 3030, Australia

-

- References:

- 1. Brander P, Boujon CE, Bestetti GE: Infectious hemorrhagic

disease of rabbits in the Bern Pathology Institute (1988-1990):

season and regional distribution and histopathological findings.

Schweiz-Arch-Tierheilkd. 134(8):383-389, 1992.

- 2. Capucci L, Fusi P, Lavazza A, Pacciarini ML, Rossi C:

Detection and preliminary characterization of a new rabbit calicivirus

related to rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus but nonpathogenic.

J Virol 70(12):8614-8623, 1996.

- 3. Chasey D, Lucas M, Westcott D, Williams M: European brown

hare syndrome in the U.K.; a calicivirus related to but distinct

from that of viral hemorrhagic disease in rabbits. Arch Virol

124(3-4):363-370, 1992.

- 4. Fuchs A, Weissenbock H: Comparative histopathological

study of rabbit hemorrhagic disease (RHD) and European brown

hare syndrome (EBHS). J Comp Pathol 107(1):103-113, Jul 1992.

- 5. Guittre C, Ruvoen-Clouet N, Barraud L, Cherel Y, Baginski

I, Prave M, Ganiere JP, Trepo C, Cova L: Early stages of rabbit

hemorrhagic disease virus infection monitored by polymerase chain

reaction. Zentralbl-Veterinarmed-B 43(2):109-118, Apr 1996.

- 6. Ueda K, Park JH, Ochiai K, Itakura C: Disseminated intravascular

coagulation (DIC) in rabbit hemorrhagic disease. Jpn-J-Vet-Res

40(4):133-141, Dec 1992.

- 7. Wirblich C, Thiel HJ, Meyers G: Genetic map of the calicivirus

rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus as deduced from in vitro translation

studies. J Virol 70(11):7974-7983, Nov 1996.

- 8. Park JH, Lee Y-S, Itakura C: Pathogenesis of acute necrotic

hepatitis in rabbit hemorrhagic disease. Lab Anim Sci 45(4):445-449,

1995.

- 9. Chasey D: Rabbit haemorrhagic disease: the new scourge

of Oryctolagus cuniculus. Laboratory Animals 31:33-44, 1997.

-

- International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #14546

-

Case II - 95051363 (AFIP 2596338)

-

- Signalment: 23-day-old, female, Quarter Horse.

-

- History: This foal appeared depressed and icteric

at 6:30 a.m. and was found dead at 12:30 p.m.

-

- Gross Pathology: The foal was moderately icteric.

The stomach had multiple small foci of ulceration in the non-glandular

region. The liver was moderately enlarged with rounded edges.

On cut surface, the liver bulged, the lobular pattern was accentuated,

and the liver was yellow.

-

- Laboratory Results: Bacteriology results: Only a few

contaminating bacteria (E. coli and Enterobacter sp.) were isolated

from the liver.

-

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Liver, hepatitis,

suppurative, with necrosis, multifocal, coalescing, severe, compatible

with Tyzzer's disease of neonatal foals.

- Intracellular bacteria compatible with Clostridium piliforme

(Bacillus piliformis) were demonstrated in histopathological

sections. Lesions and organisms are compatible with Tyzzer's

disease in foals.

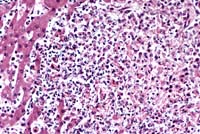

- Case 12-2a. Liver. Locally extensive hepatic necrosis

with an influx of neutrophils. 20X

- Case 12-2b. Liver. Note the intracellular cluster

of long slender bacilli (Clostridium piliformis). Warthin-Starry

40X

AFIP Diagnoses:

- 1. Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, neutrophilic, acute, multifocal

to coalescing, random, severe, Quarter Horse, equine.

- 2. Liver: Cholestasis, canalicular, multifocal, moderate.

-

- Conference Note: Tyzzer's disease is an acute, highly

fatal, epizootic enterohepatic disease of neonatal or weanling

animals. It has been reported in numerous animal species, including

horses, cattle, mice, rats, hamsters, guinea pigs, rabbits, foxes,

and coyotes. The causative agent, Clostridium piliforme, is a

gram-negative, spore-forming, motile, obligate intracellular

bacterium with peritrichous flagella. The vegetative form causes

the disease state, and appears as bundles or "haystacks"

within its target cells, i.e. enterocytes and hepatocytes. Visualization

of the bacteria in histologic section is enhanced with silver

stains such as the Warthin-Starry procedure.

- In horses, Tyzzer's disease usually affects one- to six-week-old

foals. Clinical signs include weakness, rapid respiratory rate

and pulse, cold extremities, icterus, blindness, and severe depression

before death, which occurs within 2 to 48 hours. Diarrhea may

also be observed. Outbreaks of the disease are sporadic, typically

affecting very few animals in a herd. This suggests that the

disease is not highly contagious, and may be limited to immunocompromised

foals.1

- The pathogenesis of equine Tyzzer's disease is incompletely

understood. Clostridium piliforme is transmitted by the fecal-oral

route. The initial site of infection is the intestinal epithelium,

from which the organism is transported hematogenously to the

liver. In rodents, transplacental transmission also occurs, but

this has not been demonstrated in the horse.

- Gross lesions include icterus, hepatomegaly, and multifocal

1- to 5-mm white foci scattered throughout the hepatic parenchyma.

In guinea pigs, mesenteric and colonic lymph nodes are swollen,

and the cecum and colon are reddened, thickened, distended, and

contain gray pinpoint necrotic foci. Similar lesions can be found

in hamsters, but in this species the most striking gross lesion

reported is multiple white elevated nodules in the heart, which

are necrotic foci with massive infiltrates of large macrophages,

neutrophils, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts interspersed

with the organisms.

-

- Contributor: Department of Anatomy, Pathology and

Pharmacology, 250 Veterinary Medical Bldg., Oklahoma State University,

Stillwater, OK 74078-2007.

-

- References:

- 1. Hook RR, Riley LK, Franklin CL, Besch-Williford CL: Seroanalysis

of Tyzzer's disease in horses: implications that multiple strains

can infect Equidae. Equine Vet J 1995 Jan;27(1):8-12.

- 2. Franklin CL, Motzel SL, Besch-Williford CL, Hook RR Jr,

Riley LK: Tyzzer's infection: host specificity of Clostridium

piliforme isolates. Lab Anim Sci 1994 Dec;44(6):568-72.

- 3. Humber KA, Sweeney RW, Saik JE, Hansen TO, Morris CF:

Clinical and clinicopathologic findings in two foals infected

with Bacillus piliformis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988 Dec 1;193(11):1425-8.

- 4. Frisk CS: Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases. In: Laboratory

Hamsters, Van Hoosier GL, McPherson CW, editors, Academic Press,

Inc., pp. 121-125, 1987.

-

- International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #2456, 2934, 4195-9, 5406, 5463, 9305, 10173-4,

10927, 17147-50.

-

Case III - 97-5457 S10 (AFIP 2594500)

-

- Signalment: 18-year-old, male, castrated, Arabian

horse.

-

- History: Neurologic horse with grade 4 ataxia.

-

- Gross Pathology: In the sacral spinal canal there

was a thick, fibrous, extradural mass which formed a collar around

the sacral cord and filum terminale.

-

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Cauda equina

neuritis.

- The extradural mass seen grossly resulted from severe, diffuse,

granulomatous cauda equina neuritis where the inflammatory reaction

had become confluent. Individual nerve bundles were inflamed

and some were completely necrotic. An intense inflammatory response

was present in virtually all extradural nerve bundles, and fibrosis

and multinucleated giant cell formation added to its severity.

-

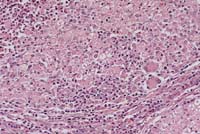

- Case 12-3. Cauda equina. The nerve bundle is replaced

by macrophages, multinucleated giant cells and a mass of neutrophils

in a necrotic area to the top left corner. The lower right shows

a mostly intact smaller nerve. 20X

AFIP Diagnosis: Cauda equina with adjacent adipose tissue:

Neuritis and ganglioneuritis, granulomatous, diffuse, severe,

with moderate chronic steatitis, Arabian horse, equine.

-

- Conference Note: Cauda equina syndrome is an uncommon

condition in horses in which the sacral and coccygeal nerves,

and occasionally cranial nerves V and VII, are chronically inflamed.

Resulting clinical signs include paralysis of the tail, rectum,

and bladder; anesthesia in the sacral dermatomes with a surrounding

zone of hyperesthesia; gluteal muscle atrophy; and hind limb

ataxia and weakness. In horses with cranial nerve involvement,

facial paralysis, head tilt, and masticatory muscle atrophy are

also seen.

- Marked granulomatous inflammation and proliferation of the

epineurial and perineurial sheaths are the major histopathologic

changes in the extradural nerve roots and spinal ganglia. Intradural

roots are usually less severely affected. Though some nerve fascicles

remain intact, many contain dense infiltrates of lymphocytes,

plasma cells, and macrophages extending into the fascicle interior.

Secondary to interruption of axons, retrograde chromatolysis

develops in the somatic motor neurons of the affected spinal

segments. Destruction of sensory neurons in the dorsal roots

and ganglia leads to orthograde nerve fiber degeneration in the

spinal dorsal funiculus.6

- The exact etiopathogenesis is unknown. Several studies have

demonstrated similarities between this condition and both the

Guillain-Barré syndrome in man and experimental allergic

neuritis (EAN) in rats. Kadlubowski and Ingram5 showed that affected

horses have circulating antibodies to P2 myelin protein, a neuritogenic

myelin antigen that on injection causes EAN. It is unclear whether

these circulating antibodies play a primary role in demyelination

or represent a consequence of antigen released in the course

of myelin destruction.6 In another study4, equine adenovirus

1 was isolated from cauda equina nervous tissue in 2 out of 3

horses with cauda equina syndrome. In 6 normal horses of similar

age, no viral agents were isolated. Though these findings suggest

a causal linkage, it is also plausible that the adenovirus infection

was established as an avirulent opportunistic infection in the

period of stress.

-

- Contributor: Oregon State University, College of Veterinary

Medicine, P.O. Box 429, Corvallis, OR 97339

-

- References:

- 1. Wright JA, Fordyce P, Edington N: Neuritis of the cauda

equina in the horse. J Comp Path 97:667-675, 1987.

- 2. Jubb KVF, Haxtable CR: The nervous system. In: Pathology

of Domestic Animals. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, and Palmer N., eds.,

Academic Press, San Diego, 4th ed., Vol. 1, p. 428, 1993.

- 3. Fordyce PS, Edington N, Bridges GC, Wright JA, Edwards

GB: Use of an ELISA in the differential diagnosis of cauda equina

neuritis and other equine neuropathies. Equine Veterinary Journal

19(1):55-59, 1987.

- 4. Edington N, Wright JA, Patel JR, Edwards GB, Griffiths

L: Equine adenovirus 1 isolated from cauda equina neuritis. Res

Vet Sci 37:252-254, 1984.

- 5. Kadlubowski M, Ingram PL: Circulating antibodies to the

neuritogenic myelin protein, P2, in neuritis of the cauda equina

of the horse. Nature 293:299-300, 24 September 1981.

- 6. Summers BA, Cummings JF, de Lahunta A: Veterinary Neuropathology,

Mosby-Year Book, Inc., St. Louis, MO, pp. 432-434, 1995.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #1588-9, 1676, 2104, 6980, 10539-43, 14179-81,

17068-72, 17115-8.

-

Case IV - 1648 or 1649 (AFIP 2600782)

- Signalment: 4-month-old, 65 kg, male, castrated, German

Landrace pig.

-

- History: To study the experimental infection with

Oesophagostomum dentatum, pigs were orally inoculated with a

single dose of 50,000 infective larvae of Oesophagostomum dentatum.

None of the animals developed clinical signs of diarrhea. The

tissues are from an animal which was euthanized at day 7 post-inoculation.

-

- Gross Pathology: Macroscopic lesions were predominantly

found in the cecum and proximal colon. The mucosa was severely

edematous and hyperemic. Numerous red and/or white nodules (1-5

mm in diameter) were visible in the mucosa.

-

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Moderate granulomatous

typhlocolitis with nematode larvae.

-

- Etiology: Oesophagostomum dentatum.

- Sections of nematode larvae are present in the lamina propria

- sometimes extending to the submucosa. Nematode larvae are surrounded

by an amorphous eosinophilic capsule which occasionally contains

neutrophils and macrophages, by a thin layer of neutrophils and

macrophages and by a thick layer of lymphocytes. Eosinophils

and mast cells are quite numerous in some parasitic nodules.

They are predominantly located in the periphery of the nodules

and in the submucosa. Tangential section through parasitic nodules

revealing only mononuclear infiltrates in the lamina propria

and submucosa are frequent. Some of them have central areas of

necrosis. The submucosa is mildly to moderately infiltrated by

lymphocytes, macrophages and eosinophils. These infiltrates extend

in some slides into the tunica muscularis and serosa.

- Sections through mucosa-associated lymphoid nodules are present

in some slides. They can be distinguished from parasitic granulomas

by the presence of lymphoid follicles which contain tingible

body macrophages and are surrounded by a collagenous capsule.

- Oesophagostomum dentatum belongs to the family Stongylidae.

It is a large intestinal nematode of pigs. Three species of Oesophagostomum

occur in pigs: O. dentatum, O. quadrispinulatum and O. brevicaudum.

Pigs become infected by oral uptake of infectious larvae. After

24 hours, these larvae penetrate the mucosa of the cecum and

proximal large intestine. They induce the formation of parasitic

granulomas in the lamina propria and submucosa. In these granulomas

they mature and return as 4th stage larvae to the intestinal

lumen between days 7 and 14 post-infection (pi). At day 14 pi,

only mild multifocal infiltrates of macrophages, lymphocytes

and eosinophils remain in the mucosa. In the intestinal lumen

the 4th stage larvae develop to adults (females: 11-15 mm, males:

8-10 mm) and start shedding eggs.

- O. dentatum has a high incidence especially in breeding pigs.

Severe infections may result in necrotizing enteritis. In most

herds, the infection is not recognized since it is frequently

subclinical. It causes, however, reduced weight gain, reduced

litter size, and may complicate other infections. Thus, it is

of economic importance. Infection with O. dentatum in pigs induces

inflammatory reactions in the intestinal mucosa, but this does

not result in protective immunity.

-

- Case 12-4. Colon. Nematode larvae (Oesophagostomum

dentatus) in the mucosa is surrounded by mononuclear leukocytes

and bordered by several crypt abscesses. 10X

- AFIP Diagnosis: Colon: Colitis, subacute and eosinophilic,

multifocal, moderate, with

- nematode larvae, German Landrace, porcine, etiology consistent

with Oesophagostomum spp.

-

- Conference Note: Oesophagostomum infection is found

world-wide. In addition to pigs, Oesophagostomum spp. are important

intestinal parasites of various ruminants and primates, including

man. In cattle, O. radiatum infection can result in severe weight

loss, anorexia, anemia and diarrhea. O. columbianum and O. venulosum

affect sheep, goats and certain wild ruminants. These species

have a similar life cycle to those affecting pigs, but the larvae

of each species infect different sections of the intestine. Adult

worms of all species are found in the cecal and colonic lumina.

-

- Oesophagostomiasis has been reported to be the most frequent

and pathogenic helminth of laboratory primates, and can represent

a serious threat to the health of colonies.2 Gross lesions include

dark nodules up to 8 mm in diameter within the submucosa or serosa

of the cecum and colon, and occasionally in the mesocolon. Incidences

of up to 70% in rhesus monkeys and 62% in cynomolgus monkeys

have been reported.

Contributor: Institut für Pathologie, Tierärztliche

Hochschule Hannover, Bünteweg 17, 30559 Hannover, Germany.

-

- References:

- 1. McCracken RM, Ross JG: The histopathology of Oesophagostomum

dentatum infections in pigs. J Comp Pathol 80:619-623, 1970.

- 2. Stewart TB, Gasbarre LC: The veterinary importance of

nodular worms (Oesophagostomum spp.). Parasitol. Today 5:209-213,

1989.

- 3. Stockdale PHG: Necrotic enteritis of pigs caused by infection

with Oesophagostomum spp. Br Vet J 126:526-529, 1970.

- 4. Abbott DP, Majeed SK: A survey of parasitic lesions in

wild-caught, laboratory-maintained primates: (rhesus, cynomolgus,

and baboon). Vet Pathol 1984 Mar;21(2):198-207.

-

- International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #5284, 13612

-

- Terrell W. Blanchard

Major, VC, USA

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: blanchard@email.afip.osd.mil

-

- * The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American

College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry

of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides

substantial support for the Registry.

-

- Return to WSC Case Menu.